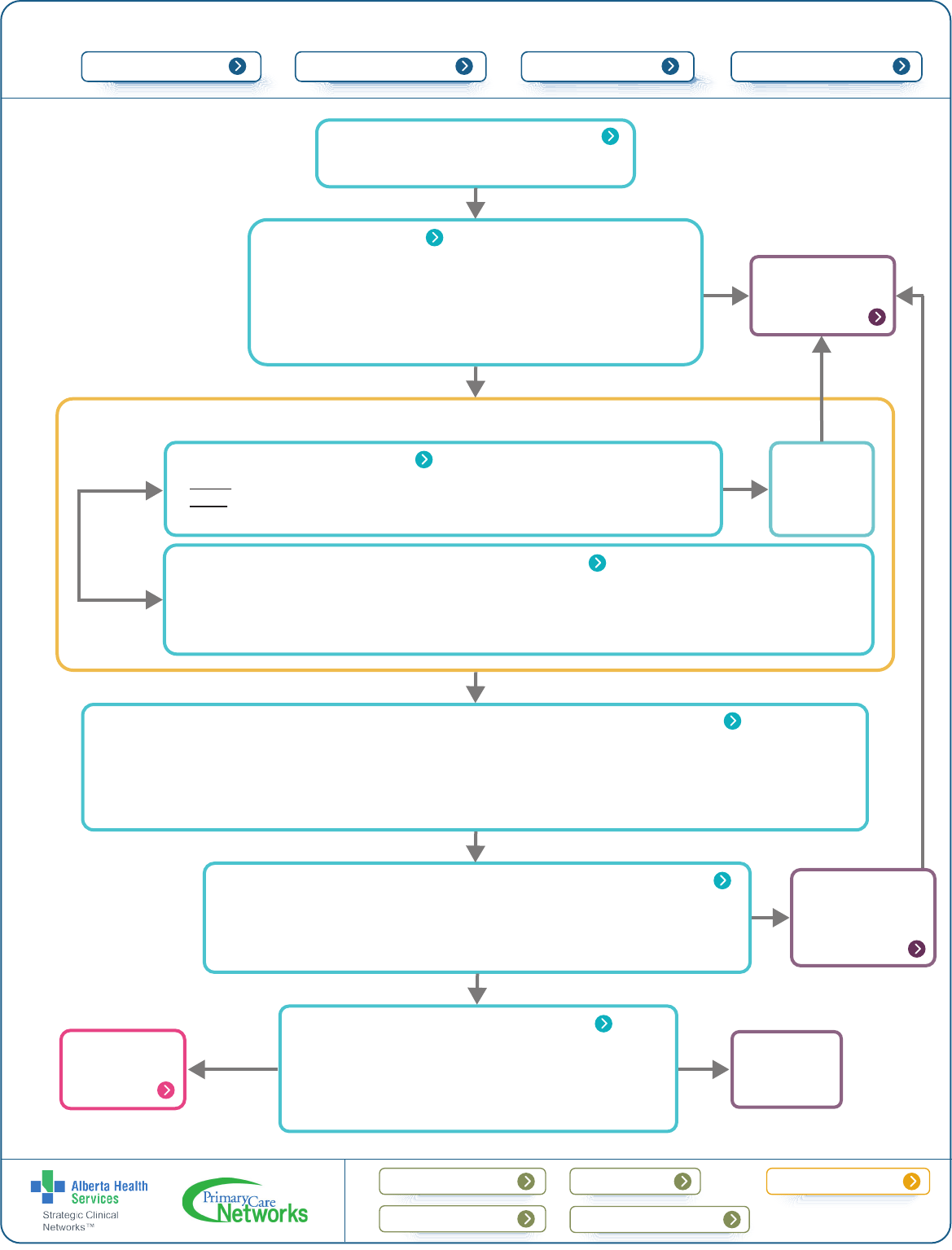

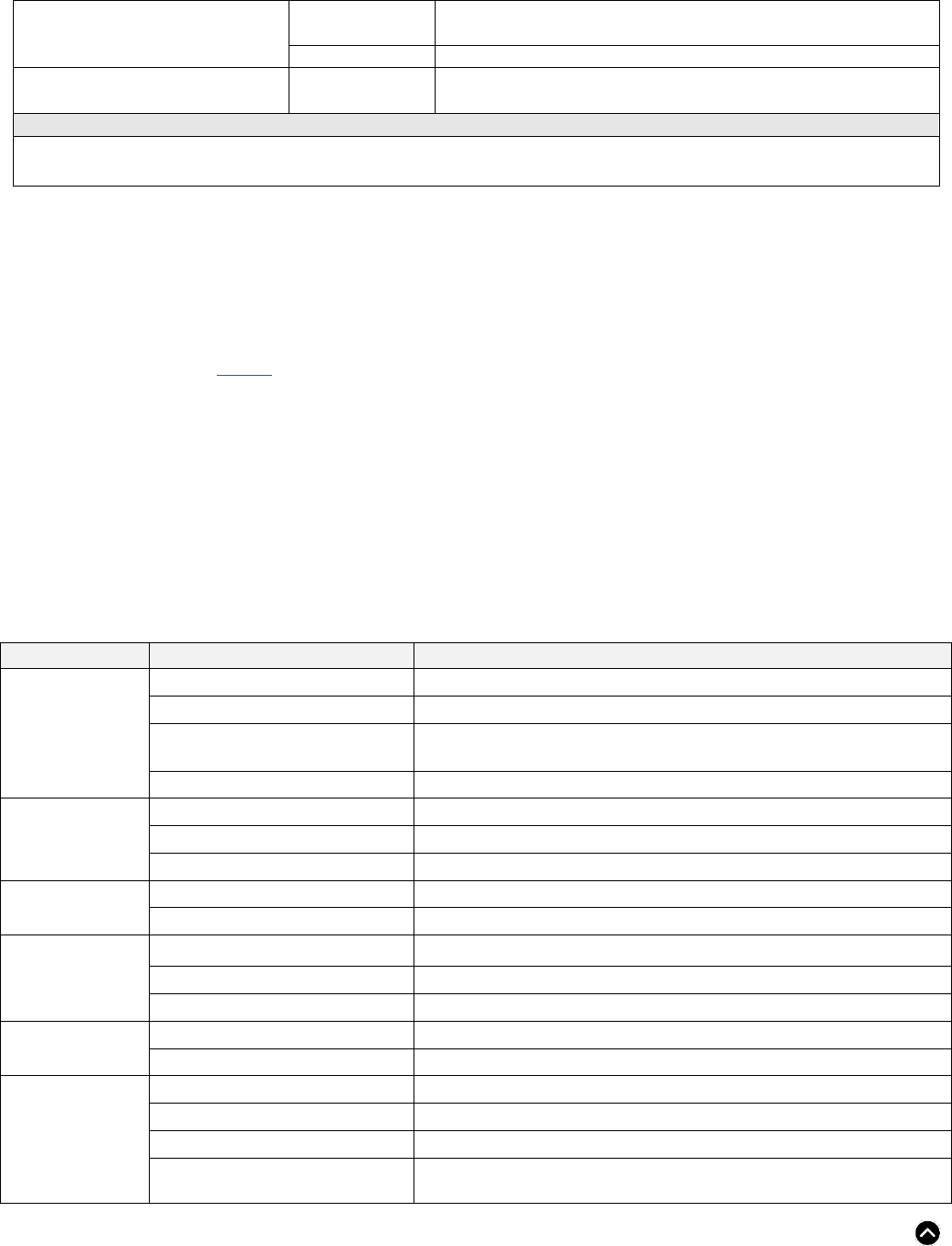

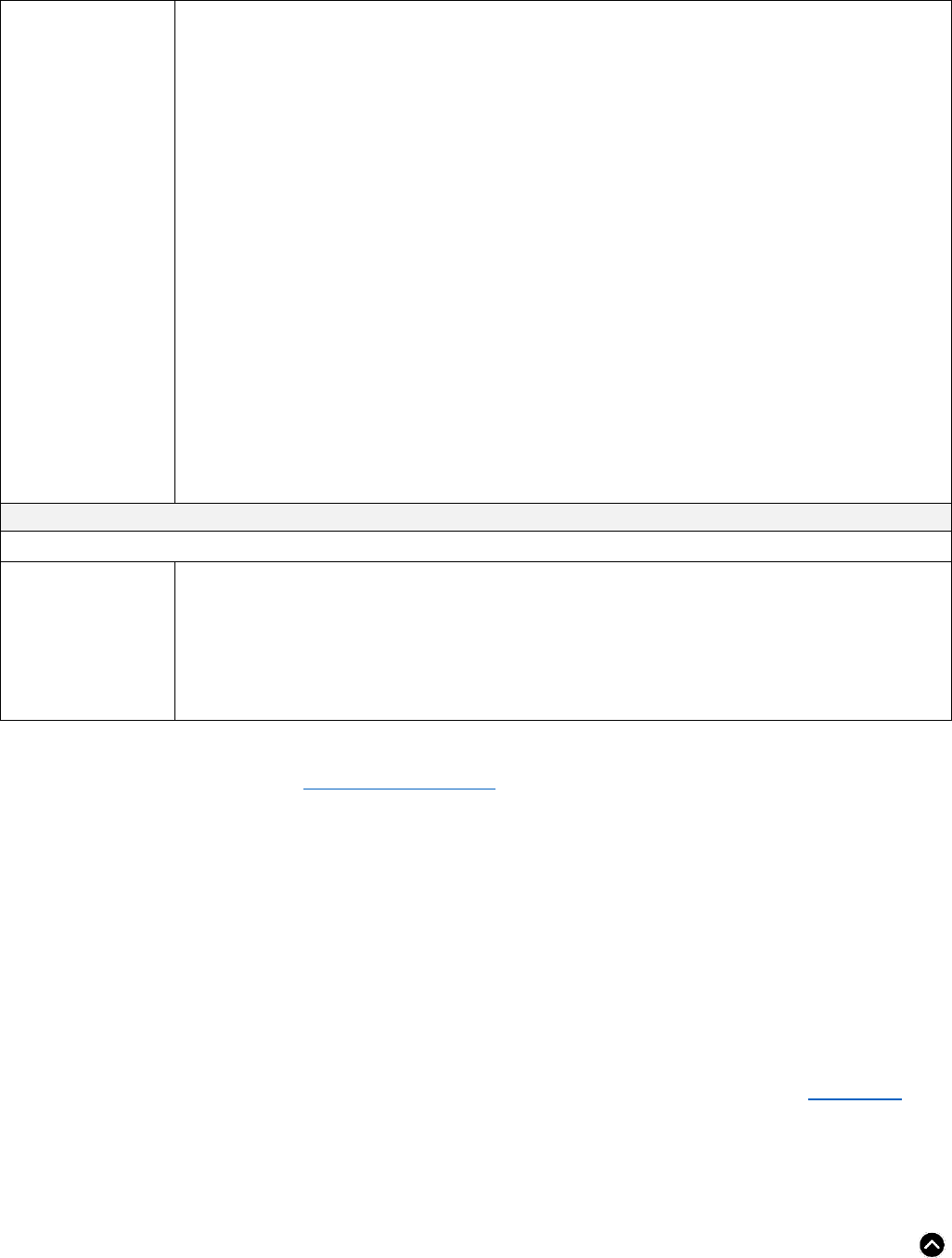

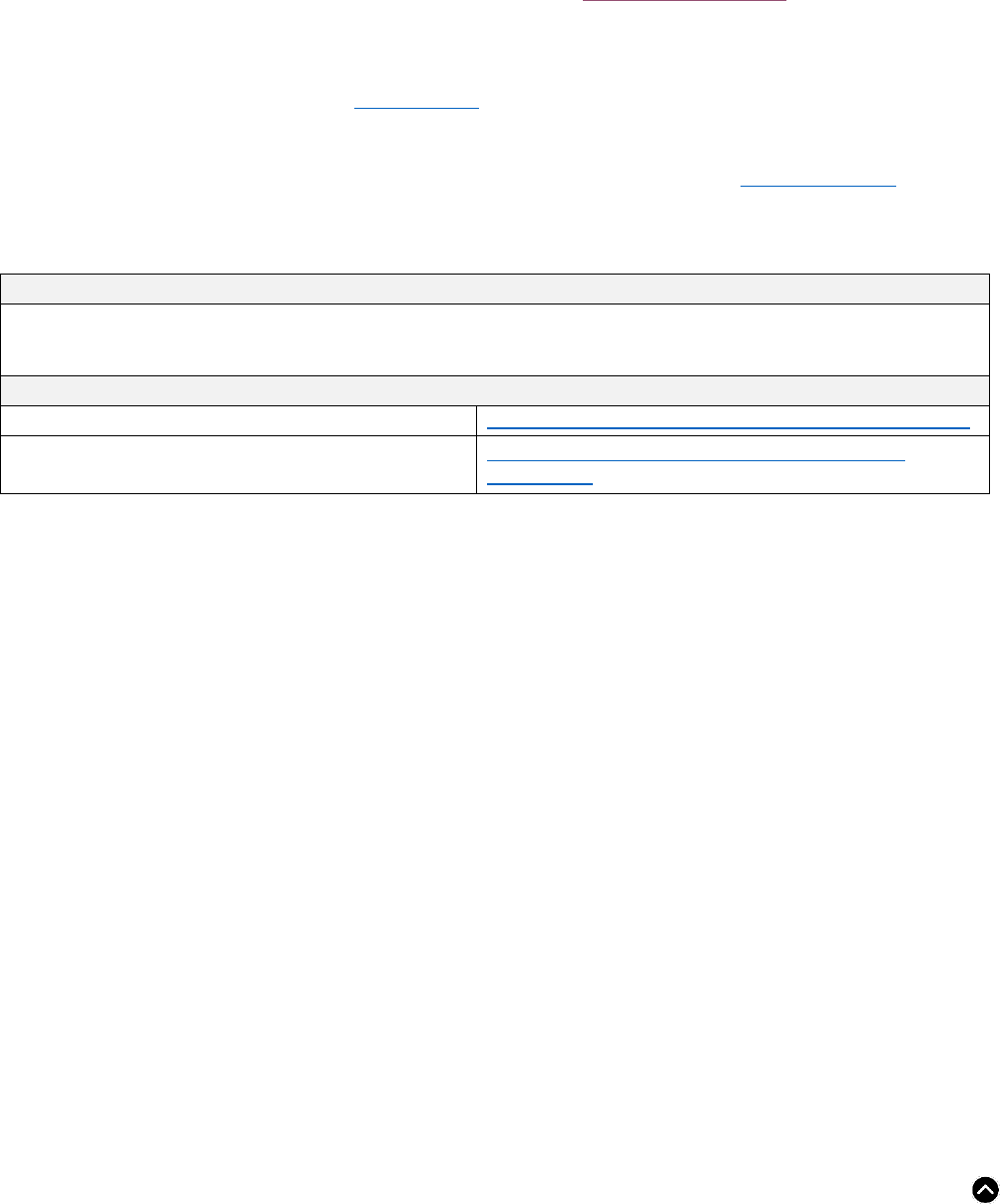

3. Baseline investigations

Chronic Diarrhea Primary Care Pathway

4. Optimize management of secondary causes

7. Consider alternative diagnoses

2. Alarm features

• Family history (first-degree relative) of IBD or colorectal cancer

• Onset of symptoms after age 50

• Unintended weight loss (> 5% over 6-12 months)

• Nocturnal symptoms or significant incontinence

• Visible blood in stool

• Iron deficiency anemia (see Iron Primer)

Yes

Initial investigation and management (dependent on history)

