Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516; doi:10.3390/ijerph17186516 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

Article

Media Reporting on Air Pollution: Health

Risk and Precautionary Measures in National and

Regional Newspapers

Steven Ramondt

1,2,

* and A. Susana Ramírez

3

1

Department of Communication Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam,

1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2

Psychological Sciences, University of California, Merced, CA 95344, USA

3

Public Health, University of California, Merced, CA 95344, USA; [email protected]

* Correspondence: s.ramondt@vu.nl

Received: 17 July 2020; Accepted: 3 September 2020; Published: 7 September 2020

Abstract: Exposure to air pollution is one of the primary global health risk factors, yet individuals lack

the knowledge to engage in individual risk mitigation and the skills to mobilize for the change

necessary to reduce such risks. News media is an important tool for influencing individual actions

and support for public policies to reduce environmental threats; thus, a lack of news coverage of such

issues may exacerbate knowledge deficits. This study examines the reporting of health risks and

precautionary measures regarding air pollution in national and regional print news. We conducted a

content analysis of two national and two local newspapers covering the USA’s most polluted region

during a 5-year period. Coders identified information on threat, self-efficacy, protective measures and

information sources. Nearly 40% of air pollution news articles mentioned human health risks. Fewer

than 10% of news stories about air pollution provided information on the precautionary measures

necessary for individuals to take action to mitigate their risk. Local newspapers did not report more

threat (Χ

2

= 1.931, p = 0.165) and efficacy (Χ

2

= 1.118, p = 0.209) information. Although air pollution

levels are high and continue to rise at alarming rates, our findings suggest that news media reporting

is not conducive to raising environmental health literacy.

Keywords: air pollution; environment health; public health; newspapers; environmental health

literacy; health promotion; health communication; efficacy; risk communication; advocacy

1. Introduction

Air pollution is the single largest environmental health risk and one of the largest global risk

factors [1,2], with outdoor air pollution estimated to be responsible for almost 8% of total global

deaths [3]. To reduce individual risk associated with air pollution, individuals need to be aware when

air quality is poor [4–6]. The primary official forms of communication about air pollution to achieve

this goal are air quality advisories; however, the information environment is much broader than

targeted campaigns [7]. The broad public information environment is an important determinant of

knowledge, attitudes, and other cognitive and emotional determinants of behavior [8–10], and should

be investigated beyond air quality advisories, especially since awareness of air quality advisories

often does not lead to behavior change, and air quality advisories are among the least reported

sources of information on air pollution [4,11]. Research has found that media, together with sensory

and health cures, are the primary sources of information in air polluted regions [11,12]. Information

found in the media can increase awareness and change perceptions of environmental risks, such as

air pollution, and help individuals with processes that lead to risk-reducing behavior [13,14].

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 2 of 10

Moreover, consistent with an ecological approach to health [2], recent research in environmental

health literacy argues that messaging must move beyond exclusively focusing on individual behavior

change to include strategies that empower individuals to mobilize for the control of environmental

exposures [15–17]. Media influences which issues the public are exposed to and thereby sets the

public agenda [18]. Agenda-setting research has furthermore shown that news coverage plays a role

in shaping public opinion and the local policy agenda, and that this role is more prominent for local-

level news [19].

The current research explores how air pollution is covered in news media in accordance with

Wardman’s [20] instrumental imperative. We examine risk communication as a resource to change

behavior in accordance with recommendations from health officials during episodes of poor air

quality [21]. To investigate how messages can change individual behavior, we utilized the extended

parallel process model (EPPM) [22]. The EPPM is commonly used to explain how individuals process

health messages, and proposes that for an individual to accept a message and change their behavior,

two appraisal steps are necessary. First, an individual needs to perceive a threat to themselves that

warrants action, and second an individual needs to perceive themselves as able to avert the threat

