+63&>3<!=C@</:=4&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G+63&>3<!=C@</:=4&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G

-=:C;3

AAC3

.7<B3@

@B71:3

!/<C/@G

)3:/B7=<A67>A3BE33<*3<A=@G'@=13AA7<5+3;>3@/;3<B)3:/B7=<A67>A3BE33<*3<A=@G'@=13AA7<5+3;>3@/;3<B

6/@/1B3@7AB71A4=@44=@B4C:=<B@=:/<2F31CB7D3C<1B7=<7<6/@/1B3@7AB71A4=@44=@B4C:=<B@=:/<2F31CB7D3C<1B7=<7<

*16==:5367:2@3<*16==:5367:2@3<

)/163:7/;/<B

+*B7::,<7D3@A7BG=43/:B6*173<13A,*

@27/;/<B/BAC32C

%/B/A6/*;3B

%=@B63@<@7H=</,<7D3@A7BG,*

</B/A6/A;3B</C32C

=::=EB67A/<2/227B7=</:E=@9A/B6BB>AA16=:/@E=@9AE;71632C=8=B

'/@B=4B63&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G=;;=<A

)31=;;3<2327B/B7=<)31=;;3<2327B/B7=<

7/;/<B)*;3B%)3:/B7=<A67>A3BE33<*3<A=@G'@=13AA7<5+3;>3@/;3<B

6/@/1B3@7AB71A4=@44=@B4C:=<B@=:/<2F31CB7D3C<1B7=<7<*16==:5367:2@3<

+63&>3<!=C@</:=4

&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G

6BB>A2=7=@5

+67A2=1C;3<B6/A033</113>B324=@7<1:CA7=<7<+63&>3<!=C@</:=4&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G0GB63327B=@A@33

=>3</113AA7A>@=D72320G*16=:/@.=@9A/B.$,=@;=@37<4=@;/B7=<>:3/A31=<B/1BE;C

A16=:/@E=@9AE;71632C

)3:/B7=<A67>A3BE33<*3<A=@G'@=13AA7<5+3;>3@/;3<B6/@/1B3@7AB71A4=@)3:/B7=<A67>A3BE33<*3<A=@G'@=13AA7<5+3;>3@/;3<B6/@/1B3@7AB71A4=@

44=@B4C:=<B@=:/<2F31CB7D3C<1B7=<7<*16==:5367:2@3<44=@B4C:=<B@=:/<2F31CB7D3C<1B7=<7<*16==:5367:2@3<

0AB@/1B0AB@/1B

/195@=C<2

*3<A=@G>@=13AA7<5036/D7=@AB63B3;>3@/;3<B16/@/1B3@7AB714=@344=@B4C:1=<B@=:/<2

3F31CB7D34C<1B7=<>@=;=B3A3:4@35C:/B7=</1B7D7BG3<5/53;3<B/<2>@=0:3;A=:D7<5+67AABC2G

3F/;7<327<B3@@3:/B7=<A67>A03BE33<3F31CB7D34C<1B7=<344=@B4C:1=<B@=:/<2A3<A=@G>@=13AA7<57<

A16==:/532167:2@3<03BE33</<2G3/@A=4/53

$3B6=2

3A1@7>B7D31=@@3:/B7=<@3A3/@1623A75<E/ACA32B=3F/;7<3@3:/B7=<A67>A=4=CB1=;3A4@=;

B6@331/@357D3@@3>=@B32AB/<2/@27H32?C3AB7=<</7@3A=4036/D7=@A@3:/B32B=A3<A=@G>@=13AA7<5

*3<A=@G'@=J:3

344=@B4C:1=<B@=:

+3;>3@/;3<B7<$722:367:26==2(C3AB7=<</7@3

/<23F31CB7D3

4C<1B7=<

36/D7=@)/B7<5 <D3<B=@G=4F31CB7D3C<1B7=<

7<2/7:G/1B7D7B73A%

)3AC:BA

/B//</:GA7ACA7<523A1@7>B7D3AB/B7AB71A/<2*>3/@;/<IA

)

@3D3/:32AB/B7AB71/::GA75<7J1/<B

>

D/:C3>=A7B7D3/<2<35/B7D31=@@3:/B7=<A03BE33<1=<AB@C1BA=43F31CB7D34C<1B7=<344=@B4C:

1=<B@=:/<2A3<A=@G>@=13AA7<5036/D7=@A&<:G>=A7B7D31=@@3:/B7=<AE3@34=C<203BE33<A3<A=@G

>@=13AA7<5036/D7=@A/<23F31CB7D34C<1B7=<

=<1:CA7=<

7<27<5A7<271/B3B6/BBG>71/:@3A>=<A3AB=A3<A=@G3F>3@73<13AE3@3@3:/B32B=BG>71/:

/07:7B73A4=@3F31CB7D34C<1B7=</<2344=@B4C:1=<B@=:E63@3/A7<1@3/A32A3<A=@G@3/1B7D7BGE/A/AA=17/B32

E7B6231@3/A32/07:7B73A4=@3F31CB7D34C<1B7=</<2344=@B4C:1=<B@=:/:=<5E7B6/<7<1@3/A323F>@3AA7=<=4

7;>C:A7D7BG@32C132/BB3<B7=</<2231@3/A32=<B/A9036/D7=@&CB1=;3AAC>>=@BB63<332B=/22@3AA

A3<A=@G@3A>=<A7D3<3AA/<2@3/1B7D7BG7<B631=<B3FBB=AC>>=@B036/D7=@;/</53;3<B4=@344=@B4C:

1=<B@=:/<23F31CB7D34C<1B7=<

=;;3<BA

+63/CB6=@A231:/@3B6/BB63G6/D3<=1=;>3B7<5J</<17/:>@=43AA7=</:=@>3@A=</:7<B3@3ABB6/B;756B

6/D37<KC3<132B63>3@4=@;/<13=@>@3A3<B/B7=<=4B63E=@923A1@70327<B67A;/<CA1@7>B

"3GE=@2A"3GE=@2A

/BB3<B7=<4=1CA036/D7=@/:7<6707B7=<A3:4@35C:/B7=<A3<A=@G

=D3@'/53==B<=B3=D3@'/53==B<=B3

7</<17/:AC>>=@BE/A>@=D72320G/./@<3@3@;/BC@=/<2+*,=/@2=4+@CAB33A)3A3/@16@/<B

AA7AB/<13E7B6@31@C7B;3<B2/B/1=::31B7=</<2A1=@7<5=4?C3AB7=<</7@3AE/A>@=D72320G:3F/<2@/

=<B@3@/A&+&+)#@7<*C::7D/<&+&+)#=::7)C7H&+&+)#/<2"/B63@7<3=:;3A&+

&+)#

@323<B7/:A7A>:/G

@)/163:7/;/<B'6&+)#'

@%/B/A6/*;3B&+&+)#

=>G@756BB@/<A43@/5@33;3<BA/@3<=B=0B/7<320G+63&>3<!=C@</:=4&11C>/B7=</:+63@/>G

&!&+)3>@7<B>3@;7AA7=<4=@B67A>>:732)3A3/@16A6=C:203=0B/7<324@=;B63

1=@@3A>=<27<5/CB6=@A:71963@3B=D73E=C@=>3</113AAAB/B3;3<B@35/@27<5CA3@@756BA

/<227AB@70CB7=<=4B67A>>:732)3A3/@16

Sensory processing behaviors have been identified as a factor in self-regulation and emotional

development in children (Critz et al., 2015; Dunn, 2007; Miller et al., 2007). Temperament and executive

function have been identified as neurological factors in behavioral styles, self-regulation, and social-

emotional development in children (Dixon et al., 2006; Edossa et al., 2018; Gioia et al., 2015; Henderson

& Wachs, 2007; Janson & Mathiesen, 2008; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Research regarding the

relationships between temperament and sensory processing behaviors indicates that descriptive features

of temperament and descriptive features of sensory processing behaviors are interrelated (DeSantis et al.,

2011; Diamant, 2011; Gouze et al., 2012). Findings show that extreme behavioral reactivity toward

sensory experiences can play a role in the development of behavioral issues in children (DeSantis et al.,

2011; Gouze et al., 2012). Children with diagnostic conditions, such as autism, attention deficit disorder,

and reactive attachment disorder, often demonstrate issues with behavioral self-regulation and executive

functions (Critz et al., 2015; Diamond, 2013). Thus, the ability to identify factors that influence behavioral

self-regulation in children is a critical component in intervention planning and positive outcomes

regarding behavior management and activity engagement.

