EDITED BY

Eva Unternaehrer,

University Psychiatric Clinic Basel, Switzerland

REVIEWED BY

Roma Jusiene,

Vilnius University, Lithuania

Katherine Cost,

McMaster University, Canada

*

CORRESPONDENCE

V. Konok

RECEIVED 11 August 2023

ACCEPTED 13 May 2024

PUBLISHED 28 June 2024

CITATION

Konok V, Binet M-A, Korom Á, Pogány Á,

Miklósi Á and Fitzpatrick C (2024) Cure for

tantrums? Longitudinal associations between

parental digital emotion regulation and

children’s self-regulatory skills.

Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 3:1276154.

doi: 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

COPYRIGHT

© 2024 Konok, Binet, Korom, Pogány, Miklósi

and Fitzpatrick. This is an open-access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The

use, distribution or reproduction in other

forums is permitted, provided the original

author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are

credited and that the original publication in

this journal is cited, in accordance with

accepted academic practice. No use,

distribution or reproduction is permitted

which does not comply with these terms.

Cure for tantrums? Longitudinal

associations between parental

digital emotion regulation and

children’s self-regulatory skills

V. Konok

1

*

, M.-A. Binet

2

, Á. Korom

3

, Á. Pogány

1

, Á. Miklósi

1,4

and

C. Fitzpatrick

5

1

Department of Ethology, Faculty of Science, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary,

2

Faculty of

Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada,

3

Faculty of Science,

Doctoral School of Biology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary,

4

ELKH-ELTE Comparative

Ethology Research Group, Budapest, Hungary,

5

Faculty of Education, Université de Sherbrooke,

Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

Introduction: Parents often use digital devices to regulate their children’s

negative emotions, e.g., to stop tantrums. However, this could hinder child

development of self-regulatory skills. The objective of the study was to

observe bidirectional longitudinal associations between parents’ reliance on

digital devices to regulate their child’s emotions and self-regulatory tendencies

(anger/frustration management, effortful control, impulsivity).

Methods: Parents (N = 265) filled out the Child Behavior Questionnaire—Short

Form and the Media Assessment Questionnaire twice: the initial assessment

(T1) took place in 2020 (mean child age = 3.5 years old), and follow-up (T2)

occurred a year later in 2021 (mean child age = 4.5 years old).

Results: Higher occurrence of parental digital emotion regulation (PDER) in T1

predicts higher anger and lower effortful control in T2, but not impulsivity.

Higher anger in T1, but not impulsivity and effortful control, predicts higher

PDER in T2.

Discussion: Our results suggest that parents of children with greater

temperament-based anger use digital devices to regulate the child’s emotions

(e.g., anger). However, this strategy hinders development of self-regulatory

skills, leading to poorer effortful control and anger management in the child.

KEYWORDS

emotion regulation, self-regulation, digital devices, longitudinal, effortful control,

impulsivity

1 Introduction

Digital device use among young children is markedly increasing. Children are

introduced to screens at earlier and earlier developmental stages (1). Screen-based

activities occupy the largest part of children’s free time, compared to outdoor play or

other screen-free activities (2). Pre-pandemic studies report that preschoolers spend

about 1.5–2.5 h in front of a screen daily (3, 4), and this amount has increased by one

hour during the pandemic (5). The proportion of families that possess mobile devices

has increased from 52% in 2011 to 98% in 2020 and almost half of 2- to 4-years-olds

have their own mobile device (6). About 26% of children aged 0–4 from the United

States spend more than 4 h in front of a screen daily, meaning a two-fold increase

compared to 13% before the pandemic (7). Despite these tendencies the effects of

TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 28 June 2024

|

DOI 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 01 frontiersin.org

screen time on child emotional and cognitive development are still

debated and largely unknown (8). The widespread usage of

electronic media and digital devices (TV, videogames, PC,

smartphones, tablets, etc.) may influence even adults’ cognition,

emotions, and mental health (9, 10). However, young children’s

brain and cognitive processes are still plastic, making them even

more potentially vulnerable to strong and long-lasting influences

of experiences (11–13).

Early childhood is a critical time for learning basic self-

regulation skills (14). Self-regulation is conceptualized as the

organization or modulation of affective, mental, and behavioral

responses, including control over emotional experiences and

expressions (i.e., emotion regulation), cognitive processes

(i.e., executive function), and approach or withdrawal behaviors

(i.e., effortful control) (15). Executive function and effortful

control are related and, according to some researchers,

overlapping constructs (16, 17). Effortful control has been

defined as children’s ability to inhibit a dominant response in

favor of a subdominant one, or an automatic response in favor

of a deliberate one (18, 19). It involves the management of

attention or behavior. Effortful control is temperamentally based,

but also develops with considerable input from the environment

(19) especially through children’s early social relationships with

their parents (20, 21).

Emotion regulation involves implicit or explicit attempts to

modify the natural trajectory of one or more parameters of

emotion (22), including physiological arousal, expression,

intensity or duration. It is related to temperamental emotional

reactivity [high reactivity hinders its effectiveness (23);], and to

coping [i.e., the ability to cope with the stressful situation

(24, 25)]. Emotion regulation emerges in rudimentary forms in

infancy (26), and gradually progresses from being a highly

external process to an internal one over time (25). Certain early

childhood experiences, e.g., appropriate family interactions are

necessary for this developmental process (27).

In the past decades, digital devices have become increasingly

prevalent in people’s lives and became objects with which

emotions, cognition, and behavior can be regulated. Therefore,

devices and screen-based activities have become external tools of

self-regulation. For example, digital activities (e.g., videogaming,

watching videos, instant messaging) often serve an emotion-

regulating purpose in adults [“digital emotion regulation

”;(28);

for a review: (29)]. They help in coping with or recovery from

negative emotions and stress by providing a sense of mastery and

control (29, 30), an immersive or “flow” experience (31–33), and

by providing a distraction from real-life problems or escape from

reality into the virtual world (34). Digital activities offer instant

rewards (35, 36) which can modulate one’ s mood and emotions.

Digital activities can also help in arousal-regulation for

individuals with lower arousal by offering stimulation through

e.g., fast-paced, intensive, simultaneous stimuli (8, 37)or

arousing (e.g., violent) contents, which activate the dopamine

and the reward pathways (8).

Parents often give digital devices to their child to “safely”

engage them (“baby-sitter” function), and to regulate their

emotions or behavior (38–40). Kabali et al. (41) found that 65%

of parents use mobile devices to keep their child calm in public

places. Television is also commonly used as a calming tool for

children (42, 43). We refer to this phenomenon as parental

digital emotion regulation (PDER), designating parental

behaviors such as giving the child a digital device to regulate

their negative emotions or calm them down.

Providing children with digital devices as “digital pacifiers” (41)

may reduce child emotional expressions in the short term and may

help parents allocate resources to necessary tasks and provide them

with free time, especially during lockdown (44). However, this

practice may also lead to missed opportunities to teach adaptive

emotion regulation and coping strategies to the child (45).

Although the distraction of attention away from stressful stimuli

or negative emotions can be an effective short-term strategy to

reduce emotional intensity in young children (46), suppressing

emotions can have paradoxical, rebounding effects [e.g., (47)],

and it may lead to maladaptive, avoidant coping strategies,

increased negative emotionality or dysregulation in the future.

Additionally, for children with immature self-regulatory skills, it

may be harmful to become accustomed to external devices to

regulate their emotions, as this could interfere with the

development of internal regulatory mechanisms. Dependence on

the device may lead to problematic media use and “screen time

tantrums” (48), i.e., extreme emotions when media is removed

(40). In addition, when digital devices are used for getting

instant rewards (35, 36), it may hinder one’s ability to delay

gratification and control impulses (49, 50). This may lead to a

positive feedback loop. As a consequence, an association is

frequently found between media use and impulsivity (51–53)or

poorer executive functions (54–57).

Empirical evidence suggests a negative association between

digital media use and self-regulation. For example, more time

spent watching TV was associated with higher ratings on

negative emotionality, emotional reactivity, aggression, and

attention problems, as well as lower levels of soothability in

toddlers (58). Children who began using screen media devices

earlier or who spent more time engaging with mobile devices

displayed lower self-regulation (59). Longitudinal data mainly

suggest bidirectional relationships. For example, screen time or

digital media use at a younger age was negatively associated with

later child self-regulation or related processes, such as executive

function and effortful control (37, 55, 57, 60–62). However,

findings also support the reverse association: emotion

dysregulation and poor self-regulation was found to contribute to

greater and more problematic media use later (37, 42, 63, 64).