[22]. For an individual to rake risk-reducing action, they need to know about both the risk and

effective actions they can take to reduce risk. We therefore conducted a content analysis of

newspapers, and examined how individuals might process media messages by analyzing how much

health risk (threat) and precautionary measures (efficacy information) information air pollution

coverage contains. The effective precautionary measures individuals can take to reduce risk from

outdoor air pollution include the following: staying indoors, limiting physical activity, or using air

filters to clean indoor air during severe air pollution days [6]. However, it is important to note that

while risk reduction is desirable, complete reduction of risk is implausible. In addition, precautionary

measures can have downsides, including increasing air pollution risk. For example, some air filter

cleaners produce ozone, acerbating air pollution risk [23]. Moreover, indoor air pollution can also be

a major risk to public health, especially in developing countries [24]. In addition to examining health

risks and information about precautionary measures, we examined the potential influence of

journalists’ information sources on the framing of air pollution. The manner in which issues are

presented or framed in the media affects the perceptions of the public [25]. Media coverage of

environmental issues has been critiqued for lacking substance, adequate coverage and potential

solutions [26,27]. The choice of source for a story influences how a story is framed, the substance that

is included, and which solutions are provided [28].

National news was compared with local news from California’s San Joaquin Valley (SJV). The

SJV is a rural and economically disadvantaged region that lacks resources and access to address

environmental and public health threats [29,30]. Moreover, this region is one of the worst air polluted

areas in the US [31]. Latino, low-income and less-educated populations—which are overrepresented

in the SJV—have less access to health information [32,33]. For minorities that suffer from this lack of

access, news media is the primary and most trusted source of health information [34]. News media,

especially local news media, may be a particularly important source of information for residents of

the SJV, since the lack of resources and the geographically-dispersed nature of rural areas such as the

SJV make it hard to reach the population through other channels.

According to Ropeik and Slovic [35], effective risk communication requires more than merely

the sending of the message; factors that shape individuals’ risk perceptions should also be taken into

account. By assessing which essential risk-reducing information is missing in newspaper coverage,

and which messages individuals are exposed to, health promotion efforts can be tailored, creating

more effective campaigns. Consistent with prior content analyses of environmental risks [36,37], we

hypothesized that (1) newspapers are more likely to report information about threats to health

compared to efficacy information to reduce individual health risk. Due to the impact air pollution

has on the SJV and the concerns it raises with its residents [38,39], we expected local newspapers to

focus more on reporting about air pollution and reducing the adverse effects of air pollution.

Therefore, we hypothesize that (2) local newspapers are more likely, compared to national

newspapers, to report on the threat of air pollution to health, (3) local newspapers are more likely,

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 3 of 10

compared to national newspapers, to provide efficacy information about precautionary measures

individuals can take to reduce the risks of air pollution, and (4) local newspapers are more likely,

compared to national newspapers, to report on three precautionary outdoor air pollution measures:

staying indoors, limiting physical activity, and using air filters [6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

Two national newspapers, the New York Times and the Washington Post, were selected to

represent the national-level discourse on air pollution in the media. Two newspapers from the SJV,

the Fresno Bee and the Bakersfield Californian, represented local news about air pollution. The New

York Times and the Washington Post have high circulation and influential status and are considered

to be agenda setters for other media outlets in the US [18]. Both the Fresno Bee and the Bakersfield

Californian are among the highest circulating papers in California’s air polluted San Joaquin Valley,

and are the hometown papers of the two most polluted cities in the US [31].

2.2. News Coverage Selection

The data for this study were news stories about air pollution published in the four newspapers

during the five-year period 2011–2015. News stories were obtained from the Lexis-Nexis database for

the two national newspapers and the Newsbank World News database for the two local newspapers.

Following procedures described by Stryker and colleagues [40], a search term was constructed. News

stories about air pollution were operationalized as needing to include air pollution content in the title

and/or first three paragraphs. The following search term was used to collect the sample: ATLEAST1

(air quality or air pollution) AND (air pollution or air quality or clean air or dirty air or polluted air

or smok! or fume! or cloud or gas! or exhaust! or vapor or inhale! or breathe! or respir! or emission!

or smog or ozone) in any of the first three paragraphs (HLEAD was used in Lexis-Nexis to automate

this process). To keep our sample size manageable while obtaining an accurate estimate of the

population, a constructed week sampling approach was used. Constructed week sampling is a

stratified random sampling technique that is preferred to simple random sampling as it accounts for

variation of news content over a seven-day news week [41]. The current study sampled 6 constructed

weeks for each of the five years in which news stories (both national as well as local) were collected,

for a total of 30 constructed weeks, yielding a total of 276 articles.