Behavioral Self-Regulation

Behavioral self-regulation is a construct that encompasses one’s ability to actively or passively

engage and respond to the demands of tasks and the physical and/or social environments (Dunn, 2007).

Individuals adjust their emotions, cognition, and behavior according to internal (i.e., body responses) and

external demands (i.e., contextual experiences) (McClelland et al., 2010). A child’s ability to adjust

emotions and behavior is a developmental process that emerges through daily experiences and

cultural/social expectations. Self-regulatory skills are crucial in early development and throughout the

lifespan and can have an influence on behavioral management and academic success (Caughy et al., 2018).

Several factors influence behavioral self-regulation, including brain and physiological maturation,

parenting styles, peer socialization, and contextual demands (Edossa et al., 2018; McClelland et al., 2010;

Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Temperament and Effortful Control

Temperament is a compilation of behavior characteristics in a continuum and describes how an

individual may approach or interact within his or her context (Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences,

2016; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Zentner & Bates, 2008). Temperament characteristics include behavioral

responses to fear, anger and frustration, positive affect and approach, activity level, inhibition, and

attention that relate to capacities that form individual differences in personality (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Theories of temperament indicate that differences in emotionality, activity level, and attention are based

on brain systems that shape a child’s behavioral reactivity and self-regulation (Institute for Learning &

Brain Sciences, 2016; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Zentner & Bates, 2008).

Effortful control is a temperament characteristic defined by the ability to modulate responses, plan,

focus, and regulate emotions and actions through behavioral inhibition (Diamond, 2013; Simonds &

Rothbart, 2004). For example, according to Rothbart and Bates (2006), children with strong abilities for

effortful control can put off a desired activity, wait for a desired activity, or complete a less desirable

activity before starting a more desirable activity. Other children with fewer abilities for effortful control

might be more impulsive, more distracted, less attentive and/or have issues with task completion (Rothbart

& Bates, 2006). Thus, attentional control and inhibitory control are key components of effortful control

(Zentner & Bates, 2008).

1

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

Executive Function

Executive function is the neurological ability to direct or manage cognitive, emotional, and

behavioral functions to problem-solve. It involves three core abilities: inhibitory control, working

memory, and cognitive flexibility (Diamond, 2013). Inhibitory control allows an individual to control

impulses and respond appropriately to the situation. Working memory is the ability to use stored

information for application in an appropriate situation at a later time (Diamond, 2013). Cognitive

flexibility allows for adaptive thinking, taking responsibility for actions, and accepting unexpected

challenges (Diamond, 2013).

Sensory Processing

Sensory processing is the ability to receive and detect sensory input through the nervous system

and modulate, integrate, organize, and interpret the information to create a response (Dunn, 2001; Dunn,

2007). These responses can occur differently between individuals and conditions and influence mood,

temperament, activity choices, and participation (Dunn, 2001; Dunn, 2007). The Model of Sensory

Processing describes sensory-based behavioral responses routinely experienced in everyday activities

(Dunn, 2001; Dunn, 2007). This model identifies four sensory processing behavior patterns that describe

the style of behavior responses or reactivity to routine sensory experiences (Dunn, 2007, 2014). These

sensory processing behavior patterns are:

• Sensory Registration. Sensory registration (e.g., high sensory neurological threshold and passive

self-regulatory behavior responses) is passive self-regulation behavior in which the individual may

not notice sensory cues that others can attend to easily (Dunn, 2014).

• Sensory Seeking. Sensory seeking (e.g., high sensory neurological threshold and active self-

regulatory behavior responses) is an active self-regulation behavioral strategy with which the

individual is driven to increase engagement in sensory experiences (Dunn, 2014).

• Sensory Sensitivity. Sensory sensitivity (e.g., low sensory neurological threshold and passive self-

regulatory behavior responses) is a passive self-regulation behavior strategy with which the

individual attends or responds quickly to sensory experiences (Dunn, 2014).

• Sensory Avoiding. Sensory avoiding (e.g., low sensory neurological threshold and active self-

regulatory behavior responses) is an active self-regulation behavioral strategy with which the

individual becomes anxious or bothered by sensory experiences and may be driven to avoid

sensory experiences (Dunn, 2014).

Literature Review

Research has shown that low sensory neurological threshold responses (i.e., increased reactivity

to sensory experiences) can be related to an inability to pay attention and can result in higher distractibility

(Bundy et al., 2007; Chien et al., 2016). Generally, children with high sensory neurological thresholds

(i.e., reduced reactivity to sensory experiences) respond to fewer stimuli than children with low sensory

thresholds (Dunn, 2014).

Research suggests that relationships exist between sensory behavioral reactivity, effortful control,

and behavioral self-regulation among children, especially those with challenges in inhibitory control

(Diamant, 2011; Gouze et al., 2012). Since inhibitory control is a component of executive function

(Diamond, 2013), the temperament characteristic of effortful control has the potential to support executive

function through the facilitation of attention, focus, and inhibitory control (Johnson, 2012; Nakagawa et

al., 2016). Supportive environments and parenting strategies for children with negative emotionality in

temperament and fearfulness have been found to encourage the development of successful socialization

2

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

(Kochanska et al., 2007). Understanding the relationships between sensory processing behaviors, the

temperament characteristic of effortful control, and abilities related to executive function may allow for

the development of supportive strategies that promote self-regulation, successful activity engagement, and

problem-solving. These supportive strategies could include management of the sensory attributes of the

context to promote successful task participation, engagement, and completion of daily occupations for

children.

Purpose of the Study

This study’s purpose was to examine the extent to which relationships exist between the

temperament characteristic of effortful control, executive function, and descriptive features of sensory

processing behaviors in school-aged children between 7.0 and 10.11 years of age. This study hypothesized

that statistically significant relationships exist between sensory processing behaviors, executive function,

and the temperament characteristic of effortful control in school-aged children between 7.0 and 10.11

years of age when physiological factors that may influence the reception of sensory input are minimized.

Method

This study’s research design used a non-experimental, descriptive correlation format to examine

the relationships between the parameters under investigation (i.e., temperament effortful control,

executive function, and sensory processing behaviors). The A. T. Still University Institutional Review

Board approved this study in May 2018.

Participants

Participants were parents or primary caregivers of school-aged children between 7.0 and 10.11

years of age. Criteria for inclusion were: healthy adults; 19 years of age or older; does not take medications

that may impact the responses on the questionnaires; are the primary caregiver of a healthy child between

7.0 and 10.11 years of age; and has no history of un-correctable sensory-neural hearing loss, un-correctable

visual impairment, or a medical condition that would require the regular use of medications that may

influence behavior. Data from parents, primary caregivers, or their children who do not meet the inclusion

criteria were excluded. Participants were recruited through the use of flyers and snowball sampling.

Instruments

Three standardized questionnaires were used to collect data regarding effortful control, executive

function, and sensory processing behaviors.

Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire

The temperament characteristic of effortful control was measured by the Temperament in Middle

Childhood Questionnaire (version 3.0) (TMCQ), a parent-report, standardized 157-item questionnaire for

children between 7.0 and 10.11 years of age (Simonds & Rothbart, 2004). Responses to the TMCQ reflect

the child’s temperament behavior in relation to everyday situations. Studies of psychometric properties

report adequate internal consistency (α >.70) for all temperament subscales, with the exception of

activation control (α = 0.64) and supported convergent validity (Kotelnikova et al., 2016; Nystrom &

Bengtsson, 2017).