However, whether bidirectional associations exist between the use

of PDER and child self-regulation remains unknown.

The few studies investigating PDER suggest its potential role in

child self-regulatory skills development. Coyne et al. (40) found that

temperamental dysregulation risk factors, specifically negative

affectivity and surgency (65, 66), were related to problematic

media use and screen time tantrums through PDER. This

suggests that difficult temperament (entailing low self-regulation

skills) leads to PDER, which, in turn, leads to problematic media

use. In line with this, children with social-emotional difficulties,

poor self-regulation and a difficult temperament have a higher

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 02 frontiersin.org

chance of being given digital technology as a calming tool or as a

baby-sitter (39, 42, 43, 67, 68) and perhaps as a result, they use

more media later (37, 62, 64, 69).

However, as far as we know, only one longitudinal study (69)

investigated the bidirectional associations between PDER and

child self-regulation. This study found an interaction effect:

PDER in an earlier time point (T1) was positively related to

increases in children’s negative emotionality in a later time point

(T2), but only for children with initially low negative

emotionality. Further longitudinal studies are needed as the

above-mentioned results are not in line with the frequently

found bidirectional association between media use and self-

regulation. Therefore, the objective of the study was to observe

bidirectional longitudinal associations between PDER and child

self-regulatory tendencies (anger/frustration management,

effortful control, impulsivity). Since self-regulatory skills are still

immature in the preschool age, PDER can have a great impact

on them. Therefore, we aimed to investigate this age group. We

also accounted for the confounding effects of parenting stress,

child screen time, and family sociodemographics.

This is a confirmatory study with clear hypotheses: we expect

that poorer child self-regulatory tendencies (i.e., higher level of

anger/frustration management problems, impulsivity and lower

level of effortful control) (at T1) lead to higher PDER (at T2), and

that higher PDER (at T1) leads to poorer child self-regulatory

tendencies (higher anger/frustration management problems and

impulsivity, and lower level of effortful control) (at T2).

2 Materials and method

2.1 Procedure and participants

This study is part of a larger, two-year longitudinal study on

digital media use by Canadian families with preschool children

aged 2–5 years during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participating

families were recruited using eye-catching posters and flyers in

preschools and pre-kindergarten classes, sign-up sheets and

presentations given at preschool and pre-kindergarten

registration nights, a Facebook page, and newspaper and radio

advertisements broadcast across Nova Scotia (Canada). To

measure bidirectional associations between parental digital

emotion regulation and child self-regulation tendencies, we

measured these variables at two time points.

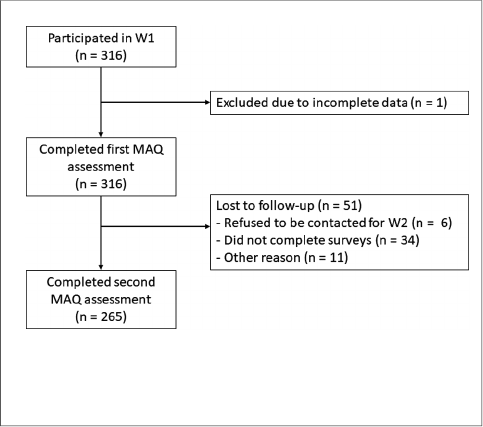

The first assessment took place between March and August of

2020 (N = 316 children), during a provincially declared state of

emergency and lockdown. A follow-up with this sample was

conducted a year later, between April and August of 2021 (N = 265;

a flow diagram of the participants is presented in Figure 1).

Demographics for the retested sample are presented in Table 1.

At both time waves, parents completed the web-based Media

Assessment Questionnaire (MAQ), which has been described in

detail elsewhere (70). The MAQ assesses child and parent media

use and includes questions on child age and sex, parent

education, as well as reasons reported by parents to allow their

child to use media. For the purpose of this study, we integrated

items on child temperamental anger/frustration, impulsivity and

effortful control using the Child Behavior Questionnaire—Short

Form (71). We also integrated items on parenting stress using

the Parenting Stress Index (72). These measures are described

below. The use of data for this specific study received approval

from the ethics board from the principal investigator’s institution

(IRB #2021-2927). Informed consent to participate was obtained

from participating parents.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Parental digital emotion regulation (PDER)

Parents were asked to rate how much they agreed or disagreed

with the statement “I let my child use media to calm them down

when they are upset”. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert

scale ranging from Never (1) to Several times per day (7). Due to

some of the response options having very small frequencies (e.g.,

“Several times per day”: N = 4), this variable was then recoded

into a dichotomous variable (1 = Never/rarely, 2 = Regularly/

frequently; see Table 1 for descriptives).

2.2.2 Child self-regulatory tendencies

The Child Behavior Questionnaire—Short form (71) assesses

several distinct dimensions of temperament which are grouped

into three main factors: negative affectivity, surgency/

extraversion, and effortful control. The short form shows

satisfactory internal consistency, criterion validity, longitudinal

stability and inter-rater agreement (71, 73). Since we focus on

temperament-based self-regulatory tendencies, we retained for

this study (1) anger/frustration (“anger” hereinafter) which is a

dimension belonging to the negative affectivity main factor, (2)

impulsivity which is a dimension belonging to the surgency/

extraversion main factor, and finally (3) the main factor of

effortful control. Anger (e.g., “Child gets angry when told s/he

has to go to bed”) and impulsivity (e.g., “Usually rushes into an

activity without thinking about it”) were each based on the mean

FIGURE 1

Flow diagram showing the number of participants contacted, lost for

specific reasons and retained.

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 03 frontiersin.org

of 6 items. Higher scores in anger and impulsivity subscales

indicate greater intensity and duration of the child’s angry or

frustrated response to environmental stimuli or greater speed of

response initiation, respectively. The effortful control factor was

based on mean scores obtained for the dimensions of attentional

focusing (six items, e.g., “When drawing or coloring a book,

shows strong concentration”) and inhibitory control (six items,

e.g., “Can wait before entering into new activities if s/he is asked

to”). Higher scores in the attentional focusing and the inhibitory

control subscales indicate better child effortful control. Items are

scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely

untrue of your child) to 7 (extremely true of your child). The

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for anger, impulsivity, and effortful

control in Wave 1 were α = 0.789; 0.629 and 0.792, respectively.

In Wave 2, the corresponding coefficients were α = 0.814; 0.656

and 0.785, respectively (see Table 1 for descriptives).

2.2.3 Demographics, parenting stress and child

screen time

When completing the MAQ (70), parents reported child age

and sex (assigned at birth), parent age and sex, parent education,

yearly income, race, country of birth, marital status, and

parenting stress. Race, country of birth and marital status were

not used in the analyses because there was little variance on

these variables (see Table 1 for response options and number/

percentage of participants answering them). Parenting stress was

assessed using the Parenting Stress Index (72). This questionnaire

includes a Parental distress (PD) subscale (12 items, i.e., “I find

myself giving up more of my life to meet my child’s needs than I

ever expected”) and a Parent-child dysfunctional interaction

(PCDI) subscale (12 items, i.e., “My child smiles at me much less

than I expected”). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale as:

1 (strongly disagree); 2 (disagree); 3 (not sure); 4 (agree) or 5

(strongly agree) and were then averaged to create a total score

ranging from 1 to 5, with an adequate internal consistency

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.850). Higher scores indicate higher

parenting stress (see Table 1 for descriptives).

In the MAQ, parents also reported their child screen time by

reporting the average amount of time their child spent doing

each of the following activities: (1) Watching TV or DVDs; (2)

Using a computer; (3) Playing video games on a console; (4);

Using an iPad, tablet, LeapPad, iTouch, or similar mobile device

(excluding smartphones); or (5) Using a smartphone. For each

activity, response options were: (1) Never; (2) Less than 30 min;

(3) 30 min to 1 h; (4) 1–2 h; (5) 2–3 h; (6) 3–4 h; (7) 4–5 h; and

(7) more than 5 h. Parents reported this separately for a typical

weekday and a typical weekend day. Total amount of child

screen time was calculated by summing the durations for each

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics of the final sample (N = 265).