2.3. Measures

We measured threat, efficacy information and information sources. All measures were

dichotomous items. Stories were coded as a threat if an article included any information about air

pollution being adverse to health. Efficacy was coded if the article included any information about

precautionary measures an individual can take to the reduce risks of air pollution. The coding of

efficacy information included an additional stage. If an article included efficacy information, the

nature of the efficacy information was investigated to see if the efficacy information included any of

the effective precautionary measures individuals can take—staying indoors, limiting physical

activity, or using air filters to clean indoor air during severe air pollution days [6]. To examine which

sources were utilized in the articles about air pollution, 5 types of sources were coded. The source

typology was based on work by Brossard and colleagues [42] and included academics and scientists,

non-expert/citizen, business/industry groups, governmental sources and health, and environmental

advocacy groups. All articles were analyzed to see if any of these sources were utilized. It was

possible to code for multiple sources per article.

Once the coding instrument was developed, two coders were randomly assigned three sections

(n = 109, 39.5% of total sample) to code. Cohen’s kappa showed substantial agreement (mean k = 0.68)

[43]. The initial interrater reliability was below the threshold set a priori (k < 0.7) for three codes

classifying cited sources: “non-expert/citizen sources”, “business/industry groups” and “health and

advocacy groups”. To achieve a higher level of reliability, the two coders double coded all articles for

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 4 of 10

these codes and conducted consensus meetings afterward. As a result, the final average Cohen’s

kappa increased to a high agreement (mean k = 0.85) [43]. The remaining years of air pollution news

articles were randomly distributed and coded independently by the two coders.

2.4. Data Analysis

To compare differences between local and national newspapers, chi-square independence tests

were conducted. A Fisher’s exact test was used in case the expected cell count was less than 5. All

descriptive statistics, reliability and chi-square tests were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0.

3. Results

A total of 276 articles met our selection criteria and were read and analyzed; this included 162

national newspaper articles and 114 local newspaper articles. The New York Times (n = 98) accounted

for the majority of the coverage, followed by the Washington Post (n = 64), the Bakersfield Californian

(n = 61) and the Fresno Bee (n = 53). There was no significant difference in the number of articles

reporting on air pollution between local and national newspapers (Χ

2

= 3.732, p = 0.053).

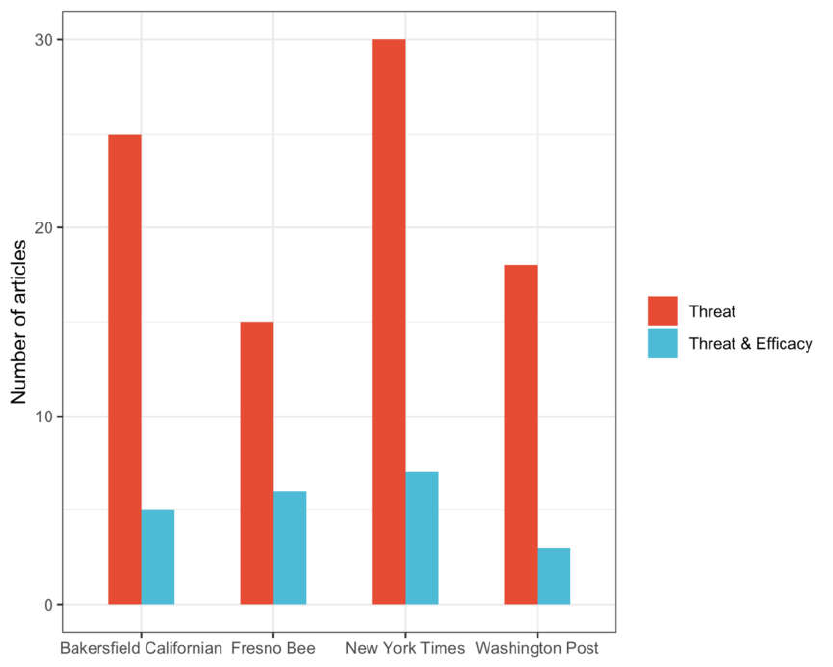

3.1. Threat and Efficacy

Threat information (39.9%) was reported more frequently than efficacy information (7.6%) in the