Factor analysis of the 16 subcategories of temperament characteristics of the TMCQ resulted in

four major factors labeled as negative affect, effortful control, surgency, and sociability. Temperament

subcategories of the TMCQ that compile the major factor of effortful control were attention/focusing,

inhibitory control, low-intensity pleasure, perceptual sensitivity, and activation control.

3

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

The participants rated their child’s behavior on a 5-point Likert scale. Scaled scores are created

for each subcategory and major temperament characteristic. Scores that approach five indicate a higher

expression of that temperament characteristic.

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-2

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

, second edition (BRIEF

2), a parent-

report, standardized, 63-item questionnaire for children between 5 and 18 years of age (Gioia et al., 2015),

was used to assess executive function in relation to everyday situations. Reports of internal consistency

of all the subtests were within acceptable ranges (α >.80), as was test-retest reliability (> 0.82). Concurrent

validity studies indicate that the BRIEF

2 can demonstrate significant differences between children with

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and a control group of typically developing children. The

BRIEF

2 demonstrates strong construct validity with other tools of executive function.

Nine subcategories and three major indexes of executive function behaviors are measured by the

BRIEF

2 (see Appendix A). The participants rate their child’s behavior as never, sometimes, or often.

Responses are numerically coded and converted to raw scores and T-scores. Higher scores (i.e., T-scores

of 70 or above) indicate dysfunctional abilities in that category of executive function, whereas lower scores

(i.e., T-scores of 60 or below) indicate typical abilities in the described category of executive function.

Sensory Profile-2

The Sensory Profile-2 (SP-2) (Dunn, 2014), an 86-item, parent-report standardized questionnaire

for children between 3 and 14.11 years of age, was used to describe the style of behavior reactivity to

sensory experiences routinely experienced in everyday activities. Internal consistency, test-retest

reliability, and inter-rater reliability of the SP-2 are within acceptable ranges. Validity studies indicate that

significant differences exist in sensory-based behaviors between typically developing matched peers and

diagnostic groups of children with ADHD, autism, or dual diagnosis of ADHD and autism (Dunn, 2014).

The SP-2 describes sensory-based behaviors as four major quadrant factors (i.e., sensory

registration, sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoiding) and nine sensory-behavioral

subtests. Scores can be interpreted as sensory-based behaviors that are “just like the majority of others,”

“more or much more than others,” and “less or much less than others.” Higher scores indicate sensory-

based behaviors that are “more or much more than others.”

Data Collection and Analysis

The participants completed a packet of three standardized questionnaires and returned packets to

the researchers by mail in a pre addressed, stamped envelope. Descriptive statistics and Spearman’s R

correlation were used to analyze relationships between effortful control, executive function, and sensory-

processing behaviors using the data from the standardized questionnaires. SPSS ver. 23 (IBM Corp,

Armonk, NY) statistical package was used to analyze the data. A p-value of < .05 was used to test for

significance.

Results

Thirty-seven packets were delivered to potential participants. Twenty-three packets were returned,

and of those 23 packets, 19 were usable, leaving a sample size of N = 19 and an overall response rate of

51%.

Participants

The children in the sample were the following ages: 7 to 7.11 = five; 8 to 8.11 = seven; 9 to 9.11

= four; 10 to 10.11 = three. They were enrolled in the following grade levels: 1st = one; 2nd = eight; 3rd

= four; 4th = four; 5th = two). Thirteen of the children in the sample were male (68%), and six were female

4

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

(32%). Thirteen of the children in the sample were white (68%), and six were Hispanic (32%). The

caregivers in the sample were the following ages: 19 to 29 = two; 30 to 39 = eight; 40 to 49 = eight; 50 to

59 = one. Nine of the caregivers had education beyond the baccalaureate level; seven had 4 years of

college, while one caregiver had each, some high school, some college, or community college. Eleven of

the caregivers reported income greater than $75,000, while seven of the caregivers reported incomes

between $40,000 and $60,000. One caregiver reported an income between $60,000 and $75,000.

The descriptive characteristics of each assessment measure indicated that all components of the

SP-2 were found to score in the range of “just like the majority of others.” The participants’ mean scores

for the BRIEF

2 all fell in the “typical function” range with the exception of the Global Executive

Composite Index, whose mean score indicated a “clinically significant difference.” The total mean scaled

score for all 20 components of the TMCQ was 3.24 on a scale of 1 to 5. Scores that fall closer to five

indicate a stronger behavioral influence of that particular temperament characteristic. See Appendix A and

B for information about descriptive outcomes from assessment measures.

Higher raw scores for the SP-2 equate to the presence of behavior responses that are more than or

much more than others, which indicates increased reactivity to sensory experiences. Mid-range raw scores

on the SP-2 can equate to typical responses to stimuli, while raw scores that are very low indicate behavior

responses that are less than or much less than others (i.e., decreased reactivity). The BRIEF

2 measures

areas of executive function associated with executive function in relation to everyday situations that

involve behavioral regulation, emotional regulation, and cognitive regulation. Higher scores for the

BRIEF

2 indicate increased dysfunction in the specific area of executive function, whereas lower scores

indicate typical executive function. The TMCQ measures temperament behavior in the constructs of

negative affect, effortful control, surgency, and sociability. Higher scores for the TMCQ indicate increased

behavioral expression of the specific temperament characteristic. Examination of effortful control in

relation to sensory-based behaviors and executive function was the primary focus of the correlation

analyses.

Results of Correlation Analysis

Spearman’s R correlation statistical analyses were used to examine the extent to which statistically

significant relationships existed between effortful control and subcategories, the four main categories for

sensory-processing behaviors and subcategories, and the major composite categories for executive

function and subcategories. Statistically significant positive and negative correlations at or less than a p-

value of < .05 were found.