Consider

based on

history

Updated: June 2023

Page 1 of 15

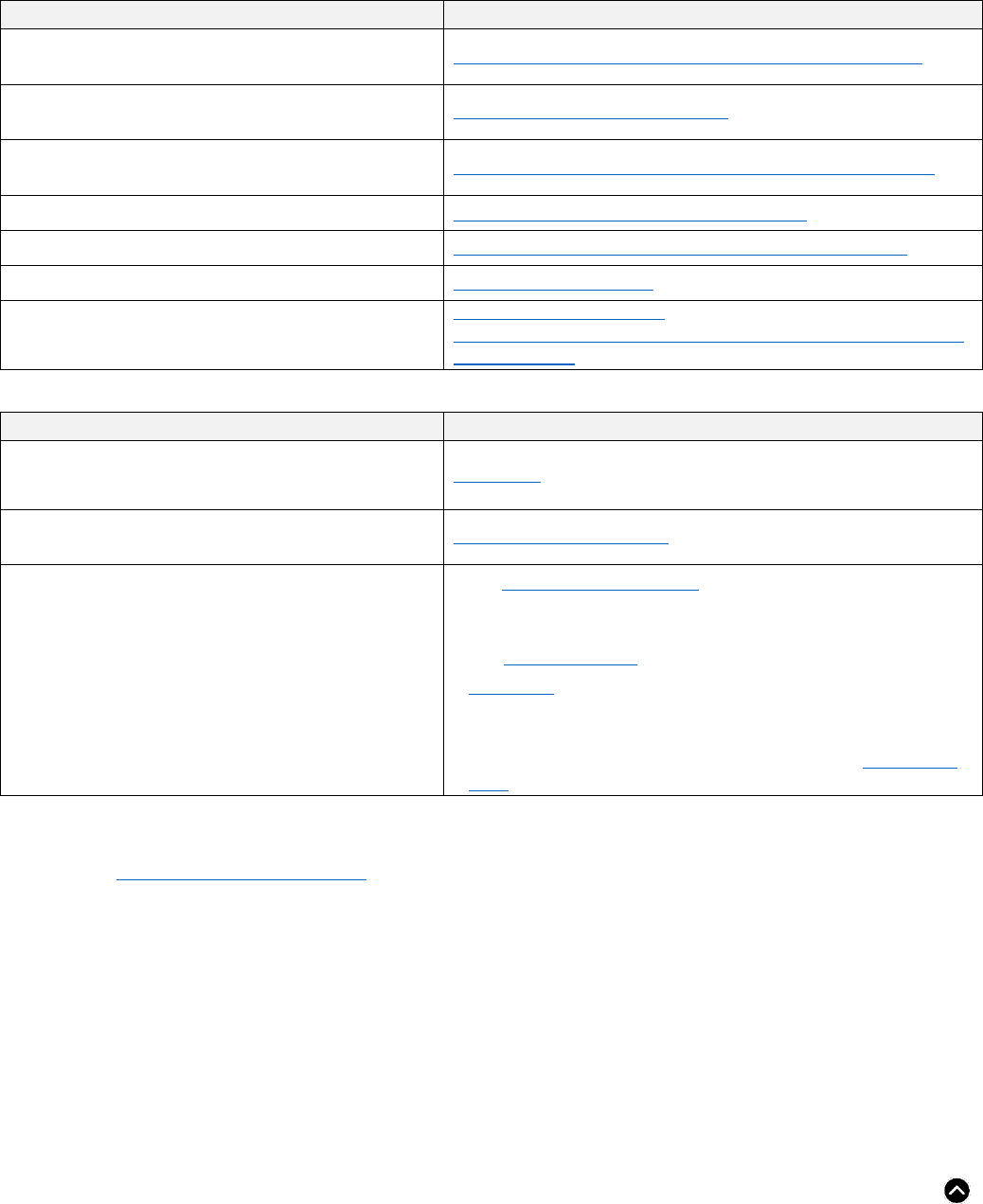

BackgroundProvider resources

Patient resources

Pre-referral checklist

Quick

links:

Expanded details

Advice options Patient pathway

Pathway primer

• 3 or more loose/watery stools per day

• Onset at least 4 weeks ago

1. Suspected chronic diarrhea

• Blood: CBC, electrolytes, ferritin, CRP, celiac disease screen

• Stool: C. difficile, ova and parasites

*If high clinical suspicion of IBD, do fecal calprotectin test (see Expanded Details)

• Medical history and physical examination

• Medication-induced diarrhea: optimize or discontinue use

• History of cholecystectomy

• Identify common triggers like sugar alcohols (mannitol, sorbitol), lactose, fructose, and gluten/wheat

• Microscopic colitis

• Irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea predominant (IBS-D)

• Bile acid induced diarrhea (BAD)

• Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

• Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI)

5. General principles for treatment and management of chronic diarrhea

• Education on normal stool form and bowel movement frequency

• Patient reassurance and management of expectations

• Modify diet, remove trigger foods, and space small meals throughout the day

• Soluble fibre supplementation and ensure adequate water intake

• Lifestyle modification: physical activity and psychological therapy (e.g. sleep disorder and stress management)

6. Pharmacological options for treating chronic diarrhea

• Anti-diarrheals/anti-motility agents (Loperamide, Diphenoxylate-atropine)

• Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA)

• Bile acid sequestrants

• Antibiotics (Rifaximin)

No

If fecal cal

test > 120

ug/g or

positive for

celiac

8. Refer for

consultation/

endoscopy

Treat or

refer for

consultation

Yes

If unsatisfactory

response, consider

using an advice

service before

referring

If IBS

suspected

Follow

IBS

pathway

Provide feedback

Provide Feedback ˃

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 2 of 15 Back to Algorithm

CHRONIC DIARRHEA PATHWAY PRIMER

• Chronic diarrhea is defined as 3 or more loose or watery stools/day (Type 6-7 on the Bristol Stool Chart)

often associated with an increase in frequency, but not always, and persisting for more than 4 weeks in

duration. Symptoms can also include an urgent need to pass stool and occasional incontinence, with

significant impact on the patient’s quality of life.

• This clinical pathway focuses only on the investigation and management of chronic diarrhea.

o Acute diarrhea is defined as 30 days or less. In Canada, acute diarrhea is most often infectious and

often requires only self-limited symptom management.

• Chronic diarrhea is common gastrointestinal disorder, affecting approximately 3-5% of the general

population.

1

• Chronic diarrhea is more common among women than men and those with a body mass index > 30.

• Challenges may exist distinguishing between chronic diarrhea and irritable bowel syndrome diarrhea-

predominant (IBS-D) as there is overlap in symptoms.

o Pathogenic mechanisms of chronic diarrhea may be common to that of IBS, including underlying

motility disruption.

o Chronic diarrhea is distinct from IBS-D as it occurs characteristically in the absence of abdominal

pain, thus visceral hypersensitivity is less of a feature.

Checklist to guide in-clinic review of your patient with Chronic Diarrhea

□

Confirm absence of alarm features (see algorithm Box 2).

If alarm features identified, refer for specialist consultation.

□

Assess Rome IV criteria for IBS – recurrent abdominal pain > 1 day per week in the last three months related to

defecation or associated with change of frequency and/or form (appearance) in stool.

If present, refer to the IBS pathway.

□

Complete baseline investigations confirming no abnormal results (CBC, electrolytes, ferritin, celiac disease

screen, and stool testing for C.difficile and ova and parasites).

□

Address other causes of diarrhea – medical conditions, culprit medications (see Table 1), alternative diagnoses,

and dietary triggers.

EXPANDED DETAILS

1. Suspected chronic diarrhea

A careful history will provide significant insight into the etiology of chronic diarrhea. There are two main categories to

consider:

• Functional causes

o Functional diarrhea without abdominal pain, not associated with inflammation or alteration to the

gastrointestinal tract. It is distinct from IBS-D and post-infectious IBS, which is classically

associated with pain/abdominal discomfort.

1

Scallan, E., Majowicz, S. E., Hall, G., Banerjee, A., Bowman, C. L., Daly, L., ... & Angulo, F. J. (2005). Prevalence of diarrhea in

the community in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United States. International journal of epidemiology, 34(2), 454-460.

This primary care pathway was co-developed by primary and specialty care and includes input from multidisciplinary

teams. It is intended to be used in conjunction with specialty advice services, when required, to support care within

the medical home. Wide adoption of primary care pathways can facilitate timely, evidence-based support to

physicians and their teams who care for patients with common low-risk GI conditions and improve appropriate

access to specialty care, when needed. To learn more about primary care pathways, check out this

short video.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 3 of 15 Back to Algorithm

• Organic causes

o Irritable bowel disease (IBD), celiac disease, microscopic colitis, medication-induced diarrhea, bile

acid induced diarrhea (BAD), or other rare causes of diarrhea (e.g., radiation induced).

Chronic diarrhea can also be described as one of, or a combination of, the following pathophysiologic processes:

• Watery Diarrhea:

o Osmotic

The amount of water present in the stool is dependent upon the presence of

solutes/effective osmoles (e.g., lactose, fructose).

The presence of poorly absorbed solutes (e.g., maldigested sugars) in the bowel inhibit

normal water and electrolyte absorption and may lead to diarrhea (presence of higher

water content in the stool).

Some laxatives (e.g., lactulose, citrate of magnesium) or foods/nutrients (e.g., lactose,

sorbitol, and fructose) may not be well absorbed, leading to osmotic diarrhea.

When the solute is removed (excluded from the diet), the diarrhea typically resolves.

o Secretory

Caused by excessive electrolyte secretions in the colon, leading to increased fluid.

One characteristic feature is the persistence of secretion during fasting/removal of food.

Medications (e.g., antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)), poorly reabsorbed bile acids

or fatty acids in the colon, and microscopic colitis are possible causes; and rarely,

hormone-producing tumors, excessive prostaglandin production, and other intestinal

diseases (e.g., IBD and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)).

• Inflammatory Diarrhea

o The presence of blood and mucous in the stool can occur from inflammation and this may be

immune-mediated. This occurs with chronic conditions, including IBD and other rare chronic

infections (e.g., amoebiasis, tuberculosis (TB)).

o Mucous can be a normal presence in stool and does not necessarily reflect inflammation. The key

difference is the presence of blood. This is a red flag and necessitates referral.