Variable Measure N (%) M ± SD (Min, Max)

Child age T1 In years N (%) missing = 1 (0.4) 3.46 ± 0.84 (2, 5.42)

Child age T2 In years N (%) missing = 0 4.33 ± 0.86 (2.75, 6.33)

Child sex (2 values) N (%) boys = 138 (52.1) N (%) girls = 126 (47.5) N (%) missing = 1 (0.4)

Parent age T1 In years N (%) missing = 0 (0) 35.24 ± 4.28 (23, 52)

Parent age T2 In years N (%) missing = 0 (0) 36.24 ± 4.28 (24, 53)

Parent sex (2 values) N (%) males = 20 (7.5) N (%) females = 245 (92.5) N (%) missing = 0 (0)

Parental education (3 values) N (%) college or secondary degree = 62 (23.4)

N (%) bachelor’s degree = 129 (48.7)

N (%) master or doctoral degree = 74 (27.9) N (%) missing = 0 (0)

Yearly income (3 values) N (%) $59,999 and less = 40 (15.1)

N (%) 60,000–$99,999 = 72 (27.2)

N (%) $100,000 and more = 136 (51.3) N (%) missing = 17 (6.4)

Race (7 values) N (%) Aboriginal = 2 (0.8) N (%) Asian = 5 (1.9) N (%) Black = 2 (0.8) N (%) White = 242 (91.3)

N% Don’t know = 0 (0) N (%) Prefer not to answer = 1 (0.4) N (%) Other = 12 (4.5) N (%)

missing = 1 (0.4)

Country of birth (2 values) N (%) Canada (country) = 239 (90.2) N (%) Other = 25 (9.4) N (%) missing = 1 (0.4)

Marital status (6 values) N (%) Married = 218 (82.3) N (%) Single/Never married = 11 (4.2) N (%) Live-in partner = 28

(10.6) N (%) Divorced = 2 (0.8) N (%) Widowed = 0 (0) N (%) Separated = 5 (1.) N (%)

missing = 1 (0.4)

Child screen time T1 In hours/day N (%) missing = 0 (0) 3.45 ± 2.45 (0, 10.43)

Child screen time T2 In hours/day N

(%) missing = 0 (0) 3.26 ± 2.38 (0, 9.65)

Parenting stress T1 (total score 0–5) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 1.85 ± 0.53 (1, 3.76)

Parenting stress T2 (total score 0–5) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 1.14 ± 0.72 (0, 3.11)

CBQ anger T1 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.25 ± 1.11 (1, 7)

CBQ anger T2 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.26 ± 1.15 (1, 6.67)

CBQ impulsivity T1 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.43 ± 0.93 (1.67, 7)

CBQ impulsivity T2 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.19 ± 0.94 (1.33, 6.83)

CBQ effortful control T1 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.71 ± 0.82 (2.58, 6.83)

CBQ effortful control T2 (total score 0–7) N (%) missing = 0 (0) 4.88 ± 0.82 (2.75, 7)

Parental digital emotion

regulation T1

(after merging:

2 values)

N (%) never/rarely = 165 (62.3) N (%) regularly/frequently = 100 (37.7) N (%) missing = 0 (0)

Parental digital emotion

regulation T2

(after merging:

2 values)

N (%) never/rarely = 179 (67.5) N (%) regularly/frequently = 86 (32.5) N (%) missing = 0 (0)

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 04 frontiersin.org

activity, using responses’ mid-points with the exception of “Never”

and “more than 5 h” where scores of 0 and 5 were used,

respectively. To compute child average daily screen time, we

computed a weighted average of screen time across the week as

follows: [(weekday screen time X 5) + (weekend screen time X

2)]/7 (see Table 1 for descriptives).

2.3 Data analytic strategy

First, we compared whether retained (those who participated at

T2) and unretained (those who had dropped out) participants were

different in any aspects of demographics, parental digital emotion

regulation (PDER), or child self-regulation scores (Mann–Whitney

tests, t-tests and χ

2

tests, using SPSS 28.0.0.0).

Of the final retained sample of 265, 17 participants had a

missing value on income and one participant had a missing

value for child anger, impulsivity, and effortful control at T2. We

performed Little’s test to determine if data were missing

completely at random (MCAR). The test was not significant

revealing that data could be assumed to be MCAR: χ

2

= 24.476,

DF = 26, p = 0.549.

We imputed missing values on income to the median (value

of 3) and u sed FIML (maximum likelihood in for mation) to

account for missing outcome data.

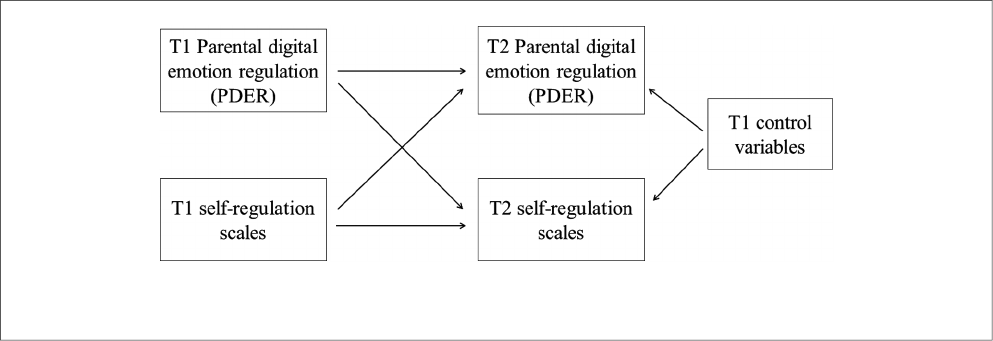

To test bidirectional associations between PDER and self-

regulation scales, we estimated cross-lagged panel models using

Mplus version 8.10 (74). We controlled for sociodemographic

variables such as child age and sex, parent age and sex, parent

education, yearly income, child screen time and parenting stress

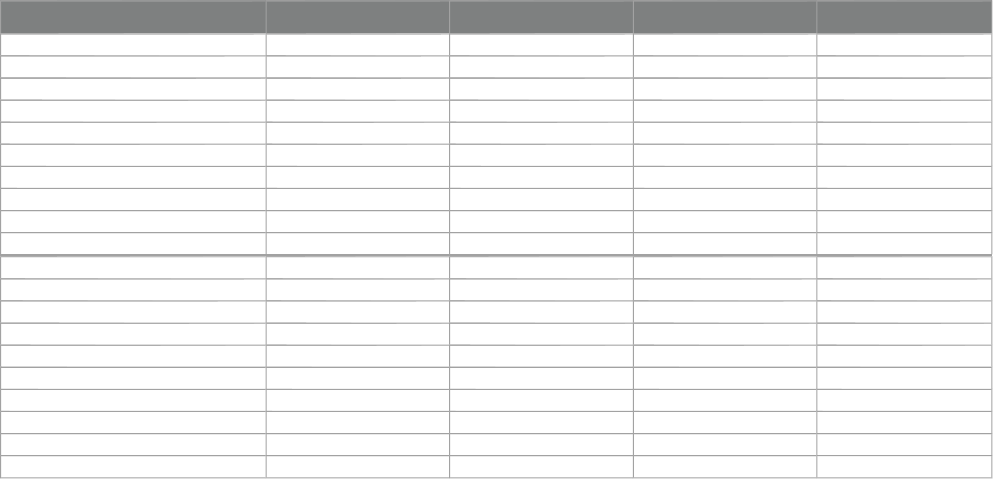

(the model schema is presented on Figure 2).

3 Results

3.1 Comparing retained and unretained

participants

Unretained participants were significantly different from

retained participants in parents’ age (M ± SD = 33.32 ± 4.631

(unretained) vs. 35.226 ± 4.278 years (retained); t = 2.852; p = 0.005;

Cohen’s d = 0.436) and marginally in PDER (52% vs. 37.6% of

regular/frequent PDER in unretained and retained sample,

respectively; χ

2

= 3.643; p = 0.056; this is discussed in the limitation

section), but was not significantly different on any other

demographic variables or child behavior variables (all p > 0.170).