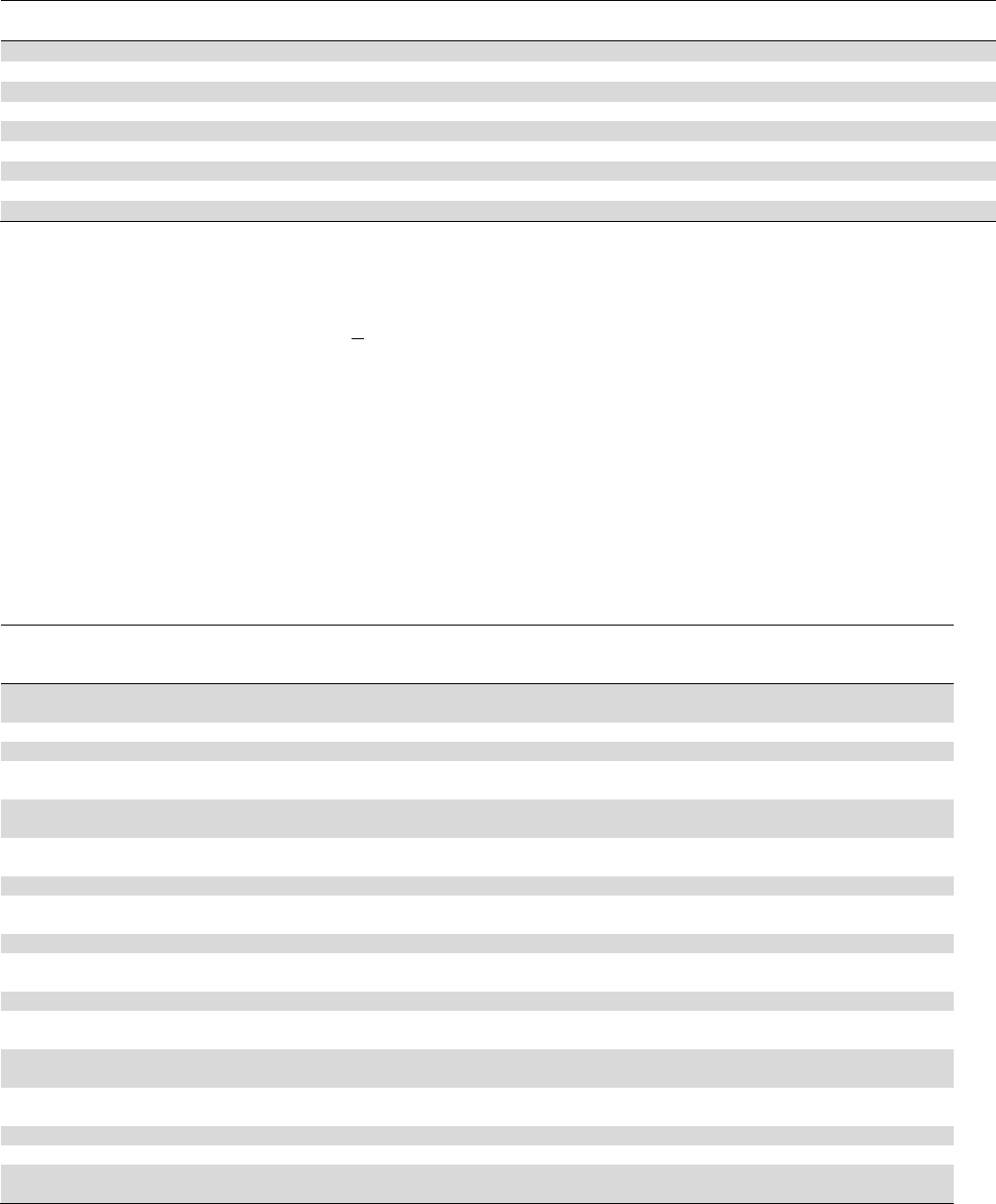

Statistically significant positive correlations were found between the BRIEF

2 and SP-2 main

categories and subcategories. These positive correlations indicate that high scores for the BRIEF

2 (i.e.,

greater dysfunction) are associated with higher scores on the SP-2, which indicate a more reactive sensory

response (i.e., “more than or much more than others”). Whereas low scores for the BRIEF

2 indicate

typical behavioral abilities for executive function and are associated with lower scores on the SP-2, which

indicate less sensory reactivity. Of note, only statistically significant positive correlations were found

between the BRIEF

2 and the SP-2; no negative correlations were found. Table 1 displays the statistically

significant positive correlations at p < .05 between the SP-2 sensory sensitivity and BRIEF

2 Behavioral

Regulation Index, Emotional Regulation Index, Global Executive Composite Regulation, and positive

correlations between the SP-2 sensory seeker and BRIEF

2 Behavioral Regulation Index, and the SP-2

sensory registration and the BRIEF

2 Cognitive Regulation Index.

5

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

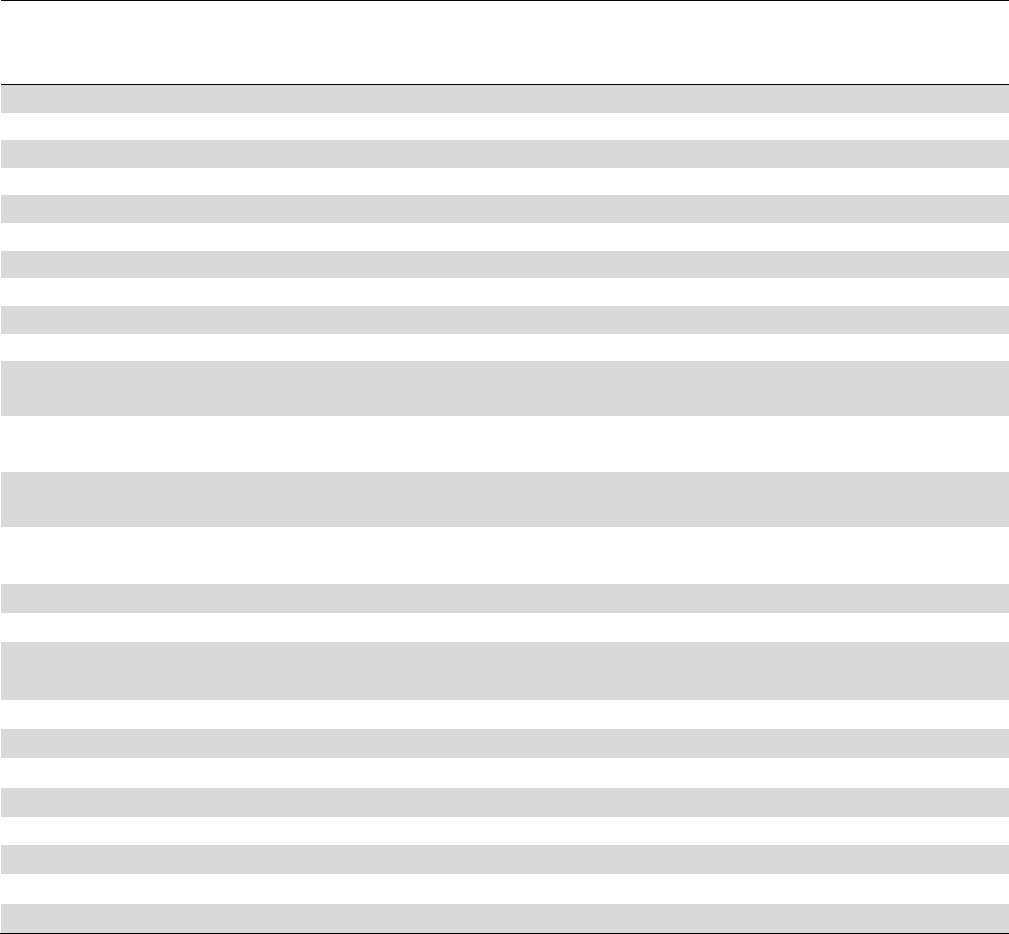

Table 1

Correlations using Spearman’s R Between the Main Quadrants from the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

(BRIEF

2) and the Main Quadrants from the Sensory Profile-2 (SP-2) (N = 19)

BRIEF

2: Behavioral

Regulation Index

(BRI)

BRIEF

2: Emotional

Regulation Index

(ERI)

BRIEF

2: Cognitive

Regulation Index

(CRI)

BRIEF

2: Global Executive

Composite Regulation Index

(GEC)

SP-2: Sensory

Seeker

.538*

0.089

0.222

0.445

SP-2: Sensory

Avoider

0.336

0.393

0.054

0.331

SP-2: Sensory

Sensitivity

.537*

.534*

0.219

.533*

SP-2: Sensory

Registration

0.375

-0.013

.531*

0.405

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

As illustrated in Table 2, statistically significant negative correlations at p < .05 were found

between TMCQ effortful control and the main categories BRIEF

2. These findings suggest that a strong

presence for the temperament ability for effortful control (i.e., higher scores on the TMCQ) is related to

typical skills for executive function (i.e., lower scores that indicate typical executive function according

to the BRIEF

2). Conversely, the reduced ability for effortful control is associated with challenges in

executive function. Statistically significant negative correlations at p < .05 were also found between

TMCQ effortful control and the sensory behavior of sensory seekers. This finding suggests that a reduced

ability for effortful control (i.e., lower scores on the TMCQ) is associated with increased sensory-seeking

behaviors that are “more or much more than others,” whereas a strong presence of temperament effortful

control (i.e., higher scores on the TMCQ) is related to the expression of sensory seeking behaviors that

are “just like” or “less than” others.