combined sample (Χ

2

= 34.626, p = 0.001). Threat was reported more frequently compared to efficacy

in both local newspapers (Χ

2

= 15.039, p < 0.001) and national newspapers (Χ

2

= 18.935, p < 0.001). No

newspaper reported efficacy information without reporting threat information (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Threat and efficacy information per newspaper.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 5 of 10

Table 1 compares threat and efficacy information for local and national newspapers. When

comparing local newspapers with national newspapers, local newspapers reported more threat

information (44.7%) compared to national newspapers (36.4%). However, this difference was not

statistically significant (Χ

2

= 1.931, p = 0.165). Similarly, no significant difference (Χ

2

= 1.118, p = 0.209)

was found for the reporting of efficacy information in local newspapers (13.0%) compared to national

newspapers (9.6%). When reporting recommended efficacy information, no significant differences

were found for the individual risk-reducing behaviors “stay indoors” (Χ

2

= 0.885, p = 0.347) or “use of

air filters” (Χ

2

= 0.953, p = 0.652). However, local newspapers did report more on “limiting physical

activity” compared to national newspapers (Χ

2

= 5.105, p = 0.036).

Table 1. Threat and efficacy information in news coverage of air pollution.

Total (n = 276) Local (n = 114) National (n = 162)

Threat 110 (39.9%) 51 (44.7%) 59 (36.4%)

Efficacy 21 (7.6%) 11 (9.6%) 10 (6.2%)

Stay indoors 13 (4.7%) 7 (6.1%) 6 (3.7%)

Limit physical activity * 9 (3.3%) 7 (6.1%) 2 (1.2%)

Use air filter 5 (1.8%) 1 (0.9%) 4 (2.5%)

* Significant difference in amount of efficacy information about limiting physical activity between

local and national newspapers, p < 0.05.

3.2. Information Sources

Reporters primarily used governmental sources, followed by business/industry groups, health and

environmental advocacy groups, academics and scientist, and non-expert/citizen sources (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sources utilized in local and national newspaper articles about air pollution.

A similar order was found for national newspapers. Local newspapers also used governmental

sources primarily, followed by business/industry sources and health and environmental advocacy

groups. However, they used more non-expert citizen sources compared to academic sources.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 6 of 10

National newspapers used disproportionally more information sources in their articles compared to

local newspapers. As can be seen in Table 2, national newspapers utilized significantly more

academic and scientific sources (Χ

2

= 21.881, p < 0.001), business/industry groups (Χ

2

= 28.189, p <

0.001), governmental sources (Χ

2

= 26.089, p < 0.001) and health and environmental advocacy groups

(Χ

2

= 16.680, p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in the uses of non-experts/citizens as

information sources by reporters (Χ

2

= 0.004, p = 0.950).

Table 2. Information sources cited in news coverage of air pollution.

Sources

Total (n = 276)

Local (n = 114)

National (n = 162)

Academics and scientist sources *

60

9

51

Non-expert/citizen sources

27

11

16

Business/industry groups *

79

13

66

Governmental sources *

168

49

119

Health and environmental advocacy groups *

63

12

51

Note: Each article can have multiple sources. *

Significant difference in sources utilized between local

and national newspapers, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The present study looked at the nature of air pollution reporting in the media, exploring factors

in news reporting on air pollution that might affect individual risk-reducing behavior. Similarly to

other content analyses analyzing newspaper reporting of other health issues [37,44–46], we found

that air pollution stories contained more threat information than efficacy information. It is important

that newspapers report about the threat of air pollution to health, as this informs the public on the

need for action. However, by not providing any information on what to do to reduce the introduced

threat, undesirable side effects can arise. The EPPM [22] posits that when threat information is high

and efficacy information is low, individuals will manifest a maladaptive coping response such as

denial and avoidance of information [47]. While results can differ for individuals, as individual

differences, including prior experiences, culture and personality, influence the appraisal of threat and

efficacy [22], our results suggest that current reporting about air pollution in newspapers is not

conducive to the promotion of risk-reducing behavior.