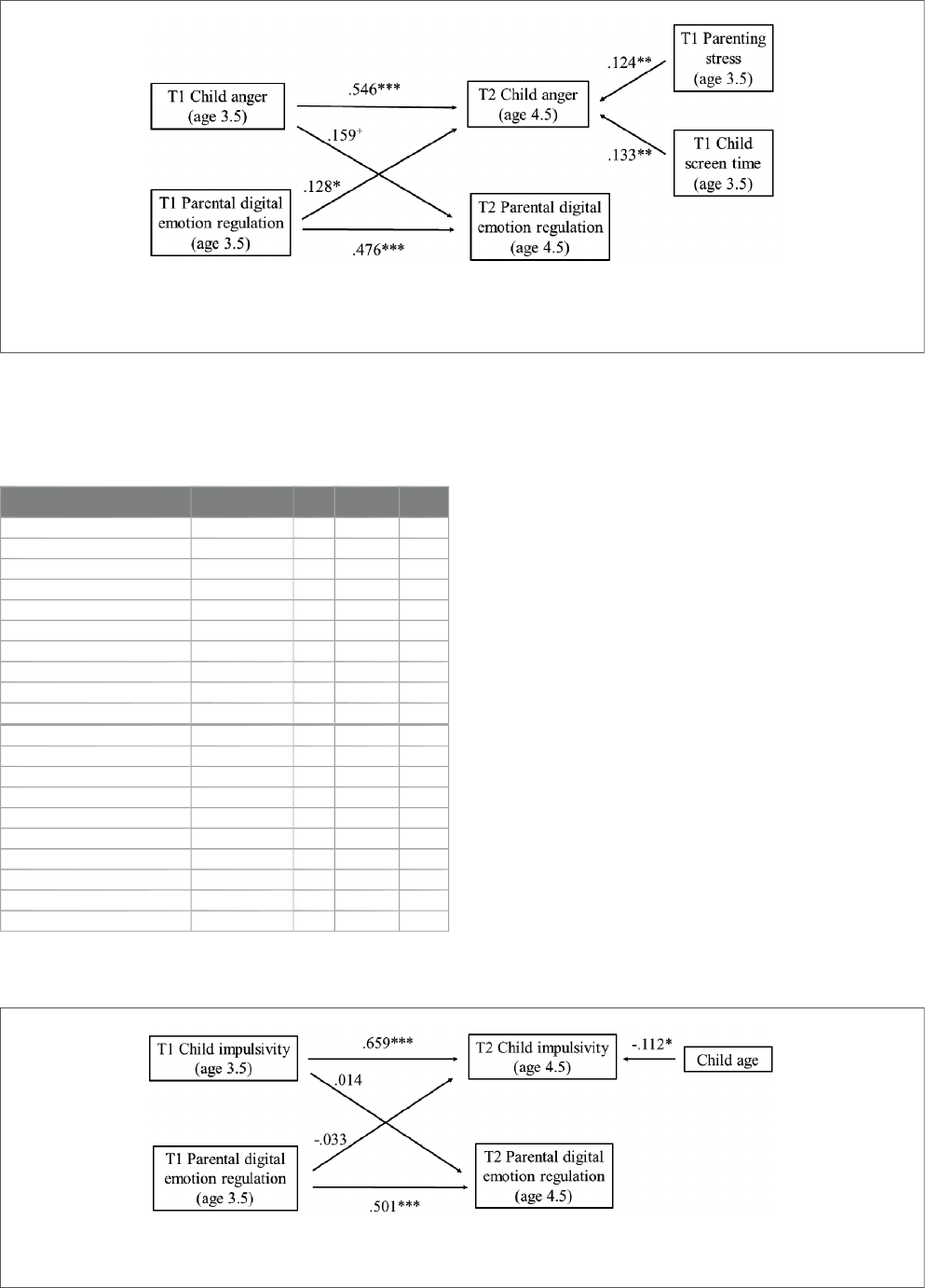

3.2 Cross-lagged panel model: anger

Our final model is presented in Figure 3. Our cross-lagged

panel model provided good fit [CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA

= 0.000 (0.000; 0.138)] and accounted for 36.7% and 45.8% of

the variance in PDER and Anger at T2, respectively. Analyses

revealed considerable stability in PDER (b = 1.233; SE = 0.187;

p < 0.001; β = 0.476) and Anger (b = 0.567; SE = 0.054; p < 0.001;

β = 0.546) between T1 and T2. In terms of the cross-lagged

associations, T1 PDER significantly contributed to higher Anger

at T2 (b = 0.304; SE = 0.122; p = 0.013; β = 0.128), whereas T1

Anger only tendentiously contributed to higher PDER at T2

(b = 0.180; SE = 0.1 08; p =0.094; β = 0.159). Parenting stress

(b = 0.018; SE = 0.007; p = 0.008; β = 0.124) and child s creen

time (b = 0.063; SE = 0.024; p = 0.009; β = 0.133) at T1 were also

significantly positively associated with Anger at T2 (Table 2).

3.3 Cross-lagged panel model: impulsivity

Our model is presented in Figure 4. Our cross-lagged panel

model provided good fit [CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.000

(0.000; 0.078)] and accounted for 34.7% and 47.8% of the variance

in PDER and Impulsivity at T2, respectively. Analyses revealed

considerable stability in Impulsivity (b = 0.670; SE = 0.051; p < 0.001;

β = 0.659) between T1 and T2. In terms of the cross-lagged

associations, neither T1 PDER was associated with T2 Impulsivity

(b = −0.064; SE = 0.094; p = 0.496; β = −0.033), nor T1 Impulsivity

with T2 PDER (b = 0.019; SE = 0.096; p =0.845; β = 0.014). Child

age was significantly negatively associated with Impulsivity at T2

(b = −0.126; SE = 0.057; p = 0.028; β = −0.112; Table 3).

FIGURE 2

Summary of the cross-lagged panel analyses.

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 05 frontiersin.org

3.4 Cross-lagged panel model: effortful

control

Our model is presented in Figure 5. Our cross-lagged panel

model provided good fit [CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.000

(0.000; 0.000)] and accounted for 34.7% and 55.5% of the variance

in PDER and Effortful control at T2, respectively. Analyses

revealed considerable stability in Effortful control between T1 and

T2 (b = 0.716; SE = 0.050; p <0.001; β = 0.718). In terms of the

cross-lagged associations, T1 PDER significantly contributed to

lower Effortful control at T2 (b = −0.182; SE = 0.075; p =0.016;

β = −0.108), whereas T1 Effortful control did not contribute to

higher PDER at T2 (b = −0.002; SE = 0.129; p = 0.986; β = −0.001).

Parent age was also significantly negatively associated with Effortful

control at T2 (b = −0.019; SE = 0.008; p = 0.022; β = −0.098; Table 4).

4 Discussion

We investigated the relationships between parental digital

emotion regulation and self-regulation in children. Our study

revealed complex, bidirectional longitudinal associations between

TABLE 2 Results of the cross-lagged panel model measuring the bi-

directional associations between PDER (parental digital emotion

regulation) and the anger/frustration dimension of the child behavior

questionnaire.

Estimate (b) se p-value Beta

Child age → T2 PDER −0.168 0.118 0.155 −0.112

Child sex → T2 PDER −0.064 0.190 0.737 −0.025

T1 screen time → T2 PDER 0.054 0.043 0.209 0.105

Parent age → T2 PDER −0.022 0.025 0.359 −0.077

Parent sex → T2 PDER 0.018 0.382 0.962 0.004

Parent education → T2 PDER 0.127 0.146 0.384 0.073

Yearly income → T2 PDER −0.048 0.124 0.700 −0.028

T1 parenting stress → T2 PDER −0.002 0.013 0.870 −0.013

T1 PDER → T2 PDER 1.233 0.187 0.000 0.476

T1 Anger → T2 PDER 0.180 0.108 0.094 0.159

Child age → T2 Anger −0.021 0.072 0.768 −0.015

Child sex → T2 Anger −0.066 0.113 0.558 −0.029

T1 screen time → T2 Anger 0.063 0.024 0.009 0.133

Parent age → T2 Anger 0.020 0.014 0.153 0.073

Parent sex → T2 Anger −0.314 0.178 0.078 −0.072

Parent education → T2 Anger 0.066 0.082 0.425 0.041

Yearly income → T2 Anger 0.036 0.081 0.658 0.023

T1 parenting stress → T2 Anger 0.018 0.007 0.008 0.124

T1 anger → T2 Anger 0.567 0.054 0.000 0.546

T1 PDER → T2 Anger 0.304 0.122 0.013 0.128

FIGURE 3

Longitudinal cross-lagged associations between parental digital emotion regulation and the anger/frustration dimension of the child behavior

questionnaire.