Table 2

Correlations using Spearman’s R Between the Main Variables for Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire (TMCQ)

and the Main Quadrants from the Sensory Profile-2 (SP-2) and the Main Quadrants from the Behavior Rating Inventory of

Executive Function (BRIEF

2) (N = 19)

TMCQ

Surgency

TMCQ

Effortful Control

TMCQ

Negative Affect

SP-2: Sensory Seeker

0.119

-.504*

0.104

SP-2: Sensory Avoider

0.160

-0.318

0.256

SP-2: Sensory Sensitivity

0.094

-0.345

-0.078

SP-2: Sensory Registration

0.257

-0.221

-0.072

BRIEF

2: Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI)

0.297

-0.294

-0.223

BRIEF

2: Emotional Regulation Index (ERI)

0.125

-0.040

0.449

BRIEF

2: Cognitive Regulation Index (CRI)

0.382

-.511*

-0.200

BRIEF

2: Global Executive Composite Regulation Index (GEC)

0.393

-.551*

-0.123

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 3 presents the correlations between the BRIEF

2 executive function subcategories and the

SP-2 sensory processing subcategories. Results demonstrated statistically significant positive correlations

at p < .05, especially between auditory, movement and conduct subcategories on the SP-2 and the inhibit,

self-monitor, emotional control and initiate subcategories on the BRIEF

2. Again, no significant negative

correlations were found between the BRIEF

2 executive function subcategories and the SP-2 sensory

processing subcategories.

6

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

Table 3

Correlations using Spearman’s R between the Subcategories for the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

and the Subcategories from the Sensory Profile-2 (SP-2) (N = 19)

BRIEF

2:

Inhibit

BRIEF

2: Self-

Monitor

BRIEF

2:

Shift

BRIEF

2: Emotional

control

BRIEF

2:

Initiate

SP-2: Auditory

.589

**

.599

**

0.245

0.072

0.313

SP-2: Visual

0.079

0.095

0.285

0.222

0.079

SP-2: Touch

0.348

0.349

-0.065

-0.326

0.022

SP-2: Movement

0.333

.536

*

0.073

-0.105

.477

*

SP-2: Body Position

0.196

0.240

-0.065

0.218

0.196

SP-2: Oral

0.186

0.133

-0.040

-0.386

-0.200

SP-2: Conduct

.506

*

.460

*

0.237

0.380

0.381

SP-2: Social Emotional

-0.036

0.151

0.294

.683

*

0.077

SP-2: Attention

.509

*

.465

*

0.254

0.389

0.375

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Analysis between the subcategories for the TMCQ and the SP-2 found both statistically significant

positive and negative correlations at p < .05 (see Table 4). The significant positive correlations were found

between the TMCQ subcategory of impulsivity and the SP-2 subcategories of movement, conduct, and

attention, which indicates that a greater tendency towards impulsive behavior is associated with “more or

much more than others” for reactivity toward vestibular experiences, and sensory-based issues in behavioral

conduct and inattention. Also noteworthy were the negative correlations between the Auditory subcategory

on the SP-2 and the TMCQ subcategories of fantasy/openness, inhibitory control, and perceptual sensitivity,

which infers that greater ability to regulate auditory sensory experiences is related to increased expression

of inhibitory control and perceptual awareness.

Table 4

Correlations using Spearman’s R Between the Subcategories for the TMCQ and the Subcategories from the SP-2 (N = 19)

SP-2:

Auditory

SP-2:

Visual

SP-2:

Touch

SP-2:

Movement

SP-2:

Body

Position

SP-2:

Oral

SP-2:

Conduct

SP-2: Social

Emotional

SP-2:

Attention

TMCQ- Activation

Control

-.349

.282

-.043

-.375

.000

-.013

-0.157

-.305

-.175

TMCQ- Activity Level

.015

-.472*

-.130

.151

-.346

-.026

0.220

-.167

.220

TMCQ- Affiliation

-.543*

-.094

.173

-.105

-.389

.106

-0.189

-.480*

-.205

TMCQ- Anger &

Frustration

.135

.283

-.324

-.063

.086

-.211

0.283

.367

.290

TMCQ- Assertive-

Dominance

.120

.110

-.195

-.046

.216

-.013

0.267

-.012

.283

TMCQ- Attention

Focusing

-.229

-.345

-.151

-.263

-.065

.303

-0.298

.052

-.287

TMCQ- Discomfort

-.150

.376

-.280

.201

-.216

-.224

.408

.497

*

.415

TMCQ- Fantasy-

Openness

-.543

*

-.157

-.130

-.166

-.345

.132

-.157

-.17

-.178

TMCQ- Fear

-.224

-.157

-.259

-.119

-.302

-.158

.016

.275

.013

TMCQ- High-Intensity

Pleasure

.059

.078

.345

-.126

.086

-.040

.282

-.068

.285

TMCQ- Impulsive

.402

.298

.301

.518

*

.129

-.066

.470

*

-.174

.474

*

TMCQ- Inhibitory

Control

-.545

*

-.157

-.259

-.284

-.216

.053

-.188

.034

-.208

TMCQ- Low-Intensity

Pleasure

-.332

-.125

.280

-.295

-.215

.488

*

-.219

.016

-.237

TMCQ- Perceptual

Sensitivity

-.673

**

.000

.151

-.588

**

-.151

.277

-.157

-.203

-.176

TMCQ- Sadness

-.118

.047

-.216

-.202

-.086

-.132

.220

.633

**

.220

TMCQ- Shyness

-.043

.000

.130

-.338

.281

-.119

-.031

.364

-.040

TMCQ- Sooth-ability &

Falling Reactivity

.080

-.219

.086

0.013

-.108

.277

-.282

-.580

**

-.293

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

7

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

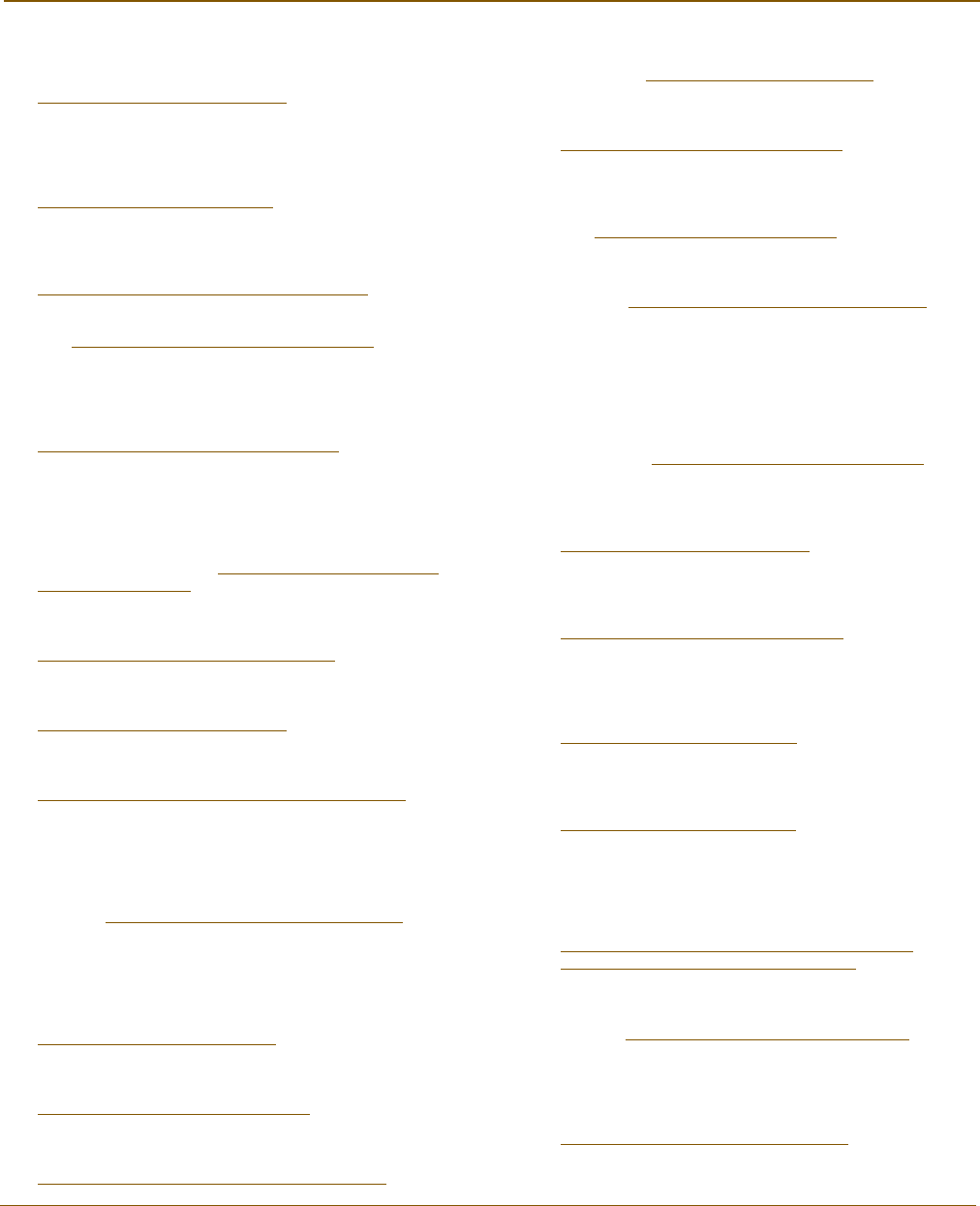

Analysis between the subcategories for the TMCQ and the BRIEF

2 found both statistically significant positive and

negative correlations at p < .05 (see Table 5). Several significant negative correlations were found between the subcategory of