• Overflow Diarrhea

o A history of antecedent chronic constipation, particularly in the elderly, necessitates consideration

of overflow diarrhea as a source of new onset/ poorly controlled watery stools in this context.

o Plain x-ray imaging of the abdomen to identify fecal loading may be helpful to direct management

(see Chronic Constipation pathway).

Additional history:

• Medication review

o Many medications can cause chronic diarrhea, including over the counter medications (see Table 1).

• Travel history and associated illness (gastroenteritis)

o IBS associated with prior short-term, self-limited gastroenteritis is common and can lead to longer-

term altered bowel habit (post-infectious changes or IBS). This can occur in conjunction with pain

(see IBS pathway).

• Personal or significant family history of immune-mediated disease (e.g., thyroid disease, IBD, or celiac

disease).

• Diet

o A dietary review can be helpful to identify easily avoidable contributing factors, such as excessive

caffeine, dairy products (e.g., high lactose foods, like milk and ice cream), sugar sweetened

beverages, gluten/wheat, etc.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 4 of 15 Back to Algorithm

2. Alarm features

If any of the following alarm features are identified, refer for consultation/endoscopy. Include any and all identified

alarm features in the referral to ensure appropriate triage.

• Family history (first-degree relative) of IBD or colorectal cancer

• Onset of symptoms after age 50

• Unintended weight loss (> 5% over 6-12 months)

• Nocturnal symptoms or significant incontinence

• Visible blood in stool (see High Risk Rectal Bleeding Pathway and/or Iron Deficiency Anemia Pathway)

• Iron deficiency anemia (see Iron Primer)

Although alarm features are important to recognize, they have not been shown to be highly predictive of colon cancer.

3. Baseline investigations

• Blood

o CBC, electrolytes, ferritin

o C Reactive Protein (CRP): a non-specific marker of inflammation with modest accuracy for

detecting inflammation. The sensitivity or false negative rate is approximately 70-75% with

limitations as non-specific. If elevated, it can be helpful, but if normal, does not definitively exclude

an inflammatory condition. A very low CRP value is, however, reassuring.

2

o Celiac disease screen: a highly accurate (sensitivity is ~95%) antibody screen for this immune-

mediated condition. Ensure diet is gluten inclusive for at least two weeks prior to testing to ensure

no false negatives.

• Stool

o C. difficile, stool for ova and parasites

o In Alberta, the most common parasites are Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Entamoeba histolytica,

but others may be indicated if there has been travel history. If there is a relevant travel history or

other relevant factors, provide this information in the details of the ova and parasites requisition.

o Note: Tests such as stool leukocytes and fat globules are generally not recommended. Fecal

immunochemical testing (FIT) has NOT been validated for investigation of chronic diarrhea-like

symptoms. Ordering FIT in this circumstance is inappropriate given the presence of symptoms.

o Further investigation using fecal calprotectin - consider ordering a fecal calprotectin if there is a

high clinical suspicion of inflammation.

o Fecal calprotectin is a stool-based test used to detect a protein released into the gastrointestinal

tract from inflammatory cells (neutrophils) when present. Fecal calprotectin may be elevated and

useful when there is a high clinical suspicion of IBD.

o Elevated levels of fecal calprotectin are found in inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and

Ulcerative colitis). However, mid-range levels can also be found in several benign conditions, such

as in patients on NSAIDs or PPIs or those with GI infections, celiac disease, and microscopic colitis

(see Microscopic Colitis Primer). By contrast, in functional disorders such as IBS, fecal calprotectin

levels are normal.

3

• FCP methods are not standardized, so numerical FCP results tested by DynaLIFE should NOT be

compared to previous FCP results from the referral laboratory.

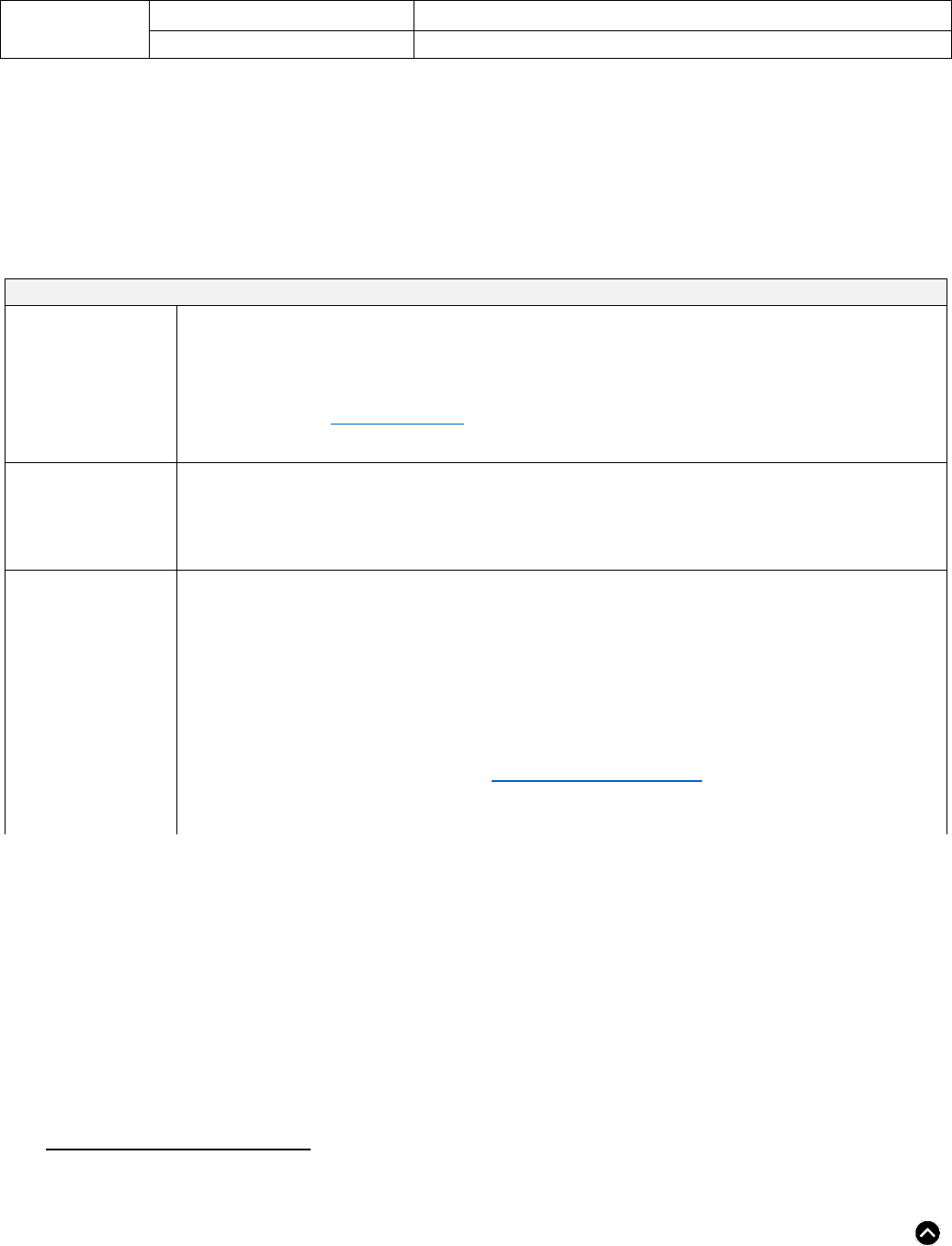

Indication for testing

Result

Interpretive Guidance

<50 µg/g

Normal (no detectable inflammation).

2

Menees, S. B., Powell, C., Kurlander, J., Goel, A., & Chey, W. D. (2015). A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein,

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with

IBS. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 110(3), 444-454.

3

York Teaching Hospital – NHS Foundation Trust & Yorkshire and Humber Academic Health Sciences Network (2016, July) The

York Faecal Calprotection Care Pathway Information for GPs. https://www.yorkhospitals.nhs.uk/seecmsfile/?id=941

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 5 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Investigation of patients with GI

symptoms*

50-120 µg/g

Indeterminate (If symptoms persist, consider repeating the test in

4-6 weeks).

>120 µg/g

Elevated (refer for specialist consultation or physician advice).

Monitoring of known IBD

patients

>250 µg/g

Result suggests active inflammation.

*For Patient <4 years of age

•

High levels of fecal calprotectin are commonly observed in pediatric patients less than 4 years of age. Robust pediatric reference

intervals have not been established for this age group.

4. Optimize management of secondary causes

• A detailed medical history and physical examination should be performed at presentation to assess for a

multitude of other conditions that mimic functional diarrhea.