FIGURE 4

Longitudinal cross-lagged associations between parental digital emotion regulation and the impulsivity dimension of the child behavior questionnaire.

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 06 frontiersin.org

the investigated variables. The results suggest that parental digital

emotion regulation may contribute to the bidirectional

association between media use and self-regulation in children

(37, 55, 62, 63). The observed associations were consistent and

strong in one direction (higher frequency of parental digital

emotion regulation leading to higher anger/frustration and lower

effortful control), but less consistent and more tendentious in the

other direction (effortful control does not, while anger/frustration

tendentiously contribute to higher PDER).

4.1 Higher PDER leads to poorer

anger/frustration management and

effortful control

Higher baseline occurrence of parental digital emotion

regulation (PDER) and higher baseline screen time predicted

poorer anger/frustration management (i.e., higher anger) one

year later. This is in line with findings of a cross-sectional study

(hence limitations regarding causal inferences) that more time

spent watching TV is associated with higher levels of negative

emotionality, emotional reactivity, and aggression, as well as

lower levels of soothability in toddlers (58). Longitudinal studies

(57, 62) found that baseline digital media use predicted more

externalizing problems (specifically, conduct problems and

hyperactivity) at follow-up, and these problems often entail

difficulties with anger management (75–78). While these

associations or effects can be driven by several mechanisms [e.g.,

direct effects, like overstimulation, and indirect effects, like

displacement of social interactions (79)], the present study

suggests that using digital devices for emotion regulation might

be a key determinant in the development of child difficulties

with various aspects of self-regulation. Our results somewhat

contradict those of Gordon-Hacker & Gueron-Sela (69), who

found in a path analysis that early maternal digital emotion

regulation preceded later negative emotionality only in children

FIGURE 5

Longitudinal cross-lagged associations between parental digital emotion regulation and the effortful control main factor of the child behavior

questionnaire.

TABLE 3 Results of the cross-lagged panel model measuring the bi-directional associations between PDER (parental digital emotion regulation) and the

impulsivity dimension of the child behavior questionnaire.

Estimate (b) se p-value Beta

Child age → T2 PDER −0.167 0.118 0.158 −0.114

Child sex → T2 PDER −0.059 0.189 0.755 −0.024

T1 Screen time → T2 PDER 0.064 0.043 0.138 0.127

Parent age → T2 PDER −0.025 0.025 0.304 −0.087

Parent sex → T2 PDER −0.007 0.395 0.986 −0.001

Parent education → T2 PDER 0.117 0.145 0.422 0.068

Yearly income → T2 PDER −0.037 0.121 0.761 −0.022

T1 parenting stress → T2 PDER 0.006 0.012 0.597 0.039

T1 PDER → T2 PDER 1.276 0.185 0.000 0.501

T1 Impulsivity → T2 PDER 0.019 0.096 0.845 0.014

Child age → T2 Impulsivity −0.126 0.057 0.028 −0.112

Child sex → T2 Impulsivity −0.122 0.087 0.160 −0.065

T1 screen time → T2 Impulsivity 0.022 0.021 0.297 0.057

Parent age → T2 Impulsivity −0.004 0.012 0.761 −0.016

Parent sex → T2 Impulsivity 0.203 0.145 0.164 0.057

Parent education → T2 Impulsivity 0.103 0.064 0.106 0.079

Yearly income → T2 Impulsivity −0.083 0.066 0.207 −0.065

T1 parenting stress → T2 Impulsivity −0.004 0.005 0.491 −0.031

T1 Impulsivity → T2 Impulsivity 0.670 0.051 0.000 0.659

T1 PDER → T2 Impulsivity −

0.064 0.094 0.496 −0.033

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 07 frontiersin.org

with low initial negative emotionality. However, it should be noted

that the authors found a significant, although weak (r = 0.2)

longitudinal correlation between T1 maternal digital emotion

regulation and T2 negative emotionality, and a slightly stronger

cross-sectional correlation (r = 0.37) between T2 maternal digital

emotion regulation and T2 negative emotionality, but neither of

them were significant in the path analysis. One possible

explanation for the divergent findings in their study and ours, is

the different age groups of the children. Additional explanation

for these somewhat contradictory results should be revealed

through further longitudinal studies. Furthermore, screen time

and PDER are closely related, and as the present design does

not allow for the separation of the two phenomena, further

research is needed to disentangle their respective effects on

child self-regulation.

Higher occurrence of PDER at T1 also predicted lower levels of

effortful control at T2. In line with this, longitudinal studies have

found that those who spend more time using digital devices

subsequently develop more attentional problems, impulsivity, and

poorer executive functions or self-regulation in general (37, 55,

61, 64, 80). These results corroborate the involvement of PDER

in developing self-regulation problems. Contrary to our

expectations, however, PDER in T1 did not predict impulsivity in

T2. This contrasts with the findings of several studies which

showed that digital device use leads to hyperactivity, inattention

or externalizing behaviors (81). It was also unexpected that T1

PDER predicted only effortful control, whereas impulsivity and

effortful control are related constructs (16, 17). The scale of

effortful control is made up of items on attentional focusing (e.g.,

Tendency to maintain attentional focus upon task-related

channels) and inhibitory control (e.g., The capacity to plan and

to suppress inappropriate approach responses under instructions

or in novel or uncertain situations). On the other hand,

impulsivity is defined as the “speed of response initiation” (71),

consisting of items like “Usually rushes into an activity without

thinking about it”. While high impulsivity entails low inhibitory

control, and both are related to behavioral self-regulation,

attentional focusing is a different, more cognitive construct and

does not necessarily correlate with the other two (82, 83). It is

possible that PDER affects attentional processes inherent to

effortful control to a larger extent than behavioral self-regulation.

Higher PDER is associated with higher screen time (38) and the

latter may have negative effects on attentional focusing (37, 80),

for example, as a result of overstimulation (84). The associations

between early digital media use and later attentional problems

are well supported by empirical data (37, 80), while relationships

between digital media use and executive functions are more

contradictory (54, 56, 61, 85–87). Therefore, further studies

should investigate the longitudinal associations of PDER with

attentional focusing and inhibitory control separately.

4.2 Poorer anger/frustration management

skills in T1, but not impulsivity and effortful

control, predicts tendentiously higher

occurrence of parental digital emotion

regulation in T2

Poorer baseline anger/frustration management skills (i.e.,

higher anger) tendentiously predicted higher occurrence of PDER

at follow-up. This result is in line with cross-sectional findings

showing that children with social-emotional difficulties, poor

self-regulation and a more difficult temperament have a higher

chance of being given digital technology as a calming tool or as a

baby-sitter (39, 43, 67, 68) and with longitudinal studies showing

that these problems lead to using more media later (37, 42,

TABLE 4 Results of the cross-lagged panel model measuring the bi-directional associations between PDER (parental digital emotion regulation) and the

effortful control main factor of the child behavior questionnaire.

Estimate (b) se p-value Beta

Child age → T2 PDER −0.168 0.120 0.160 −0.115

Child sex → T2 PDER −0.061 0.189 0.749 −0.024

T1 Screen time → T2 PDER 0.066 0.042 0.118 0.130

Parent age → T2 PDER −0.025 0.025 0.303 −0.088

Parent sex → T2 PDER −0.008 0.395 0.983 −0.002

Parent education → T2 PDER 0.117 0.146 0.423 0.068

Yearly income → T2 PDER −0.039 0.120 0.749 −0.023

T1 parenting stress → T2 PDER 0.006 0.012 0.618 0.038

T1 PDER → T2 PDER 1.275 0.186 0.000 0.500

T1 effortful control → T2 PDER −0.002 0.129 0.986 −0.001

Child age → T2 Effortful control −0.066 0.048 0.164 −0.068

Child sex → T2 Effortful control 0.091 0.071 0.202 0.055

T1 screen time → T2 Effortful control −0.015 0.016 0.349 −0.044

Parent age → T2 Effortful control −0.019 0.008 0.022 −0.098

Parent sex → T2 Effortful control −0.108 0.139 0.437 −0.035

Parent education → T2 Effortful control 0.013 0.049 0.788 0.012

Yearly income → T2 Effortful control 0.039 0.048 0.418 0.035

T1 parenting stress → T2 Effortful control 0.005 0.006 0.383 0.046

T1 effortful control → T2 Effortful control 0.716 0.050 0.000 0.718

T1 PDER → T2 Effortful control −

0.182 0.075 0.016 −0.108

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 08 frontiersin.org

62, 64). Our study is the first longitudinal study in support of poor

emotion regulation leading to higher chances of parental digital

emotion regulation, although the association was only marginally

significant (p = 0.094). Parents with difficult children may

struggle more with decreasing the tempers or negative emotions

of the child. Therefore, they may turn to digital devices to

alleviate their burden. As Radesky et al. (39) pointed out,

“frustration with the child’s behavior would lead to use of digital

media as a coping strategy” (p. 397). Similarly, instrumental use

of media (using media as a behavior modifier or as a babysitter)

was primarily endorsed by parents who are less confident about

their parenting (68), and children with difficult temperament

may contribute to parents being less confident about their

parenting skills (88, 89).