This study found that news reporting about air pollution lacked information about effective

precautionary measures that individuals can take. Local newspapers in the SJV did not report

significantly more about air pollution, threat and efficacy compared to national newspapers, despite

being located in one of the worst air polluted areas in the USA, and even though air pollution is a

major concern for residents of the valley [38,48]. The results are not entirely surprising, as the relative

absence of news stories about air pollution is in line with a recent study analyzing local news

reporting about health in the SJV, which also found limited coverage of air pollution [32]. However,

the lack of efficacy in local publications is alarming as public information sources in the region have

a similar deficiency [17], making it plausible that residents in the SJV have insufficient information

available necessary to protect themselves from the adverse effects of air pollution. Public health

advocates and health promotion experts must recognize the need to balance the structural causes of

poor air quality and the actions individuals and communities can take to reduce air pollution-related

morbidity and mortality. It is necessary to develop more effective strategies for disseminating

information about the health risks of air pollution. National and local news media outlets may be

useful partners for such dissemination, as media plays a vital role in the public understanding of

environmental risks [49].

Similar to the content analyses of other environmental issues [27,42], both local and national

newspapers over-relied on governmental sources. The high reliance on governmental sources is

concerning, as they are likely to present established views [27]. Moreover, the high reliance on

governmental sources is particularly concerning in the current political climate, as governmental

agencies are acting in conflict with their goals. For example, the agency in charge of mitigating air

pollution is advocating for relaxation of the Clean Air Act legislation [50]. The relative lack of sources

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 7 of 10

that might present unconventional views limits the range of concerns and solutions presented in the

news. This has implications for the policy changes necessary to reduce air pollution (health risk). For

instance, changes in tobacco policy benefited from the voices of diverse groups and organizations in

establishing public perceptions necessary to mobilize change. Collaboration in news media

campaigns to increase the attention the media pays to diverse voices is therefore recommended [51].

Non-governmental groups, such as health and environmental groups and academics and scientists,

should consider similar tactics to voice their concerns about air pollution. Academic and scientific

sources were present in less than a quarter of the articles. The primary reliance of air pollution

reporting on sources that might not be impartial and lack expertise might not be conductive to the

understanding of air pollution by a general audience. Future studies should investigate if these

sources cause environmental health literacy misinformation and misconceptions.

Despite its strengths, this study suffers from some limitations. To begin, only a select number of

newspapers were included in the current study. It is possible that a selection of different newspapers

would reveal different patterns. Similarly, a selection of different news sources (e.g., online news or

broadcast) could show different results. However, we are reasonably confident that this is unlikely,

because newspapers—and in particular widespread national newspapers, such as the national

newspapers (i.e., New York Times and Washington Post) utilized in this content analysis—are agenda-

setters for other media sources [9]. Our coding of threat and efficacy information used simple binary

codes. The coding therefore ignores any nuanced tones and implications that potentially exist in the

news story. Additionally, coverage patterns could have changed since the time of the study (2011–

2015), as developments, such as the WHO campaign [52] to mobilize people to bring air pollution to

safe levels, or the 2016 presidential election and resulting changes at the EPA, could have influenced

the coverage. For example, the salient new efforts made by the WHO to convince the public and

policymakers of the disastrous effects of air pollution by branding it “the silent killer” might have

increased the amount of threat reporting in newspapers. We also did not investigate weather

forecasts. Currently, weather reports can communicate threats from air pollution, but do not include

behavioral recommendations. Hence, it is possible that the negative coping effects as postulated by

the EPPM are more likely to happen. Lastly, our work analyzed air pollution communication using

a top-down approach. This risk message model perspective [20], in which the audience passively

receives information, is a simplified view of the communication process. While the message

components we examined are essential requirements for individual behavior change, future research

should take into consideration additional communication factors, including participatory

communication components, that are salient for change [21].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that reporting about air pollution in newspapers is not