• A careful review of medications should be performed to identify ones that may be causing GI side effects.

Some common medications include PPIs, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), NSAIDs, laxatives/antacids,

magnesium supplements, metformin, antidepressants, antigout agents, anti-hypertensives, and herbal

products (see Table 1).

o Optimization of underlying medical conditions, including diabetes and thyroid disorders

o Discontinue use or reduce dosage of culprit medications

• Ask about a history of cholecystectomy and whether this coincided with onset or worsening of symptoms.

Post-cholecystectomy diarrhea, due to BAD, can be treated with cholestyramine.

• Ask about a history of bariatric surgery and whether this coincided with onset or worsening of symptoms.

• Ask about history of COVID-19 infection.

• Assess common dietary triggers - excessive intake of sugar sweetened beverages, juice, alcohol, caffeine

(e.g., coffee, tea), artificial sweetener (e.g., sorbitol, diet pop), dairy (e.g., high lactose content in milk and ice

cream), and gluten/wheat.

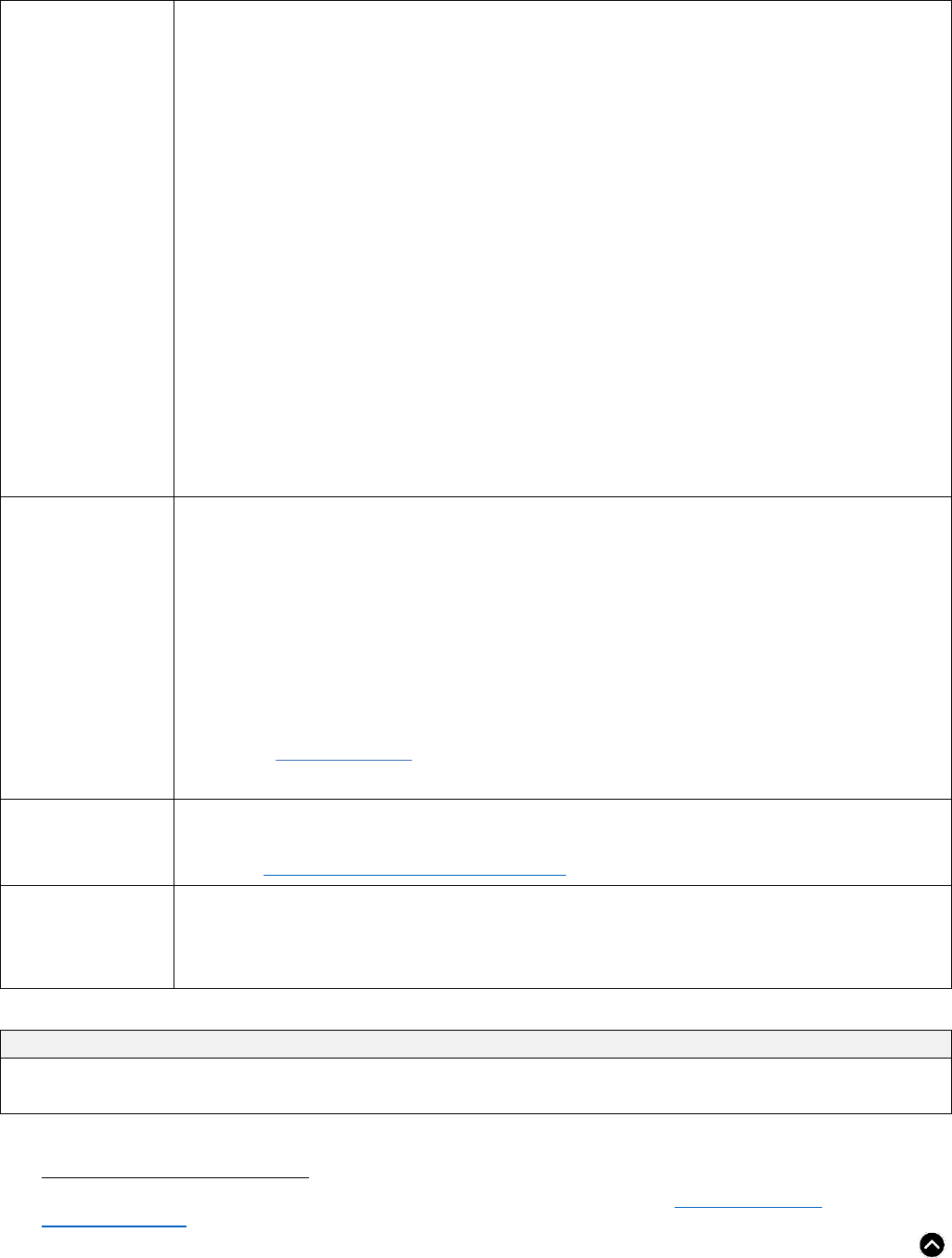

Table 1: Common medications that may cause diarrhea.

System

Class

Common culprits

Cardiovascular

Anti-platelets ASA

Antiarrhythmics digoxin, procainamide

Antihypertensives

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), angiotensin receptor

blocker (ARBs)*, beta-blockers

Cholesterol/lipid-lowering agents statins

Central nervous

system

Antidepressants selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs)

Anti-parkinsonian medications levodopa, pramipexole, entacapone

Others lithium

Endocrine

Oral hypoglycemic agents metformin, acarbose, GLP-1 receptor agonists

Thyroid replacement levothyroxine

Gastrointestinal

Anti-secretory agents / antacids proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), magnesium-containing antacids

Laxatives any

Other orlistat

Musculoskeletal

NSAIDs ASA, ibuprofen, naproxen

Gout therapy colchicine, allopurinol

Other

Antibiotics most**

Antineoplastic agents several

Immunosuppressants mycophenolate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, sirolimus