Impulsivity and effortful control did not predict later PDER.

This suggests that parents use digital media as a parenting tool

only for managing emotional self-regulation problems in the

child, but not cognitive or behavioral self-regulation problems.

This result is unexpected, but may reflect the fact that

impulsivity and lower effortful control in the child may be less

challenging for the parent than anger management problems, as

the latter entails emotional outburst and tantrums. Some studies

(67, 68) indicate that impulsivity and lower effortful control

(specifically, conduct problems and energetic temperaments) are

associated with PDER. However these studies are cross-sectional

and cannot inform causal nor directional inferences. The present

longitudinal study suggests that these self-regulatory tendencies

do not lead to PDER, but rather the other way around as we

found that PDER led to lower effortful control. Although many

longitudinal studies found that children with attentional

problems, higher impulsivity and lower self-regulation at baseline

consume more digital media later (37, 62, 64, 79), these effects

may not be driven by parental motivation to regulate the child’s

behavior/emotion by digital devices. Based on our results, we

argue it is likely that children with these problems are more

prone to use digital devices, independently of how much their

parents try to regulate their behavior with the device.

4.3 Limitations

To draw appropriate conclusions from the results, some

limitations should be addressed.

PDER was solely measured by parent report and with only one

item. More elaborate measures are required in future studies to

corroborate the present findings, and parent reported PDER

should be validated by behavioral observations. Parents also

reported child self-regulation tendencies, which could lead to

shared measurement bias. Replications with reports from

preschool teachers or using different methodologies engaging

parents more actively to support their recall memories or

opinions about their child’s behavior could advance future studies.

The internal consistency for impulsivity was lower than

desirable (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.629 in Wave 1 and 0.656 in

Wave 2). This might have reduced the statistical power of the

analysis to detect associations with PDER. Additionally, the

dimensions of impulsivity and anger have rarely been used

separately (90). Although their reliability has been frequently

proven to be satisfactory (71, 73), the validity of these subscales

is less known with few existing studies showing moderate

correlations with other questionnaire scales (91), and low to

moderate correlations with laboratory observational measures

(92, 93). In the future, more studies are required to better

corroborate the construct validity of these subscales.

Another potential confounder of the results is that data

collection took place during a provincially declared state of

emergency and lockdown because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Since digital device use increased during lockdowns (94, 95), our

findings should be replicated in post pandemic contexts.

Additionally, convenience sampling may not be representative

of the general population. This decreases the generalizability of the

results to the whole population. Replications with larger sample are

warranted. On the other hand, random sampling makes it

impossible to separate the effects of screen time and PDER (as

they are closely related). Therefore, further research is needed to

disentangle their effects on self-regulation.

Lastly, the unretained sample differed from the retained sample

in that parents in the unretained sample were younger and

marginally used more PDER than the retained participants. This

might have caused a systematic bias in the sample. Those who

participated in the second data collection wave might be more

conscious parents (applying less PDER), and this may distort the

observed associations. For example, it is possible that the

association between T1 effortful control and impulsivity and T2

PDER was not significant (and between T1 anger and T2 PDER

was only marginally signifi cant) because conscious parents try to

find other ways besides digital media to regulate or engage the

child. These shortcomings should be addressed in future studies.

4.4 Conclusion

Our study is the first longitudinal study revealing bidirectional

associations between parental digital emotion regulation and child

emotion-regulation skills. Results support that higher anger/

frustration in the child renders parents tendentiously more likely

use digital devices to regulate child emotions. However, while

digital emotion regulation can be effective in the short term, this

strategy may hinder child development of self-regulatory skills in

the long term, leading to poorer effortful control and anger

management. This process may lead to a positive feedback loop,

resulting in increased dependence on the digital device and

potential later problematic media use, “screen time tantrums”

(40), and technological addiction (96). Based on these results,

efforts should be made to call parents’ attention on the harmful

consequences of digital emotion regulation. Pediatricians, child

psychologists, health professionals, and social workers working

directly with families or performing home visits should ask

parents about the use of digital media in the family. Additionally,

they should be especially attentive to parents of children with

difficult temperament, as they may be at higher risk of using

PDER. These parents should receive as much support as possible

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 09 frontiersin.org

to reinforce emotion regulation methods other then PDER. In

addition, peoples’ awareness should be increased about digital

devices being inappropriate tools for curing tantrums.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be

made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Université de

Sherbrooke’s IRB #2021-2927. The studies were conducted in

accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

The participants provided their written informed consent to

participate in this study.

Author contributions

VK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft,

Visualization, Funding acquisition, Formal Analysis,

Conceptualization. M-AB: Project administration, Writing –

review & editing, Writing – original draft. ÁK: Writing – review

& editing, Writing – original draft. ÁP: Writing – review &

editing, Funding acquisition. ÁM: Writing – review & editing,

Funding acquisition. CF: Writing – review & editing,

Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the

research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health

Research (CIHR), Social sciences and humanities research

council (SSHRC), Nova Scotia Research (NSR), and the Canada

Research Chairs program (CRC), the National Research,

Development and Innovation Office (OTKA K 135478; OTKA

PD 134984), the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA post-

covid 2021-50; Bolyai János Research Fellowship; MTA 01 031)

and the European Union project RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00004

(Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory). AP was funded by

the Hungarian Ethology Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the

absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could

be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the

authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated

organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the

reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or

claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed

or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Konok V, Bunford N, Miklósi Á. Associations between child mobile use and

digital parenting style in Hungarian families. J Child Media. (202 0) 14(1):91–109.

doi: 10.1080/17482798.2019.1684332

2. Gallup. Time to play: a study on children’s free time: how it is spent, proritized

and valued (2017). Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/reports/214853/time-

play-study-children-free-time-spent-prioritized-valued.aspx (Accessed February 02,

2023).

3. Carson V, Ezeugwu VE, Tamana SK, Chikuma J, Lefebvre DL, Azad MB, et al.

Associations between meeting the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the

early years and behavioral and emotional problems among 3-year-olds. J Sci Med

Sport. (2019) 22(7):797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.01.003

4. Madigan S, Racine N, Tough S. Prevalence of preschoolers meeting vs exceeding

screen time guidelines. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174(1):93–5. doi: 10.1001/

jamapediatrics.2019.4495

5. Madigan S, Eirich R, Pador P, McArthur BA, Neville RD. Assessment of changes

in child and adolescent screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic : a systematic

review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176(12):1188–98. doi: 10.1001/

jamapediatrics.2022.4116

6. Rideout V, Robb MB. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to

Eight, 2020. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media (2020).

7. Newall M, Machi S. Parents try to limit children’s screen time as it increases

during pandemic. Ipsos (2020). Available online at: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/

parents-try-limit-childrens-screen-time-it-increases-during-pandemic (Accessed

February 10, 2023).

8. Lissak G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on

children and adolescents: literature review and case study. Environ Res. (2018)

164:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.015

9. Green CS, Bavelier D. Exercising your brain: a review of human brain plasticity

and training-induced learning. Psychol Aging. (2008) 23(4):692–701. doi: 10.1037/

a0014345

10. Tromholt M. The facebook experiment: quitting facebook leads to higher levels

of well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2016) 19(11):661–6. doi: 10.1089/cyber.

2016.0259

11. Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Hashizume H, Asano K, Asano M, Sassa Y, et al. The

impact of television viewing on brain structures: cross-sectional and longitudinal

analyses. Cereb Cortex. (2015) 25(5):1188–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht315

12. Horowitz-Kraus T, Hutton JS. Brain connectivity in children is increased by the

time they spend reading books and decreased by the length of exposure to screen-

based media. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. (2018) 107(4):685–93. doi: 10.1111/apa.