conducive to risk-reducing behavior. Newspapers mostly fail to report on the health impacts air

pollution can have. Moreover, there needs to be a better balance between threat and efficacy

information—especially effective precautionary measures that individuals can take—in the reporting

about air pollution. Given the large impact air pollution has on the SJV, and the impact of local news

on public opinion and the local policy agenda, more health-promoting news stories about air

pollution would be beneficial. Health promotion efforts should consider the information in the media

environment, and develop strategies to enhance the air pollution information environment. Health

promotion efforts, such as the breath air campaign by the WHO, might mobilize people into action

by increasing the amount of threat information available. However, to neutralize potential

undesirable effects, campaigns would do well to provide efficacy information on how to reduce

individual risk associated with air pollution. The current reliance on conventional sources of

information by journalists might forestall the understanding of complex issues, such as air pollution.

Air pollution reporting would benefit from more diverse, expert and impartial sources. News

coverage of air pollution consistently misses opportunities to raise environmental health literacy.

Health promotion efforts should consider using news media strategically to increase environmental

health literacy.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 8 of 10

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, S.R. and A.S.R.; methodology, S.R. and A.S.R.; software, S.R.; formal

analysis, S.R.; writing—original draft, S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R. and A.S.R.; visualization, S.R.;

supervision, A.S.R.; funding acquisition, A.S.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of

the manuscript.

Funding: A.S.R. was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants P30DK092924 and

K01CA190659

Acknowledgments: We thank J. Wallander and A.V. Song for their expert advice. We thank Nadia Alazzeh,

Jacqueline Diaz, Kimberly Huynh, Natalie Pena Marquez and Yesenia Villa for their coding efforts.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the

study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to

publish the results.

References

1. Forouzanfar, M.H.; Alexander, L.; Anderson, H.R.; Bachman, V.F.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.;

Casey, D.; Coates, M.M.; Cohen, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79

behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries,

1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 2287–2323,

doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00128-2.

2. Owiti, P.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.; Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly,

S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512,

doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32345-0.

3. WHO. Mortality and Burden of Disease from Ambient Air Pollution. Available online:

https://www.who.int/gho/phe/outdoor_air_pollution/burden/en/(accessed on 17 July 2020).

4. Borbet, T.C.; Gladson, L.A.; Cromar, K.R. Assessing air quality index awareness and use in Mexico City.

BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 538, doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5418-5.

5. Cairncross, E.K.; John, J.; Zunckel, M. A novel air pollution index based on the relative risk of daily

mortality associated with short-term exposure to common air pollutants. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 8442–

8454, doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.07.003.

6. Laumbach, R.; Meng, Q.; Kipen, H.M. What can individuals do to reduce personal health risks from air

pollution? J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 96–107.

7. Moldovan-Johnson, M.; Tan, A.S.; Hornik, R. Navigating the cancer information environment: The

reciprocal relationship between patient-clinician information engagement and information seeking from

nonmedical sources. Heal. Commun. 2013, 29, 974–983, doi:10.1080/10410236.2013.822770.

8. Leask, J.; Hooker, C.; King, C. Media coverage of health issues and how to work more effectively with

journalists: A qualitative study. BMC Public Heal. 2010, 10, 535, doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-535.

9. Niederdeppe, J.; Frosch, D.L.; Hornik, R. Cancer News Coverage and Information Seeking. J. Heal. Commun.

2008, 13, 181–199, doi:10.1080/10810730701854110.

10. Viswanath, K. The communications revolution and cancer control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 828–835,

doi:10.1038/nrc1718.

11. Brown, P.; Cameron, L.D.; Cisneros, R.; Cox, R.; Gaab, E.; Gonzalez, M.; Ramondt, S.; Song, A. Latino and

Non-Latino Perceptions of the Air Quality in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal.

2016, 13, 1242, doi:10.3390/ijerph13121242.

12. Johnson, B.B. Experience with Urban Air Pollution in Paterson, New Jersey and Implications for Air

Pollution Communication. Risk Anal. 2011, 32, 39–53, doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01669.x.