attention/focusing on the TMCQ and the BRIEF

2 subcategories of initiate, working memory, plan/organize, task-monitor,

and organization of materials, which indicates that increased ability to attend/focus (i.e., higher scores on the TMCQ) is

associated with typical executive function (i.e., lower scores on the BRIEF

2). Of interest is that statistically significant positive

correlations were found between the BRIEF

2 subcategory of inhibit and the TMCQ subcategories of high-intensity pleasure

and impulsivity, as well as between the TMCQ subcategories of anger/frustration, assertiveness/dominance, high-intensity

pleasure, impulsivity, discomfort, sadness and shyness and the BRIEF

2 subcategories of shift, emotional control and inhibit.

These findings indicate that increased expressions of these temperament subcategory traits (i.e., higher scores on the TMCQ)

are associated with atypical executive function abilities to shift attention, self-inhibit, and emotional self-control (i.e., higher

scores that indicate dysfunction according to the BRIEF

2).

Table 5

Correlations using Spearman’s R Between the Subcategories for TMCQ and the Subcategories Categories for the BRIEF

(N = 19)

BRIEF

2

Inhibit

BRIEF

2

Self-

Monitor

BRIEF

2

Shift

BRIEF

2:

Emotional

Control

BRIEF

2:

Initiate

BRIEF

2:

Working

Memory

BRIEF

2:

Plan &

Organize

BRIEF

2:

Task

Monitor

BRIEF

2:

Organization

of Materials

TMCQ

Activation

Control

-.106

-.363

-.280

-.294

-.518

*

-.080

-.471

*

-.006

.081

TMCQ-

Activity

Level

.264

.080

-.057

-.268

.248

.144

.137

.396

.110

TMCQ

Affiliation

-.096

-.439

-.240

-.434

-.296

-.015

-.218

-.146

-.002

TMCQ

Anger &

Frustration

-.094

-.037

.759

**

.684

**

.151

-.100

.117

.053

-.038

TMCQ

Assertive-

Dominance

.194

-.187

.474

*

.354

-.318

-.258

-.133

.000

.147

TMCQ

Attention

Focusing

-.401

-.205

-.035

.129

-.662

**

-.732

**

-.692

**

-.520

*

-.460

*

MCQ

Discomfort

-.162

-.101

.558

*

.637

**

-.038

-.334

.030

-.273

-.246

TMCQ

Fantasy-

Openness

-.528

*

-.573

*

-.356

-.320

-.337

-.273

-.492

*

-.251

-.286

TMCQ

Fear

-.459

*

-.386

.287

.338

-.221

-.563

*

-.257

-.265

-.502

*

TMCQ

High-

Intensity

Pleasure

.459

*

.032

-.113

-.145

.099

.226

.283

.245

.416

TMCQ

Impulsive

.459

*

.032

-.113

-.145

.099

.226

.283

.245

.416

TMCQ

Inhibitory

Control

-.654

**

-.557

*

-.248

-.045

-.362

-.362

-.624

**

-.293

-.470

*

TMCQ

Low-

Intensity

Pleasure

-.272

-.113

.004

-.045

-.367

-.218

-.524

*

-.374

-.414

TMCQ

Perceptual

Sensitivity

-.183

-.406

.110

.036

-.349

-.080

-.488

*

-.277

-.030

TMCQ

Sadness

-.254

-.031

.603

**

.833

**

.044

-.301

.051

-.268

-.276

TMCQ

Shyness

-.244

-.015

.224

.555

*

.066

-.145

-.019

-.132

-.229

TMCQ

Sooth-

ability &

Falling

Reactivity

.124

-.063

-.481

*

-.791

**

-.180

.214

-.195

.297

.184

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

8

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

Discussion

Various positive and negative correlations were identified between the main categories and

subcategories from the BRIEF

2, TMCQ, and SP-2, and indicate that behaviors related to effortful

control, sensory processing, and executive function are interrelated. Interpretation of positive correlations

suggests that increased behavioral reactivity to sensory input is related to greater issues and dysfunction

in executive function, whereas more typical reactions to sensory input are related to more typical executive

function. For example, the positive correlation between the sensory seeker category on the SP-2 and the

Behavioral Regulation Index on the BRIEF

2 indicates that the demonstration of increased sensory-

seeking behaviors is associated with increased challenges in executive function for behavioral regulation.

Conversely, typical sensory-seeking behaviors are associated with executive function for typical

behavioral regulation. Positive correlations between the BRIEF

2 Cognitive Regulation Index and the SP-

2 sensory registration category suggest that the ability to problem solve, learn, and recall complex

information is associated with the ability to attend to sensory cues in the environment appropriately. These

findings are supported by prior research that explored relationships between temperament, sensory

reactivity, and behavioral regulation in activity engagement (DeSantis et al., 2011; Gouze et al., 2012).

Of note, significant positive correlations exist between auditory, movement, and conduct

subcategories on the SP-2 and the inhibit, self-monitor, emotional control, and initiate subcategories on

the BRIEF

2. These outcomes indicate that less reactive responses to auditory, vestibular, and sensory-

related emotional conduct are more likely to be associated with typical executive function for the abilities

to inhibit and/or initiate one’s behavior and self-monitor/control one’s emotions, whereas more reactive

sensory responses in these areas are related to more dysfunctional abilities for these executive functions.

Positive correlations were found between the TMCQ subcategory of impulsivity and the SP-2

subcategories of movement, conduct, and attention, which indicate that stronger tendencies toward

impulsivity are associated with increased sensory reactivity to vestibular input and sensory-based

responses that impact conduct and attention. Conversely, reduced tendencies toward impulsive

temperament behavior are associated with typical or less reactive sensory responses to vestibular input,

conduct, and attention. Because reduced tendencies toward impulsive temperament behavior are a

component of effortful control and abilities for behavioral self-regulation, the ability to demonstrate less

reactive sensory responses may support abilities for effortful control. Considering prior research that

relates the role of low abilities for effortful control and decreased self-regulation with social-emotional

issues in childhood (Nigg, 2017; Zentner et al., 2021), the associations between sensory-based behaviors

and effortful control warrant further evaluation. For instance, the role of sensory-based behaviors may

have played a part in the outcomes of research by Kochanska et al. (2007) that reported the positive impact

of supportive environments on the development of successful socialization in children.