14176

13. Hutton JS, Dudley J, DeWitt T, Horowitz-Kraus T. Associations between digital

media use and brain surface structural measures in preschool-aged children. Sci Rep.

(2022) 12(1):19095.

14. Shin M, Kemps E. Media multitasking as an avoidance coping strategy against

emotionally negative stimuli. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2020) 33(4):440–51. doi: 10.

1080/10615806.2020.1745194

15. Jahromi LB. Self-regulation in young children with autism spectrum disorder:

an interdisciplinary perspective on emotion regulation, executive function,

and effortful control. Int Rev Res Dev Disabil. (2017) 53:45–89. doi: 10.1016/bs.

irrdd.2017.07.007

16. Holzman JB, Bridgett DJ. Heart rate variability indices as bio-markers of top-

down self-regulatory mechanisms: a meta-analytic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.

(2017) 74:233–

55. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.032

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 10 frontiersin.org

17. Nigg JT. Annual research review: on the relations among self-regulation, self-

control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-

taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. (2017) 58(4):361–83. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12675

18. Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood:

continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Dev

Psychol. (2000) 36(2):220. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.220

19. Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM,

editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality

Development. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc (2006). p. 99–166. https://

psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-08776-000 (Accessed February 17, 2023).

20. Eisenberg N, Smith CL, Spinrad TL. Effortful control: relations with emotion

regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF,

editors. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. 3rd ed.

New York: Guilford Press (2017). p. 458–78.

21. Lengua LJ, Honorado E, Bush NR. Contextual risk and parenting as predictors of

effortful control and social competence in preschool children. J Appl Dev Psychol.

(2007) 28(1):40–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.10.001

22. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq.

(2015) 26(1):1–26. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

23. Stifter CA, Spinrad TL. The effect of excessive crying on the development of

emotion regulation. Infancy. (2002) 3(2):133–52. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_2

24. Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct:

methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Dev.

(2004) 75(2):317–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x

25. Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: a theme in search of definition. Monogr Soc

Res Child Dev. (1994) 59(2–3):25–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834 .1994.tb01276.x

26. Stifter CA. Individual differences in emotion regulation in infancy: a thematic

collection. Infancy. (2002) 3(2):129–32. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_1

27. Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family

context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev. (2007) 16(2):361–88.

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

28. Wadley G, Smith W, Koval P, Gross JJ. Digital emotion regulation. Curr Dir

Psychol Sci. (2020) 29(4):412–8. doi: 10.1177/0963721420920592

29. Villani D, Carissoli C, Triberti S, Marchetti A, Gilli G, Riva G. Videogames for

emotion regulation: a systematic review. Games Health J. (2018) 7(2):85–99. doi: 10.

1089/g4h.2017.0108

30. Sonnentag S, Fritz C. The recovery experience questionnaire: development and

validation of a measure for assessi ng recuperation and unwinding from work. J Occup

Health Psychol. (2007) 12(3):204–21. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204

31. Reinecke L. Games and recovery. J Media Psychol. (2009a) 21(3):126

–42. doi: 10.

1027/1864-1105.21.3.126

32. Reinecke L. Games at work: the recreational use of computer games during

working hours. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2009b) 12(4):461–5. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2009.0010

33. Weber R, Tamborini R, Westcott-Baker A, Kantor B. Theorizing flow and media

enjoyment as cognitive synchronization of attentional and reward networks. Commun

Theory. (2009) 19(4):397–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2009.01352.x

34. Yee N. Motivations for play in online games. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2006) 9

(6):772–5. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772

35. Koepp MJ, Gunn RN, Lawrence AD, Cunningham VJ, Dagher A, Jones T, et al.

Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game. Nature. (1998) 393

(6682):266–8. doi: 10.1038/30498

36. Han DH, Lee YS, Yang KC, Kim EY, Lyoo IK, Renshaw PF. Dopamine genes and

reward dependence in adolescents with excessive internet video game play. J Addict

Med. (2007) 1(3):133–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31811f465f

37. Gentile DA, Swing EL, Lim CG, Khoo A. Video game playing, attention

problems, and impulsiveness: evidence of bidirectional causality. Psychol Pop Media

Cult. (2012) 1(1):62–70. doi: 10.1037/a0026969

38. Beyens I, Eggermont S. Putting young children in front of the television:

antecedents and outcomes of parents’ use of television as a babysitter. Commun Q.

(2014) 62(1):57–74. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2013.860904

39. Radesky JS, Peacock-Chambers E, Zuckerman B, Silverstein M. Use of mobile

technology to calm upset children. JAMA Pediatr. (2016) 170(4):397. doi: 10.1001/

jamapediatrics.2015.4260

40. Coyne SM, Shawcroft J, Gale M, Gentile DA, Etherington JT, Holmgren H, et al.

Tantrums, toddlers and technology: temperament, media emotion regulation, and

problematic media use in early childhood. Comput Human Behav. (2021) 120

(February):106762. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106762

41. Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, Budacki JG, Mohanty SH, Leister KP,

et al. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics. (2015)

136(6):1044–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2151

42. Radesky JS, Silverstein M, Zuckerman B, Christakis DA. Infant self-regulation

and early childhood media exposure. Pediatrics. (2014) 133(5):e1172–8. doi: 10.

1542/peds.2013-2367

43. Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Maternal characteristics and perception of

temperament associated with infant TV exposure. Pediatrics. (2013) 131(2):e390–7.

doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1224

44. Ar undell L, Gould L, Ridgers ND, Ayala AMC, Downing KL, Salmon J, et al.

“Everything kind of revolves around technology”: a qualitative exploration of

families’ screen use experiences, and intervention suggestions. BMC Public Health.

(2022) 22(1):1606. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14007-w

45. Roberts MZ, Flagg AM, Lin B. Context matters: how smartphone (mis)use may

disrupt early emotion regulation development. New Ideas Psychol. (2022) 64(March

2021):100919. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100919

46. Davis EL, Quiñones-Camacho LE, Buss KA. The effects of distraction and

reappraisal on children’s parasympathetic regulation of sadness and fear. J Exp

Child Psychol. (2016) 142:344–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.020

47. Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: physiology, self-report, and

expressive behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol . (1993) 64(6):970–86. doi: 10.1037/0022-

3514.64.6.970

48. Hiniker A, Suh H, Cao S, Kientz JA. Screen time tantrums. Proceedings of the

2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2016). p. 648–60.

doi: 10.1145/2858036.2858278

49. Hadar AA, Eliraz D, Lazarovits A, Alyagon U, Zangen A. Using longitudinal

exposure to causally link smartphone usage to changes in behavior, cognition and

right prefrontal neural activity. Brain Stimul. (2015) 8(2):318. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.

2015.01.032

50. Wilmer HH, Chein JM. Mobile technology habits: patterns of association among

device usage, intertemporal preference, impulse control, and reward sensitivity.

Psychon Bull Rev. (2016) 23(5):1607–14. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1011-z

51. Minear M, Brasher F, McCurdy M, Lewis J, Younggren A. Working memory,

fluid intelligence, and impulsiveness in heavy media multitaskers. Psychon Bull Rev.

(2013) 20(6):1274–81. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0456-6

52. Sanbonmatsu DM, Strayer DL, Medeiros-Ward N, Watson JM. Who multi-tasks

and why? Multi-tasking ability, perceived multi-tasking ability, impulsivity,

and sensation seeking. PLoS One. (2013) 8(1):e54402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.

0054402

53. Shih S-I. A null relationship between media multitasking and well-being. PLoS

One. (2013) 8(5):e64508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064508

54. Nathanson AI, Aladé F, Sharp ML, Rasmussen EE, Christy K. The relation

between television exposure and executive function among preschoolers. Dev

Psychol. (2014) 50(5):1497–506. doi: 10.1037/a0035714

55. McHarg G, Ribner AD, Devine RT, Hughes C. Screen time and executive

function in toddlerhood: a longitu dinal study. Front Psychol. (2020b) 11:570392.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570392

56. Corkin MT, Peterson ER, Henderson AME, Waldie KE, Reese E, Morton SMB.

Preschool screen media exposure, executive functions and symptoms of

inattention/hyperactivity. J Appl Dev Psychol. (2021) 73:101237. doi: 10.1016/j.

appdev.2020.101237

57. McNeill J, Howard SJ, Vella SA, Cliff DP. Longitudinal associations of electronic

application use and media program viewing with cognitive and psychosocial

development in preschoolers. Acad Pediatr. (2019) 19(5):520 –8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.