Vitamin supplements

vitamin C - doses over the upper limit of 2000 mg/day

magnesium - doses over the upper limit of elemental Mg 350 mg/day

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 6 of 15 Back to Algorithm

potassium chloride

Herbal supplements

*Olmesartan has been associated with sprue-like enteropathy

**Clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and 3

rd

-generation cephalosporins are common causes of C. difficile-associated diarrhea

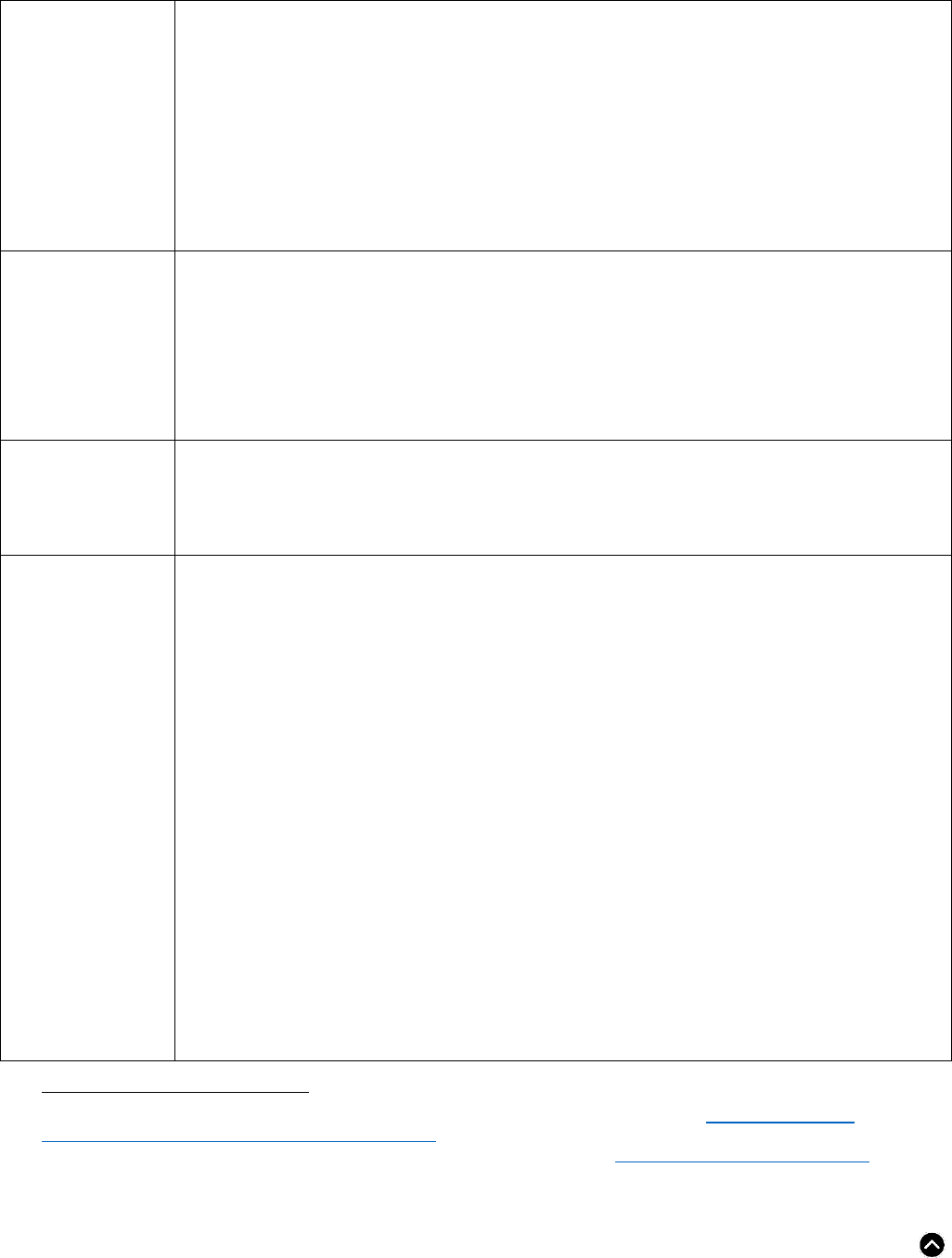

5. General principles for treatment and management of chronic diarrhea

Patients with functional bowel disorders will benefit from lifestyle and dietary modifications. These simple

modifications may be all that is required in those with mild or intermittent symptoms where quality of life is not

significantly impacted. Connecting patients with resources for diet, exercise, stress reduction, and psychological

counseling, where available, may be helpful. Initial assessment should include screening for underlying sleep and/or

mood disorders. Patients with mental health issues such as depression and anxiety may have refractory symptoms

unless mental health issues are addressed.

Treatment options (non-pharmacological)

Education on normal

stool form and bowel

movement frequency

• Details on variable frequency and form that is part of a normal spectrum of bowel habit.

• There is marked variation in what is considered a normal bowel habit. In a study of healthy

individuals, stool frequency varied from a low of 3 to a high of 21 bowel movements per week as

being in the normal range.

4

Similarly, there is some normal variation in stool consistency as

measured by the Bristol Stool Chart.

• If stool habit changes substantially, and persists, further investigations may be needed.

Patient reassurance

and management of

expectations

• A key to long-term, effective management is to provide patients reassurance after their initial

diagnosis and offer points of reassessment and reappraisal to establish a therapeutic relationship.

• Reassessment is recommended if there is a significant increase in diarrhea or signs and symptoms

of dehydration.

Modify diet, remove

trigger foods, and

space small meals

throughout the day

• Referral to a dietitian can be helpful.

• Eat smaller meals spaced over the day to reduce gastric load.

• Diets high in lactose, fructose, sugar sweetened beverages and juices, diet beverages, sugar free

gum, sorbitol, caffeine, and gluten/wheat can increase symptoms.

• Water is the best choice for hydration.

• Assess common food triggers. Follow a systematic approach of removing triggers and assessing

symptoms before permanent elimination.

• It may be helpful for patients to use the Bowel and Symptom Journal to understand their symptoms,

food triggers, and stressors. Use the diary to determine how dietary modifications, psychological,

and pharmacological therapies impact their symptoms.

4

Mitsuhashi, S., Ballou, S., Jiang, Z. G., Hirsch, W., Nee, J., Iturrino, J., ... & Lembo, A. (2018). Characterizing normal bowel

frequency and consistency in a representative sample of adults in the United States (NHANES). American Journal of

Gastroenterology, 113(1), 115-123.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 7 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Fibre and fluids

•

Total fibre: Adults are recommended to consume 14 g/1000 kcal of fibre per day. Suggest about

21-38 g/day for most adults.

• Two types of fibre:

o Insoluble fibre is found in wheat bran, the skin of fruits, and many raw vegetables. It adds bulk

to the stool and contributes greatly to daily total fibre requirements. It may not add therapeutic

health benefits like soluble fibre.

o Soluble fibre is found in psyllium, oats, barley, fruit, and seeds. It absorbs water in the intestine

to form a viscous gel that thickens the stool and stimulates peristalsis.

o There is a dose-response relationship between fibre plus fluid intake and stool output. This is

important to quantify, as patients whose fibre and fluid intake is inadequate are most likely to

benefit from this intervention. Fibre acts as a sponge, so it is important to combine fluid and

fibre. Increased fluid intake on its own will only result in increased urination.

• Soluble fibre supplementation:

o May provide symptom relief for patients with IBD, IBS, constipation, and diarrhea. The

therapeutic goal is 5-10 g/day of soluble fibre from foods and supplements including:

1 tbsp. psyllium husk or powder supplement - 3.0 grams

2 tbsp. ground flaxseed - 1.8 grams

½ cup kidney beans - 2.8 grams

1 pear - 2.2 grams

Fibre and fluids

cont’d

• General care:

o

Increasing fibre intake may result in negative side-effects that can be minimized or avoided.

Slowly increase fibre to prevent gas, abdominal pain, and bloating. Start with a third of a

dose and determine tolerance.

Drink additional fluid (water) to compliment a high fibre diet. Inadequate fluid may lead

to constipation, hardening of stool, bloating, and abdominal pain.

Caution soluble fibre intake for people with or at risk of a bowel obstruction or narrowing

of the esophagus, stomach, or intestine.

Fibre supplements may reduce or delay absorption of certain medications.

o See Patient Resources section for more information on fibre supplementation.

• Ensure adequate fluids: 2 L/day for females, 3 L/day for males

Physical activity

• 20+ minutes of physical activity/day, aiming for 150 min/week is known to be an effective strategy

for stress reduction.

• See the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines.

Psychological

therapy

• Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and hypnotherapy may help with stress management and

gastrointestinal symptoms.

5

It is recommended that therapy be provided by a regulated health

professional such as a registered psychologist.

• Screening for, and treating, any underlying sleep or mood disorders may be important.

6. Pharmacological options for treating chronic diarrhea

Treatment options (pharmacological)

The use of pharmaceuticals in functional bowel disorders is generally reserved for those who have not adequately responded

to dietary and lifestyle interventions, or in those with moderate or severe symptoms that impair quality of life.

5

DynaMed Plus. (2018, September 10). Confidence in Practice. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). https://www-dynamed-

com.ahs.idm.oclc.org/

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 8 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Loperamide

(Imodium

®

)

• Evidence: Effective for improved diarrheal symptoms but has not been shown to consistently

improve IBS-D symptoms.

• Mechanism of action: Through µ (mu) opioid receptor agonist, thus decreasing GI motility.

• Place in therapy: Effective antidiarrheal for prophylaxis for social situations or travel, however,

should not be prescribed for continuous use.

• Adverse effects: Sedation, nausea, abdominal cramps.

6

Lowest addiction potential of all opioids.

• Dose: 4 mg initially, followed by 2 mg after each loose bowel movement. Max 16 mg/day.

• Clinical improvement usually seen within 48 hours, if no clinical improvement after at least 10 days

on maximum dose, symptoms unlikely to be controlled by further administration.

7

Diphenoxylate -

Atropine (Lomotil

®

)

• Evidence: Adjunctive therapy in management of moderate to severe diarrhea.

• Mechanism of action: Through µ (mu) opioid receptor agonist, thus decreasing GI motility.

Atropine is an anticholinergic that further decreases GI motility and discourages abuse.

• Place in therapy: Less effective than loperamide but may be used for intermittent symptoms for

some patients.

• Adverse effects: Sedation, nausea, abdominal cramps, dry skin, and mucous membranes (from

atropine). Some addiction potential.

5

Diphenoxylate -

Atropine (Lomotil

®

)

cont’d

• Dose: 5 mg PO initially, then 2.5 mg PO after each loose bowel movement. Max 20 mg/day.

• The elderly are more susceptible to anticholinergic effects.

• Avoid concomitant use with monoamine oxidase inhibitors as this may precipitate hypertensive

crisis.

Tricyclic

antidepressants

(TCA)

• Evidence: The most studied antidepressant class for treatment of abdominal pain.

8

• Mechanism of action: Suggested to be beyond serotonin and norepinephrine, and because of

blocking voltage-gated ion channels, opioid receptor activation and potential neuro-immunologic

anti-inflammatory effects.

9

Their anticholinergic properties also slow GI transit time.

• Place in therapy: Recommended for overall symptom improvement in patients with IBS, as well

as sleep issues, anxiety, or depression.

• Adverse effects: Anticholinergic and antihistaminic (drowsiness/insomnia, xerostomia,

palpitations, weight gain, constipation, urinary retention).