13. Mello, S. Media Coverage of Toxic Risks: A Content Analysis of Pediatric Environmental Health

Information Available to New and Expecting Mothers. Heal. Commun. 2015, 30, 1–11,

doi:10.1080/10410236.2014.930398.

14. Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285, doi:10.1126/science.3563507.

15. Finn, S.; O’Fallon, L. The Emergence of Environmental Health Literacy—From Its Roots to Its Future

Potential. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2015, 125, 495–501, doi:10.1289/ehp.1409337.

16. Gray, K.M. From Content Knowledge to Community Change: A Review of Representations of

Environmental Health Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 466, doi:10.3390/ijerph15030466.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 9 of 10

17. Ramírez, A.S.; Ramondt, S.; Van Bogart, K.; Perez-Zuniga, R. Public Awareness of Air Pollution and Health

Threats: Challenges and Opportunities for Communication Strategies to Improve Environmental Health

Literacy. J. Heal. Commun. 2019, 24, 75–83, doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1574320.

18. McCombs, M.E. Setting the Agenda: The Mass Media and Public Opinion; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004.

19. Nagler, R.H.; Bigman, C.A.; Ramanadhan, S.; Ramamurthi, D.; Viswanath, K. Prevalence and Framing of

Health Disparities in Local Print News: Implications for Multilevel Interventions to Address Cancer

Inequalities. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 603–612, doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1247.

20. Wardman, J.K. The Constitution of Risk Communication in Advanced Liberal Societies. Risk Anal. 2008, 28,

1619–1637, doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01108.x.

21. Signorino, G.; Beck, E. Risk Perception Survey in Two High-Risk Areas. In Human Health in Areas with

Industrial Contamination; Mudu, P., Terracini, B., Martuzzi, M., Eds.; World Health Organization—Europe:

Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014; pp. 232–245.

22. Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun. Monogr.

1992, 59, 329–349, doi:10.1080/03637759209376276.

23. Salonen, H.; Salthammer, T.; Morawska, L. Human exposure to ozone in school and office indoor

environments. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 503–514, doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.012.

24. Bruce, N.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Albalak, R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: A major

environmental and public health challenge. Bull. World Heal. Organ. 2000, 78, 1078–1092.

25. Scheufele, D.A.; Shanahan, J.; Kim, S.-H. Who Cares about Local Politics? Media Influences on Local

Political Involvement, Issue Awareness, and Attitude Strength. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2002, 79, 427–444,

doi:10.1177/107769900207900211.

26. Boykoff, M.T.; Boykoff, J.M. Climate change and journalistic norms: A case-study of US mass-media

coverage. Geoforum 2007, 38, 1190–1204, doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008.

27. Zamith, R.; Pinto, J.; Villar, M.E. Constructing Climate Change in the Americas. Sci. Commun. 2012, 35, 334–

357, doi:10.1177/1075547012457470.

28. Liebler, C.M.; Bendix, J. Old-Growth Forests on Network News: News Sources and the Framing of An

Environmental Controversy. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1996, 73, 53–65, doi:10.1177/107769909607300106.

29. Abood, M. San Joaquin Valley Fair Housing and Equity Assessment. Available online:

http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/SJV-Fair-Housing-and-Equity-Assessment.pdf

(accessed on 4 December 2016).

30. Taylor, J.E.; Martin, P.L. The new rural poverty: Central Valley evolving into patchwork of poverty and

prosperity. Calif. Agric. 2000, 54, 26–32, doi:10.3733/ca.v054n01p26.

31. American Lung Association. State of the air State of the Air 2019. In State of the Air; American Lung

Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019.

32. Ramírez, A.S.; Estrada, E.; Ruiz, A. Mapping the Health Information Landscape in a Rural, Culturally

Diverse Region: Implications for Interventions to Reduce Information Inequality. J. Prim. Prev. 2017, 38,

345–362, doi:10.1007/s10935-017-0466-7.

33. Viswanath, K.; Ackerson, L.K. Race, Ethnicity, Language, Social Class, and Health Communication

Inequalities: A Nationally-Representative Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14550,

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014550.