2019.02.010

58. Desmarais E, Brown K, Campbell K, French BF, Putnam SP, Casalin S, et al.

Links between television exposure and toddler dysregulation: does culture matter?

Infant Behav Dev. (2021) 63(March):101557. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2 021.101557

59. Lawrence AC, Narayan MS, Choe DE. Association of young children’s use of

mobile devices with their self-regulation. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174(8):793–5.

American Medical Association. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0129

60. Cerniglia L, Cimino S, Ammaniti M. What are the effects of screen time on

emotion regulation and academic achievements? A three-wave longitudinal study on

children from 4 to 8 years of age. J Early Child Res. (2021) 19(2):145–60. doi: 10.

1177/1476718X20969846

61. McHarg G, Ribner AD, Devine RT, Hughes C. Infant screen exposure links to

toddlers’

inhibition, but not other EF constructs: a propensity score study. Infancy.

(2020a) 25(2):205–22. doi: 10.1111/infa.12325

62. Poulain T, Vogel M, Neef M, Abicht F, Hilbert A, Genuneit J, et al.

Reciprocal associations between electronic media use and behavioral difficulties in

preschoolers. Int J Environ Res Public Health . (2018) 15(4):814. doi: 10.3390/

ijerph15040814

63. Paulus FW, Hübler K, Mink F, Möhler E. Emotional dysregulation in preschool

age predicts later media use and gaming disorder symptoms in childhood. Front

Psychiatry. (2021) 12(June):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626387

64. Cliff DP, Howard SJ, Radesky JS, McNeill J, Vella SA. Early childhood media

exposure and self-regulation: bidirectional longitudinal associations. Acad Pediatr.

(2018) 18(7):813–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.04.012

65. Spinrad TL, Stifter CA. Toddlers’ empathy-related responding to distress:

predictions from negative emotionality and maternal behavior in infancy. Infancy.

(2006) 10(2):97–121. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in1002_1

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 11 frontiersin.org

66. Hagan MJ, Luecken LJ, Modecki KL, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA. Childhood

negative emotionality predicts biobehavioral dysregulation 15 years later. Emotion.

(2016) 16(6):877–85. doi: 10.1037/emo0000161

67. Nabi RL, Krcmar M. It takes two: the effect of child characteristics on U.S.

parents’ motivations for allowing electronic media use. J Child Media. (2016) 10

(3):285–303. doi: 10.1080/17482798.201 6.1162185

68. Nikken P. Parents’ instrumental use of media in childrearing: relationships with

confidence in parenting, and health and conduct problems in children. J Child Fam

Stud. (2019) 28(2):531–46. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1281-3

69. Gordon-Hacker A, Gueron-Sela N. Maternal use of media to regulate child

distress: a double-edged sword? Longitudinal links to toddlers’ negative

emotionality. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23(6):400–5. doi: 10.1089/cyber.

2019.0487

70. Barr R, Kirkorian H, Radesky J, Coyne S, Nichols D, Blanchfield O, et al. Beyond

screen time: a synergistic approach to a more comprehensive assessment of family

media exposure during early childhood. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1283. doi: 10.3389/

fpsyg.2020.01283

71. Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Development of short and very short forms of the

children’s behavior questionnaire. J Pers Assess. (2006) 87(1):102–12. doi: 10.1207/

s15327752jpa8701_09

72. Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. 4th ed. FL: PAR (2012).

73. Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at

three to seven years: the children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Dev. (2001) 72

(5):1394–408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355

74. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 8.10). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén &

Muthén (2023).

75. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (Vol. 5, Issue 5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

(2022). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

76. Ramirez CA, Rosén LA, Deffenbacher JL, Hurst H, Nicoletta C, Rosencranz T,

et al. Anger and anger expression in adults with high ADHD symptoms. J Atten

Disord. (1997) 2(2):115–28. doi: 10.1177/108705479700200205

77. Braaten EB, Rosén LA. Self-regulation of affect in attention deficit-hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD) and non-ADHD boys: differences in empathic responding.

J Consult Clin Psychol. (2000) 68(2):313–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.313

78. Richards TL, Deffenbacher JL, Rosén LA. Driving anger and other driving-

related behaviors in high and low ADHD symptom coll ege students. J Atten Disord.

(2002) 6(1):25–38. doi: 10.1177/108705470200600104

79. Konok V, Szőke R. Longitudinal associations of children’

s hyperactivity/

inattention, peer relationship problems and mobile device use. Sustainability. (2022)

14(14):1–18. doi: 10.3390/su14148845

80. Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Associations between content types of early

media exposure and subsequ ent attentional problems. Pediatrics. (2007) 120

(5):986–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3322

81. Nikkelen SWC, Valkenburg PM, Huizinga M, Bushman BJ. Media use and

ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Dev Psychol.

(2014) 50(9):2228–41. doi: 10.1037/a0037318

82. Kuntsi J, Pinto R, Price TS, van der Meere JJ, Frazier-Wood AC, Asherson P.

The separation of ADHD inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms:

pathways from genetic effects to cognitive impairments and symptoms. J Abnorm

Child Psychol. (2014) 42(1):127–36. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9771-7

83. Toplak ME, Pitch A, Flora DB, Iwenofu L, Ghelani K, Jain U, et al. The unity and

diversity of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in ADHD: evidence for a general

factor with separable dimensions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2009) 37(8):1137–50.

doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9336-y

84. Christakis DA, Benedikt Ramirez JS, Ferguson SM, Ravinder S, Ramirez JM.

How early media exposure may affect cognitive function: a review of results from

observations in humans and experiments in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2018)

115(40):9851–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.17 11548115

85. Flynn RM, Richert RA. Cognitive, not physical, engagement in video gaming

influences executive functioning. J Cogn Dev. (2018) 19(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/

15248372.2017.1419246

86. Huber B, Yeates M, Meyer D, Fleckhammer L, Kaufman J. The effects of screen

media content on young children’s executive functioning. J Exp Child Psychol. (2018)

170:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.01.006

87. Jusienė R, Rakickienė L, Breidokienė R, Laurinaitytė I. Executive function and

screen-based media use in preschool children. Infant Child Dev. (2020) 29(1):e2173.

doi: 10.1002/icd.2173

88. Gross D, Conrad B, Fogg L, Wothke W. A longitudinal model of maternal self-

efficacy, depression, and difficult temperament during toddlerhood. Res Nurs Health.

(1994) 17(3):207–15. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170308

89. Takács L, Smo lík F, Putnam S. Assessing longitudinal pathways between

maternal depressive symptoms, parenting self-esteem and infant temperament. PLoS

One. (2019) 14(8):e0220633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220633

90. Fitzpatrick C, Binet MA, Harvey E, Barr R, Couture M, Garon-Carrier G.

Preschooler screen time and temperamental anger/frustration during the COVID-19

pandemic. Pediatr Res. (2023) 94(2):820–5. doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02485-6

91. Lim JY, Bae YJ. Validation study of Korean version of the Rothbart’s children’s

behavior questionnaire.

Korean J Hum Ecol. (2015) 24(4):477–97. doi: 10.5934/kjhe.

2015.24.4.477

92. Majdandžić M, Van Den Boom DC. Multimethod longitudinal assessment of

temperament in early childhood. J Pers. (2007) 75(1):121–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-

6494.2006.00435.x

93. Majdandžić M, van den Boom DC, Heesbeen DG. Peas in a pod: biases in the

measurement of sibling temperament? Dev Psychol. (2008) 44(5 ):1354. doi: 10.1037/

a0013064

94. Ribner AD, Coulanges L, Friedman S, Libertus ME, Hughes C, Foley S, et al.

Screen time in the coronavirus 2019 era: international trends of increasing use

among 3- to 7-year-old children. J Pediatr. (2021) 239:59–66.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.

jpeds.2021.08.068

95. Eales L, Gillespie S, Alstat RA, Ferguson GM, Carlson SM. Children’s screen and

problematic media use in the United States before and during the COVID-19

pandemic. Child Dev. (2021) 92(5):e866–82. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13652

96. Sherer J, Levounis P. Technological addictions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2022) 24

(9):399–406. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01351-2

Konok et al. 10.3389/frcha.2024.1276154

Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 12 frontiersin.org