Statistically significant negative correlations were found between the TMCQ subcategories of

affiliation, activity level, fantasy/openness, inhibitory control, perceptual sensitivity, and

soothability/falling reactivity and the SP-2 subcategories of auditory, movement, visual, and social-

emotional sensory reactivity. These findings suggest that increased reactivity toward visual, vestibular,

auditory input, and social-emotional sensory reactivity are associated with a reduced ability for

temperament inhibitory control, perceptual sensitivity, and reduced ability to self-soothe, which are all

components for effortful control. Similarly, negative correlations were found between subcategories on

the BRIEF

2 for task initiation, working memory, task planning/organizing, monitoring, organization of

material, inhibition, shift, and emotional control, and the TMCQ subcategories for activation control,

9

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

attention focusing, fantasy/openness, fear, inhibitory control, soothing/falling reactivity, low-intensity

pleasure, and perceptual sensitivity. These findings suggest that typical executive functions for task

organization, planning, initiation, attention shifting, and working memory are associated with a stronger

expression of temperament abilities related to attention, inhibitory control, and activity focus (i.e., effortful

control). This finding is supported by outcomes of research that reported relationships between emotional

and behavioral self-regulation and educational achievement in school-aged children (Edossa et al., 2018)

and outcomes of cognitive and self-regulatory abilities during adolescence (Zentner & Bates, 2008).

Again, the inter-relationships between effortful control and executive function that could be influenced by

sensory-based behaviors need to be considered.

Finally, statistically significant negative correlations between the auditory subcategory on the SP-

2 and the TMCQ subcategories of inhibitory control and perceptual sensitivity (components of effortful

control) suggest that reactivity toward auditory input is related to effortful control. One can infer the ability

to process auditory information without being over-reactive is associated with the ability to effectively

process information, regulate emotions, concentrate, and problem-solve without being distracted by

auditory input. Zentner and Bates (2008) report that sensory sensitivity, especially tactile, visual, and

auditory sensitivity, is a dimension of temperament that warrants more research. The outcomes of this

study support the need to consider the influence of sensory-based behaviors as they relate to effortful

control and executive function.

Limitations

Although the assessments were all standardized, the potential for self-report bias could be a

limitation. Perhaps the ability to interview participants during data collection would reduce the possibility

of self-report bias or possible misinterpretation of assessment questions and could have yielded a larger

sample size.

Conclusion

Relationships exist between sensory processing behaviors, temperament characteristics for

effortful control, and executive functioning. Findings indicate that increased sensory reactivity is related

to greater issues/dysfunction in executive function and effortful control, whereas more typical responses

to sensory experiences are related to more typical abilities for executive function and stronger behavioral

self-regulation abilities for effortful control.

Addressing sensory responsiveness/reactivity in the context may support behavior management for

effortful control and executive function.

Occupational therapists are able to design strategies that support an individual’s ability for task

engagement and participation. Outcomes from this study promote the awareness of the interrelationships

between effortful control, sensory processing behaviors, executive function, and the potential for the use

of sensory strategies as a support for behavioral self-regulation that fosters executive function.

Temperament-based intervention (i.e., awareness of temperament styles and contextual goodness of fit)

in the context of parenting and school environments can support children who are challenged by decreased

behavioral inhibition and inattentiveness (McClowry et al., 2008; Zentner & Bates, 2008). By evaluating

a child’s sensory-based responses and the sensory attributes of the context, occupational therapists can

supplement temperament-based intervention strategies. For example, a child who is easily distracted and

agitated by auditory stimuli in a noisy environment may be able to improve effortful control to focus on

executive function for task completion through the use of headphones. Or, a child who seeks tactile and

vestibular sensory experiences to the point of distraction or impulsivity may present with improved

10

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

attention and self-regulation when provided with context-appropriate opportunities for extra tactile and

movement experiences (i.e., appropriate tactile fidget toys or an inflatable seat cushion for extra vestibular

input while seated at a desk). Future studies could address the effectiveness of supportive sensory

strategies in the behavioral management of self-regulation and executive function.

References

Bundy, A. C., Shia, S., Qi, L., & Miller, L. J. (2007). How does

sensory processing dysfunction affect play? American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 201–208.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.201

Caughy, M. O., Mills, B., Brinkley, D., & Owen, M. T. (2018).

Behavioral self-regulation, early academic achievement, and

the effectiveness of urban schools for low-income ethnic

minority children. American Journal of Community

Psychology, 61(3–4), 372–385.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12242

Chien, C-W., Rodger, S., Copley, J., Branjerdporn, G. , &

Taggart, C. (2016). Sensory processing and its relationship

with children’s daily life participation. Physical and

Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 36(1), 73–87.

https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2015.1040573

Critz, C., Blake, K., & Nogueira, E. (2015). Sensory challenges in

children. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 11(7), 710–

716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.04.016

DeSantis, A., Harkins, D., Tronick, E., Kaplan, E., & Beeghly, M.

(2011). Exploring an integrative model of infant behavior:

What is the relationship among temperament, sensory

processing, and neurobehavioral measures? Infant

Behavioral Development, 34(2), 280–292.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbhe.2011.01.003

Diamant, R. (2011). Exploration of the Relationships Between

Temperament and Sensory-Processing Behaviors in Parent-

Child Dyads (Publication No. 3458588) [Doctoral

dissertation, Northcentral University]. ProQuest Dissertations

Publishing.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review in

Psychology, 64, 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-

psych-113011-143750

Dixon Jr., W. E., Salley, B. J., & Clements, A. D., (2006).

Temperament, distraction, and learning in toddlerhood.

Infant Behavior and Development, 29, 342–357.

https://doi.org/10.1016j.infbeh.2006.01.002

Dunn, W. (2001). The sensations of everyday life: Empirical,

theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. American Journal

of Occupational Therapy, 55(6), 608–620.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.6.608

Dunn, W. (2007). Supporting children to participate successfully

in everyday life by using sensory processing knowledge.

Infants and Young Children, 20(2), 84–101.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.IYC.0000264477.05076.5d

Dunn, W. (2014). Sensory profile-2: User’s manual. Pearson

Psychological Corporation.

Edossa, A., Schroeders, U., Weinert, S., & Artelt, C. (2018). The

development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and

their effects on academic achievement in childhood.

International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(2),

192–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416687412

Gioia, G, Isquith, P., Guy, S., & Kenworthy, L. (2015). Behavior

Rating Inventory of Executive Function (2nd ed.). PAR.

Gouze, K., Lavigne, J., Hopkins, J., Bryant, F., & LeBailly, S.

(2012). The relationship between temperamental negative

affect, effortful control, and sensory regulation: A new look.

Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(6), 620–632.

https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21363

Henderson, H. A., & Wachs, T. D. (2007). Temperament theory

and the study of cognition-emotion interactions across

development. Developmental Review, 27(3), 396–427.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.06.004

Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences. (n.d.). Module 12:

Temperament in Early Childhood. Institute for Learning and

Brain Sciences. University of Washington.

https://modules.ilabs.uw.edu/module/temperament/

Janson, H., & Mathiesen, K. (2008). Temperament profiles from

infancy to middle childhood: Development and associations

with behavior problems. Developmental Psychology, 44 (5),

1314–1328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012713

Johnson, M. (2012). Executive function and developmental

disorders: The flip side of the coin. Trends in Cognitive

Sciences, 16(9), 454–457.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.07.001

Kotelnikova, Y., Olino, T. M., Klein, D. N., Kryski, K. R., &

Hayden, E. P. (2016). Higher- and lower-order factor

analyses of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire in early

and middle childhood. Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 92–

108. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000153

Kochanska, G., Aksan, N., & Joy, M. E. (2007). Children’s

fearfulness as a moderator of parenting in early socialization:

Two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 43(1),

222–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.222

McClelland, M. M., Ponitz, C. C., Messersmith, E. E., &

Tominey, S. (2010). Self-regulation: Integration of cognition

and emotion. In W. F. Overton & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), The

handbook of life-span development (1st ed., pp. 509–555).

Wiley.

McClowry, S. C., Rodriguez, E, & Koslowitz, R. (2008).

Temperament-based intervention: Re-examining goodness-

of-fit. International Journal of Developmental Science, 2(1–

2), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.3233/dev-2008-21208

Miller, L. J., Anzalone, M. E., Lane, S. J., Cermak, S. A., &

Osten, E. T. (2007). Concept evolution in sensory

integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 135–140.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.135

Nakagawa, A., Sukigara, M., Miyachi, T., & Nakai, A. (2016).