34. Hispanics and Healthcare in the United States: Access, Information and Knowledge. Available online:

https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2008/08/13/hispanics-and-health-care-in-the-united-states-access-

information-and-knowledge/(accessed on 25 August 2020).

35. Ropeik, D.; Slovic, P. Risk Communications: A Neglected Tool in Protecting Public Health. Risk Perspect.

2003, 11, 4.

36. Feldman, L.; Hart, P.S.; Milosevic, T. Polarizing news? Representations of threat and efficacy in leading US

newspapers’ coverage of climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 2015, 26, 481–497,

doi:10.1177/0963662515595348.

37. Hart, P.S.; Feldman, L. Threat without Efficacy? Climate Change on U.S. Network News. Sci. Commun. 2014,

36, 325–351, doi:10.1177/1075547013520239.

38. Cisneros, R.; Brown, P.; Cameron, L.; Gaab, E.; Gonzalez, M.; Ramondt, S.; Veloz, D.; Song, A.; Schweizer,

D. Understanding Public Views about Air Quality and Air Pollution Sources in the San Joaquin Valley,

California. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2017, 2017, 1–7, doi:10.1155/2017/4535142.

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6516 10 of 10

39. Hall, J.V.; Brajer, V.; Lurmann, F.W. Measuring the gains from improved air quality in the San Joaquin

Valley. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 1003–1015, doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.05.002.

40. Stryker, J.E.; Wray, R.J.; Hornik, R.; Yanovitzky, I. Validation of Database Search Terms for Content

Analysis: The Case of Cancer News Coverage. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2006, 83, 413–430,

doi:10.1177/107769900608300212.

41. Luke, D.; Caburnay, C.A.; Cohen, E.L. How Much Is Enough? New Recommendations for Using

Constructed Week Sampling in Newspaper Content Analysis of Health Stories. Commun. Methods Meas.

2011, 5, 76–91, doi:10.1080/19312458.2010.547823.

42. Brossard, D.; Shanahan, J.; McComas, K. Are Issue-Cycles Culturally Constructed? A Comparison of French

and American Coverage of Global Climate Change. Mass Commun. Soc. 2004, 7, 359–377,

doi:10.1207/s15327825mcs0703_6.

43. Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017.

44. He, S.; Shen, Q.; Yin, X.; Xu, L.; Lan, X. Newspaper coverage of tobacco issues: An analysis of print news

in Chinese cities, 2008–2011. Tob. Control. 2013, 23, 345–352, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050545.

45. Jensen, J.D.; Moriarty, C.M.; Hurley, R.J.; Stryker, J.E. Making Sense of Cancer News Coverage Trends: A

Comparison of Three Comprehensive Content Analyses. J. Heal. Commun. 2010, 15, 136–151,

doi:10.1080/10810730903528025.

46. Shim, M.; Kim, Y.; Kye, S.Y.; Park, K. News Portrayal of Cancer: Content Analysis of Threat and Efficacy

by Cancer Type and Comparison with Incidence and Mortality in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2016, 31, 1231–

1238, doi:10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1231.

47. Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns.

Heal. Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615, doi:10.1177/109019810002700506.

48. Meng, Y.-Y.; Rull, R.; Wilhelm, M.; Lombardi, C.; Balmes, J.; Ritz, B. Outdoor air pollution and uncontrolled

asthma in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. 2010, 64, 142–147,

doi:10.1136/jech.2009.083576.

49. Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Yost, J.; Ciliska, D.; Krishnaratne, S. Communication about environmental health

risks: A systematic review. Environ. Heal. 2010, 9, 67, doi:10.1186/1476-069x-9-67.

50. Tabuchi, H. Calling Car Pollution Standards ‘Too High,’ E.P.A. Sets Up Fight with California. The New York

Times, 2018.

51. Eliott, J.; Forster, A.J.; McDonough, J.; Bowd, K.; Crabb, S. An examination of Australian newspaper

coverage of the link between alcohol and cancer 2005 to 2013. BMC Public Heal. 2017, 18, 47,

doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4569-0.

52. BreatheLife. Available online: http://breathelife2030.org/(accessed on 17 April 2018).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).