9

• Use with caution in patients at risk of prolonged QT.

• It can take 2-3 months to reach maximum effect.

• The lowest effective dose should be used. Reassess therapy after 6-12 months.

• Dose should be gradually reduced if discontinuing.

Recommended Medications

• Nortriptyline - 10-25 mg qhs. Increase dose by 10-25 mg every 3-4 weeks (due to delayed onset).

May require 25-75 mg/day. Often takes 2-3 months for peak effect. ($20-60/month).

• Amitriptyline - 10-25 mg qhs. Increase dose by 10-25 mg every 3-4 weeks (due to delayed onset).

May require 25-75 mg/day. Often takes 2-3 months for peak effect. ($15-20/month).

• Desipramine - 25 mg qhs, increase based on response and tolerability. Doses up to 150 mg daily

have been evaluated for IBS (~$25/month).

6

DynaMed. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). EBSCO Information Services. Accessed June 10, 2021. https://www-dynamed-

com.ahs.idm.oclc.org/condition/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

7

DynaMed. Chronic Diarrhea. EBSCO Information Services. Accessed June 15, 2021. Chronic Diarrhea - DynaMed (oclc.org)

8

Törnblom, H., & Drossman, D. A. (2016). Centrally targeted pharmacotherapy for chronic abdominal pain: understanding and

management. Gastrointestinal Pharmacology, 417-440.

9

Lexicomp, Inc., Lexi-Drugs Online, Hudson, Ohio: UpToDate, Inc; 2013; [cited 27 Apr 2021].

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 9 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Bile acid

sequestrants

• Evidence: An empiric trial may be considered for suspected bile acid induced diarrhea (BAD). May

result in significant clinical improvement in approximately 25% of people. Binds and removes bile

acids in the intestine.

• Mechanism of action: Through the formation of a non-absorbable complex with bile acids in the

intestine.

• Place in therapy: Use gradual daily dose titration to minimize adverse effects and use at the

lowest dose needed to minimize symptoms for BAD.

5

• Adverse effects: Nausea, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency with long-term use, constipation.

• Take other medications 1 hour before or 4-6 hours after.

• Dose: A 2–4-week titration trial is reasonable to see effects. Intermittent, on-demand use may also

be trialed.

• Relief usually occurs within 3 days of initiation of therapy. If no relief occurs, alternative therapy

should be initiated.

5

Recommended Medications

• Cholestyramine resin - 4 g PO Q12H, take with fluids. ($30/month). Pouch can be divided into a

smaller dose and mixed with water or juice (tomato or orange juice) starting at 2-4 g once/day,

titrating to effect.

• Colestipol (Colestid

®

) or Colesevelam (Lodalis

®

) available as tablets if patient is unable to tolerate

powder.

Second line therapies

Consider consulting a GI using Specialist Link, Connect MD, or e-Referral Advice Request for guidance on these treatments.

Rifaximin (Zaxine

®

)

• A non-systemically absorbed antibiotic.

• Mechanism of action: Not clearly identified, but may alter the microbiome, thus reducing gas

production.

• Dose: 550 mg 3x/daily for 2 weeks. This is a safe medication but tends to require multiple recurrent

courses. There is no long-term safety or efficacy data over 3 courses. (~$325 month, not covered by

public insurers).

7. Consider alternative diagnoses

• Microscopic Colitis (see Microscopic Colitis Primer)

• Irritable Bowel Syndrome-diarrhea predominant (IBS-D)

IBS is a brain-gut disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain/discomfort and altered bowel habits

(constipation, diarrhea, or both). It is often associated with bloating or abdominal distention. These key

symptoms can vary in severity and tend to remit and recur, often affected by dietary exposures and stress.

For patients with suspected IBS-D, the Rome IV diagnostic criteria may provide a guide.

Recurrent abdominal pain, on average, ≥ 1 day per week in the last 3 months, associated with ≥ 2 of the

following criteria where pain is:

o Related to defecation

o Associated with a change in frequency of stool

o Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

o Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis.

If the patient assessment identifies predominant symptoms of pain and/or bloating, refer to the IBS pathway.

• Bile acid induced diarrhea (BAD)

Bile acids produced in the liver and stored in the gallbladder are normally secreted into the small bowel in

response to a meal, and then reabsorbed in the distal ileum (also known as enterohepatic circulation). Bile

acid overproduction or poor/ ineffective ileal reabsorption (bile acid malabsorption/ bile acid diarrhea or

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 10 of 15 Back to Algorithm

BAM/BAD) can dysregulate this process. Subsequent unabsorbed bile acids stimulate sodium and water

secretion in the colon, increase motility, and stimulate defecation, thereby contributing to chronic diarrhea.

10

There are several subtypes:

o Idiopathic: contributing to 25-35% of patients with chronic diarrhea-predominant IBS-D or chronic

functional diarrhea

o Post-cholecystectomy

o Other: secondary to small bowel resection (Crohn’s disease) or radiation therapy affecting the

ileum

Diagnosis and treatment:

Diagnosis may be challenging. Giving an empiric trial of bile acid sequestrants is reasonable, easy, and

inexpensive. See Treatment options - Bile acid sequestrants.

• Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Unlike the colon, a significant number of bacteria do not normally reside in the small bowel. Small intestinal

bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition where dysbiosis or increased bacteria are present proximal to the

ileocecal valve and within the small bowel where there is normally less bacteria. SIBO is a rare cause of

gastrointestinal symptoms.

SIBO should only be considered in patients who have:

11

o Severe diabetic neuropathy

o Advanced scleroderma

o Anatomic alterations such as surgery for Crohn’s disease, Crohn’s strictures, and/or radiation

o Immune deficiency (e.g., common variable immunodeficiency)

o Note: The accuracy of the breath test for SIBO is highly variable and may be unreliable. Routine

testing for SIBO is not currently recommended.

12,13

o The use of hydrogen breath testing has been used in the past to make a diagnosis of SIBO.

However, the accuracy is not consistent, therefore; should not be ordered in primary care.

Empiric antibiotic treatment for SIBO should only be considered for symptomatic patients with at least one of

the above considered risk factors. See Second line therapies - Rifaximin.

• Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI)

The normal functioning pancreas produces enzymes responsible for facilitating macronutrient digestion

(enzymatic cleavage) so absorption can occur. Pancreatic insufficiency is not a common cause of chronic

diarrhea but may be a contributing component in the context of known pancreatic disease (e.g., chronic

pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, or prior surgical resection of the small bowel or stomach). If you suspect

pancreatic insufficiency in someone with pancreatic disease, consider testing stool for fecal elastase (low

levels suggest pancreatic insufficiency). Routine use of pancreatic enzymes to support digestion are not

supported by evidence and are costly.

8. When to refer for consultation and/or endoscopy

• If alarm features are identified

• If investigation reveals a positive celiac disease screen

• If the fecal calprotectin result is > 120 µg/g

10

Sadowski, D. C., Camilleri, M., Chey, W. D., Leontiadis, G. I., Marshall, J. K., Shaffer, E. A., ... & Walters, J. R. (2020). Canadian

association of gastroenterology clinical practice guideline on the management of bile acid diarrhea. Journal of the Canadian

Association of Gastroenterology, 3(1), e10-e27.

11

Bull-Henry, K. (2020). Continuing Medical Education Questions: February 2020: ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial

Overgrowth. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(2), 164.

12

Farmer, A. D., Wood, E., & Ruffle, J. K. (2020). An approach to the care of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. CMAJ, 192(11),

E275-E282.

13

Shah, A., Talley, N. J., Jones, M., Kendall, B. J., Koloski, N., Walker, M. M., ... & Holtmann, G. J. (2020). Small intestinal bacterial

overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. American Journal of

Gastroenterology, 115(2), 190-201.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 11 of 15 Back to Algorithm

• If recommended strategies have led to unsatisfactory treatment or management of symptoms

o Note: Consider using an advice service before referring

• Colonoscopy may be helpful in patients with chronic diarrhea who have persistent symptoms or limited

benefit from usual treatments.

o The purpose of endoscopic examination is to exclude chronic immune-mediated conditions

including Crohn’s disease and microscopic colitis.

o Note: Microscopic colitis is generally a benign condition that is most often treated with anti-

diarrheal or binding agents).

• Provide as much information as possible on the referral form, including identified alarm feature(s), important

findings, and treatment/management strategies trialed with the patient.

Still concerned about your patient?

The primary care physician is typically the provider who is most familiar with their patient’s overall health and knows

how they tend to present. Changes in normal patterns, or onset of new or worrisome symptoms, may raise suspicion

for a potentially serious diagnosis, even when investigations are normal and typical alarm features are not present.