Relations between temperament, sensory processing, and

motor coordination in 3-year-old children. Frontiers In

Psychology, 7, Article 623.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00623

Nigg, J. T. (2017). On the relations among self-regulation, self-

control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive

control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for

developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 361–383.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12675

Nystrom, B., & Bengtsson, H. (2017). A psychometric evaluation

of the Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire

(TMCQ) in a Swedish sample. Scandinavian Journal of

Psychology, 58(6), 477–484.

https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12393

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In W.

Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of

child psychology : Social, emotional, and personality

development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). Wiley.

Simonds, J., & Rothbart, M. (n.d.). Temperament in middle

childhood questionnaire (TMCQ) (version 3.0).

https://research.bowdoin.edu/rothbart-temperament-questionnaires/instrument-

descriptions/the-temperament-in-middle-childhood-questionnaire/

Zentner, M., & Bates, J. E. (2008). Child temperament: An

integrative review of concepts, research programs, and

measures. European Journal of Developmental Science, 2(1–

2), 7–37. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-2008-21203

Zentner, M., Biedermann, V., Tafernerm C., da Cudan, H.,

Mohler, E., Straub, H., & Sevecke, K.

(2021). Early detection of temperament risk factors: A comparison

of clinically referred and general population children.

Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 667503.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.667503

11

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

Dr. Rachel B. Diamant, PhD, OTR/L, BCP, is emeritus professor in occupational therapy for A. T. Still University in Mesa,

AZ. She has more than 40 years clinical and teaching experience in pediatric occupational therapy practice with young children

and their families. Dr. Diamant is co-author and illustrator of a book for therapists and families involved in early intervention

home programming entitled Positioning for Play: Enhancing Development Through Positioning, Movement, and Sensory

Exploration.

Dr. Natasha Smet, OTD, OTR/L, is an assistant clinical professor and hybrid program site coordinator for Northern Arizona

University in Phoenix, AZ. She has over 7 years of clinical and teaching experience in pediatric occupational therapy practice

of children and their families. Dr. Smet is an author and co-author of three textbook chapters in leading pediatric occupational

therapy textbooks and was recently named the co-editor of Pediatric Skills for Occupational Therapy Assistants textbook.

If you enjoyed this article and are able to give, please consider a contribution to

support OJOT’s mission of providing open-access to high quality articles that focus

on applied research, practice, education, and advocacy in the occupational therapy

profession. https://secure.wmualumni.org/s/give?funds=POJO

12

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164

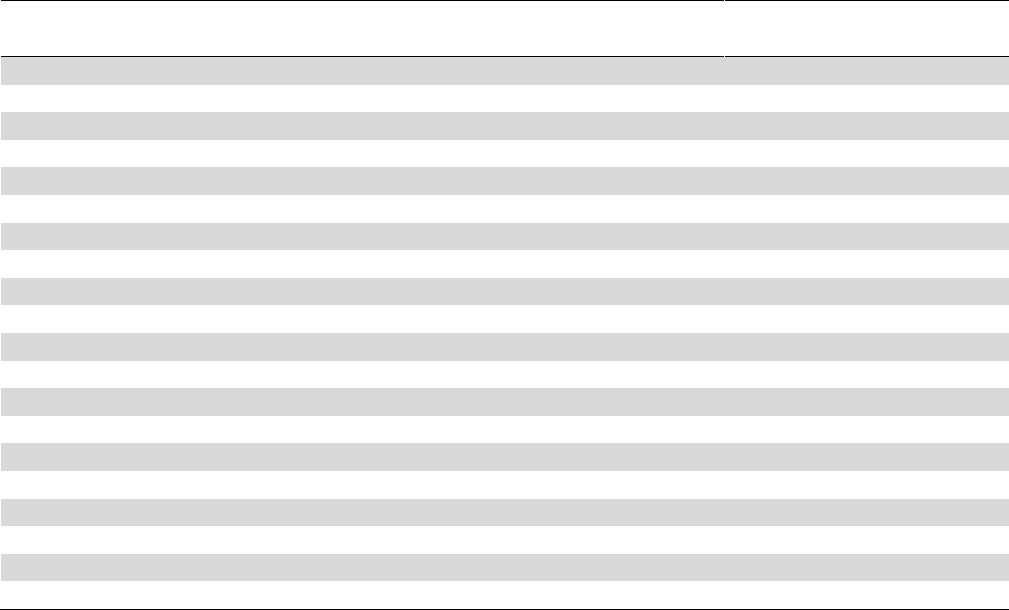

Appendix A

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants on the Sensory Profile-2 (SP-2) and the Behavior Rating

Inventory Executive Function-2 (BRIEF2

) (N = 19)

Assessment

Characteristics

Mean

(Raw

Scores)

Standard

Deviation

Score Interpretation

SP-2 Sensory Seeker Quadrant

32.45

+/-8.00

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Sensory Avoiding Quadrant

37.47

+/-14.21

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Sensory Sensitivity Quadrant

32.26

+/-8.44

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Sensory Registration Quadrant

31.11

+/-6.32

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Auditory Processing: Subtest

17.58

+/-6.58

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Visual Processing: Subtest

11.47

+/-2.49

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Touch Processing: Subtest

15.42

+/-6.29

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Movement Processing Subtest

11.63

+/-3.53

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Body Position Subtest

9.68

+/-2.34

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Oral-Sensory Subtest

16.79

+/-6.89

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Conduct in relation to sensory

processing: Subtest

15.26

+/-4.59

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Social Emotional Behavior

related to sensory processing: Subtest

27.32

+/-11.65

Just like the majority of others

SP-2 Attention Behavior related to

sensory processing: Subtest

16.63

+/-4.94

Just like the majority of others

BRIEF2

Behavioral Regulation

Index

22.32

+/-5.14

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Emotional Regulation Index

28.16

+/-9.37

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Cognitive Regulation Index

55.63

+/-12.00

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Global Executive

Composite

106.11

+/-20.72

Clinically Significant

Difference

BRIEF2

Inhibit Subtest

14.89

+/-3.59

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Self-Monitor Subtest

7.42

+/-2.04

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Shift Subtest

12.53

+/-2.97

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Emotional Control Subtest

13.79

+/-4.34

Typical Function

Initiate

8.53

+/-2.09

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Working Memory Subtest

13.63

+/-3.32

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Plan/Organize Subtest

13.47

+/-3.37

Typical Function

BRIEF2

Task/Monitor Subtest

8.53

+/-2.67

Typical Function

13

SENSORY PROCESSING, TEMPERAMENT, EXECUTIVE FUNCTION IN SCHOOL CHILDREN

Published by ScholarWorks at WMU, 2024

Appendix B

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants on the Temperament in Middle Childhood Questionnaire (N = 19)

Temperament Characteristic

Mean

(Scaled Scores)

Standard Deviation

Surgency Composite Score

3.33

+/-0.37

Effortful Control Composite Score

3.33

+/-0.54

Negative Affect Composite Score

2.77

+/-0.41

Activation Control

3.36

+/-0.48

Activity Level

4.07

+/-0.83

Affiliation

4.20

+/-0.63

Anger/Frustration

2.75

+/-0.75

Assertiveness/Dominance

3.67

+/-0.64

Attention Focusing

3.11

+/-0.99

Discomfort

2.61

+/-0.61

Fantasy/Openness

4.07

+/-0.51

Fear

2.54

+/-0.76

High-Intensity Pleasure

3.52

+/-0.73

Impulsivity

3.07

+/-0.67

Inhibitory Control

3.06

+/-0.85

Low-Intensity Pleasure

3.60

+/-0.56

Perceptual Sensitivity

3.09

+/-0.65

Sadness

2.69

+/-0.74

Shyness

2.747

+/-0.99

Soothability

3.28

+/-0.67

Note. On a scale of 1–5, scores that fall closer to 5 indicate a stronger behavioral influence of that temperament characteristic.

14

THE OPEN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY – OJOT.ORG

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol12/iss1/2

DOI: 10.15453/2168-6408.2164