There is evidence to support the importance of the family physician’s intuition or “gut feeling” about patient symptoms,

especially when the family physician is worried about a sinister cause such as cancer. A meta-analysis examining the

predictive value of gut feelings showed that the odds of a patient being diagnosed with cancer, if a GP recorded a gut

feeling, were 4.24 times higher than when no gut feeling was recorded.

14

When a “gut feeling” persists despite normal investigations, and you decide to refer your patient for specialist

consultation, document your concerns on the referral with as much detail as possible. Another option is to seek

specialist advice (see Advice Options) to convey your concerns.

PRIMERS

Iron Primer

Evaluation of measures of iron storage can be challenging. Gastrointestinal (occult) blood loss is a common cause of

iron deficiency and should be considered as a cause when iron deficiency anemia is present. Menstrual losses

should also be considered.

There are two serological tests to best evaluate iron stores (ferritin, transferrin saturation) - neither of which are

perfect.

The first step is to evaluate ferritin:

• If the ferritin is below the lower limit of normal (lower limit of normal is 30 µg/L for men and 20 µg/L for

women), it is diagnostic of iron deficiency with high specificity (98% specificity).

• Ferritin is an acute phase reactant which may be elevated in the context of acute inflammation and infection.

If ferritin is normal or increased, and you suspect it may be acting as an acute phase reactant, order a

transferrin saturation test (see below).

o However, if the ferritin is > 100 µg/L and there is no concurrent significant chronic renal

insufficiency, iron deficiency is very unlikely - even in the context of acute inflammation/infection.

The second step is to evaluate transferrin saturation:

• The transferrin saturation is a calculated ratio using serum iron and total iron binding capacity. Serum iron

alone does not reflect iron stores.

• Low values (< 16%) demonstrate low iron stores in conjunction with a ferritin < 100 µg/L.

In the absence of abnormal iron indices, anemia may be from other causes other than GI (occult) blood loss (e.g.,

bone marrow sources, thalassemia, and sickle cell anemia).

14

Friedemann Smith, C., Drew, S., Ziebland, S., & Nicholson, B. D. (2020). Understanding the role of General Practitioners’ gut

feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. British Journal of General

Practice, 70(698), e612-e621.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 12 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Microscopic Colitis Primer

Microscopic colitis is a benign condition with a median age of onset in the mid-60s, more often in women than men. It

is characterized by non-bloody, watery/secretory diarrhea having significant potential impact on quality of life. Atypical

presentations can also occur.

• Examination by colonoscopy reveals normal findings, inflammation is present only histologically (on biopsy).

• Medications have been implicated in the pathophysiology. Common offenders include NSAIDs, proton pump

inhibitors (PPIs), statins, topiramate, and SSRIs. Consideration should be given to stopping these

medications, if possible.

• This condition is non-progressive, and therapy is directed to improving quality of life and stool habit

regularity (< 3 stools per day, minimal water content).

• Treatment for microscopic colitis is similar to those used in the treatment of IBS.

o Increased soluble fibre (psyllium, inulin) can be helpful to regular stool habit in addition to

loperamide, as needed.

o For more significant manifestations (defecation at night, incontinence), corticosteroid therapy may

be indicated (e.g., budesonide/Entocort

®

or Cortiment

®

(little to no evidence exists for prednisone).

• Total treatment duration ranges on response from 6-8 weeks to 12 weeks.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 13 of 15 Back to Algorithm

Provide Feedback ˃

BACKGROUND

About this Pathway

•

Digestive health primary care pathways were originally developed in 2015 as part of the Calgary Zone’s

Specialist LINK initiative. They were co-developed by the Department of Gastroenterology and the Calgary

Zone’s specialty integration group, which includes medical leadership and staff from Calgary and area

Primary Care Networks, the Department of Family Medicine, and Alberta Health Services.

•

The pathways were intended provide evidence-based guidance to support primary care providers in caring

for patients with common digestive health conditions within the medical home.

•

Based on the successful adoption of the primary care pathways within the Calgary Zone, and their impact on

timely access to quality care, in 2017 the Digestive Health Strategic Clinical Network led an initiative to

validate the applicability of the pathways for Alberta and to spread availability and foster adoption of the

pathways across the province.

Authors & Conflict of Interest Declaration

This pathway was reviewed and revised under the auspices of the Digestive Health Strategic Clinical Network in

2021, by a multi-disciplinary team led by family physicians and gastroenterologists. Names of participating reviewers

and their conflict-of-interest declarations are available on request.

Pathway Feedback and Review Process

Primary care pathways undergo scheduled review every three years, or earlier if there is a clinically significant

change in knowledge or practice. The next scheduled review is May 2024; however, we welcome feedback at any

time. Click on the Provide Feedback button to provide your feedback.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

You are free to copy, distribute, and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to

Alberta Health Services and Primary Care Networks and abide by the other license terms. If you alter, transform, or

build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar, or compatible license. The

license does not apply to content for which the Alberta Health Services is not the copyright owner.

Disclaimer

This pathway represents evidence-based best practice but does not override the individual responsibility of health

care professionals to make decisions appropriate to their patients using their own clinical judgment given their

patients’ specific clinical conditions, in consultation with patients/alternate decision makers. The pathway is not a

substitute for clinical judgment or advice of a qualified health care professional. It is expected that all users will seek

advice of other appropriately qualified and regulated health care providers with any issues transcending their specific

knowledge, scope of regulated practice or professional competence.

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 14 of 15 Back to Algorithm

PROVIDER RESOURCES

Advice Options

Non-urgent advice is available to support family physicians.

• Gastroenterology advice is available across the province via Alberta Netcare eReferral Advice Request

(responses are received within five calendar days). View the Referring Provider – FAQ document for more

information.

• Non-urgent telephone advice connects family physicians and specialists in real time via a tele-advice line.

Family physicians can request non-urgent advice from a gastroenterologist:

o In the Calgary Zone at specialistlink.ca or by calling 403-910-2551. This service is available from

8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Monday to Friday (excluding statutory holidays). Calls are returned within

one (1) hour.

o In the Edmonton and North Zones by calling 1-844-633-2263 or visiting pcnconnectmd.com. This

service is available from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Monday to Thursday and from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00

p.m. Friday (excluding statutory holidays and Christmas break). Calls are returned within two (2)

business days.

References

Ma, C., Battat, R., Parker, C. E., Khanna, R., Jairath, V., & Feagan, B. G. (2019). Update on C-reactive protein and fecal

calprotectin: are they accurate measures of disease activity in Crohn’s disease? Expert review of gastroenterology &

hepatology, 13(4), 319-330.

Resources

Poverty: A Clinical Tool for Primary Care Providers (AB)

cep.health/media/uploaded/Poverty_flowAB-2016-Oct-28.pdf

Nutrition Guideline: Household Food Insecurity

ahs.ca/assets/info/nutrition/if-nfs-ng-household-food-

insecurity.pdf

Last Updated: June 2023 Page 15 of 15 Back to Algorithm

PATIENT RESOURCES

Information

Description

Website

General information on diarrhea

(MyHealth.Alberta.ca)

myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?Hwid=diar4

General information on diarrhea

(Canadian Digestive Health Foundation)

cdhf.ca/digestive-disorders/diarrhea/

Diarrhea and Diet

(GI Society & Canadian Society of Intestinal Research)

badgut.org/information-centre/health-nutrition/diarrhea-and-diet/

Fibre Facts

ahs.ca/assets/info/nutrition/if-nfs-fibre-facts.pdf

Bowel and Symptom Journal

ahs.ca/assets/info/nutrition/if-nfs-bowel-symptom-journal.pdf

Nutrition Education Material

ahs.ca/NutritionResources

Gut Health Patient Journal

(Physician Learning Program)

9c849905-3a37-465a-9612-

7db1b9a0a69c.filesusr.com/ugd/7b74c1_81f1695f08214a66bc3394

62c52cd011.pdf

Services Available

Description Website

Services for patients to prevent or to manage chronic

conditions

(Alberta Healthy Living Program - AHS)

ahs.ca/ahlp

Supports for working towards healthy lifestyle goals and

weight management (Weight Management – AHS)

ahs.ca/info/Page15163.aspx

Referral to a Registered Dietitian

• Visit Alberta Referral Directory and search for nutrition

counselling.

• To learn more about programs and services offered in your zone,

visit Nutrition Services.

• Health Link has Registered Dietitians available to answer nutrition

questions. If a patient has nutrition-related questions, they can call

8-1-1 and ask to talk to a Dietitian.

• Patients can also complete the Health Link Dietitian Self-Referral

Form.

PATIENT PATHWAY

• Chronic diarrhea patient pathway